How We All Turned Japanese, a Tale of Global Hubris

The BOJ’s radical monetary policy is marking its 20-year anniversary. Raise a glass to the experiment the world replicated.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Marking the 20th anniversary of zero interest rates in Japan ought to be an exercise in humility.

Like the eldest child of a large family, the Bank of Japan was on its own for a while. Those that followed — the Federal Reserve and European Central Bank, to name but two — had it a bit easier. Some policy makers have acknowledged being too hard on Japan during its solo run. Former Fed chairman Ben Bernanke came away from his turn in the barrel more sympathetic.

Reviewing Japan’s experience at the Brookings Institution in 2017, Bernanke graciously conceded he once thought the BOJ was too timid and, in retrospect, he was far too certain about what could be accomplished with rock-bottom borrowing costs.

“When I found myself in the role of Fed chairman, confronted by the heavy responsibilities and uncertainties that came with that office, I regretted the tone of some of my earlier comments ... At a 2011 press conference, in response to a question from a Japanese reporter about my earlier views, I responded, ‘I’m a little bit more sympathetic to central bankers now than I was ten years ago.’”

Nicely put. Japan’s anniversary on Feb. 12 is time for everyone to reflect.

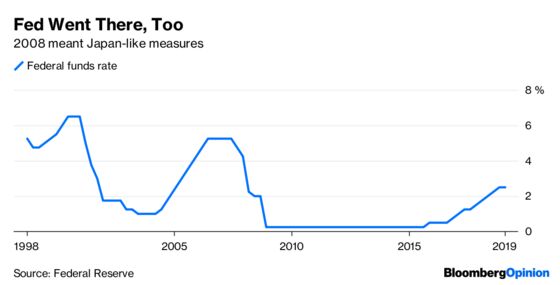

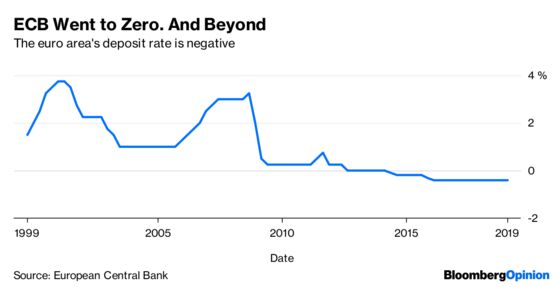

What began as a distinctly Japanese response to the aftermath of a property bust has gone mainstream in the two decades since February 1999. Major central banks have been forced into actions that resemble or go beyond Japan’s path. (Thank the global financial crisis and the euro emergency.) Zero rates and other one-time oddities like negative rates — the counterintuitive idea of borrowers getting paid and savers dinged — and massive bond buying, known as quantitative easing, are now legit.

Several lessons emerge. Zero rates may be necessary but not sufficient to tackle deflation or a severe economic slump. The practice also works best when joined with fiscal activism — as Bernanke recommended — and efforts to shore up banks. The approach could be deployed to combat the next recession, whenever it comes, or the next deflationary scare. With inflation retreating in the world’s major economies, that’s not a purely academic issue.

The secondary theme of this 20-year story is the incomplete perception of Japan. The country’s challenges tend to be conflated with stasis, which is a mistake. Within the decades bracketed by this anniversary, policy dialed up and down. In 2000, the BOJ raised its benchmark rate, an unforced error that had to be unwound when the world entered a slowdown early the following year. Quantitative easing ensued.

Arguably, Japan didn’t get really aggressive and bold until 2013. In a few short months, the inflation target was set at 2 percent; the recently elected Prime Minister Shinzo Abe appointed Haruhiko Kuroda as BOJ governor; and the new central bank chief embarked on a dramatic program of fresh stimulus.

Kuroda later took rates negative, though not as negative as the ECB, expanded the use of forward guidance and even talked about exceeding the inflation target for a while. He had some success. Consumer-price increases were on their way to 2 percent, before suffering a setback when a 2014 boost in Japan’s consumption tax resulted in recession.

While inflation hasn’t reached the 2 percent target, it’s (for now) a problem of low inflation, not deflation.

Japan’s economic run the past few years has been pretty good. True, inflation is now going the wrong way from 2 percent and the BOJ got some stick last week for trimming its projections. But inflation is below target in most large economies. It’s a difference of degree, not of kind.

For this commemoration, if you can call it that, the toasts might be to concepts rather than individuals. Like monetary-policy innovation and a recognition that the largest economies are more alike than different.

And the retirement of no small amount of hubris. See you in 20 years!

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rachel Rosenthal at rrosenthal21@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Daniel Moss is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian economies. Previously he was executive editor of Bloomberg News for global economics, and has led teams in Asia, Europe and North America.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.