The Big Minus at the Heart of OPEC-Plus

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- “OPEC+” is now the accepted nomenclature of the cobbled-together club of oil producers that has been trying to bolster prices since late 2016. As a brand, it has the advantages of a certain familiarity, expansiveness and positivity. It also rather oversells the product.

Monday’s meeting of the OPEC bit of things ran very late (the pluses are due to meet Tuesday). This is notable for two reasons. First, the delay reportedly stemmed largely from haggling among delegates about a proposed OPEC+ charter to enshrine cooperation among them. Second, the most salient decision, about whether or not to extend supply cuts, had been taken already by Saudi Arabia and Russia at the weekend’s G-20 gathering in Japan.

Once Prince Mohammed Bin Salman and President Vladimir Putin – representing almost half the group’s output between them – had agreed on extending supply cuts, the wider meeting was just a formality. Having everyone schlep to Austria anyway does help with oil demand, one supposes. But there’s something inescapably farcical about a meeting convened after the main decision has been publicized, but which then runs late because the delegates can’t agree on a declaration of harmony.

The second iteration of the OPEC+ supply cuts, which got underway in January, called on 21 countries – including 10 OPEC members – to keep about 1.2 million barrels a day off the market. Iran, Libya, and Venezuela – beset by sanctions, civil conflict and economic collapse, respectively – are exempt. When you look at the actual breakdown of cuts since then, however, it reinforces the sense that the group’s meetings are more theater than anything else at this point.

Consider that half the members subject to the agreement are tasked with the equivalent of a cover-charge to get into the club: cutting output by just 20,000 barrels a day or less. Having more countries sign up no doubt makes for a better group photograph. But the idea that anyone is actually tracking South Sudan’s compliance with its commitment to keep all of 3,000 barrels a day offline tends to detract from the vaunted seriousness of the operation. (Reader, South Sudan isn’t complying.)

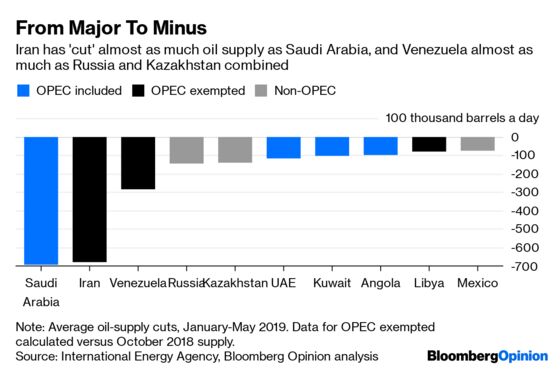

The group as a whole has done better, keeping an average of 1.33 million barrels a day off the market through May, for compliance of 111%. But the burden falls very unevenly. Saudi Arabia accounts for more than half the total barrels withheld, with compliance of 216%. Trusted partner Russia, on the other hand, has met only 64% of its (smaller) pledge – and even that’s partly due to contamination problems on a major pipeline.

But it’s the exempted countries – OPEC-minus? – that really show up the whole project.

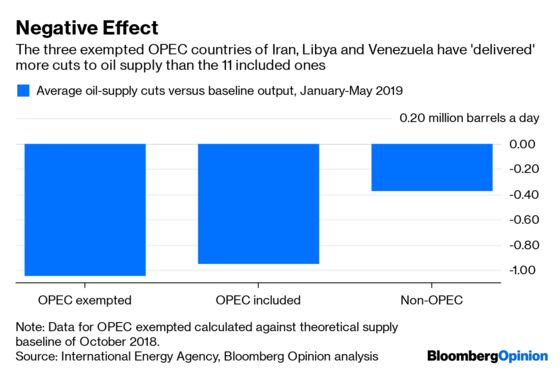

No quotas are enforced for Iran, Libya and Venezuela, of course. But taking 3% off their October 2018 output – which is roughly how the others were set – provides a proxy for what they might have been expected to contribute. On that basis, these three really punch above their weight:

OPEC-minus seriously ‘overcomplied’ with its theoretical cuts, at more than 600% in aggregate. Including these three countries, adjusted supply “cuts” add up to about 2.4 million barrels a day through the first five months of the year. The top 10 countries account for all of that and more, given non-compliance by others.

This represents continuity of sorts. During the first phase of the OPEC+ agreement, spanning 2017 and 2018, involuntary cuts arising from Venezuela's collapse were vital to the project’s success (so to speak).

This outsize role for the chronically afflicted reinforces the sense that even if OPEC isn’t quite dead, it isn’t quite living either. Yes, there are meetings, communiques, officials, a website, printed stationery and all the rest of it. But the actual task of managing supply has become the preserve of a relative few concentrated on the Arabian peninsula, aided by an ad hoc group of the walking wounded – including an arch adversary of those Arab states – and lent a veneer of credibility by a mercurial non-member, Russia. It was the latter, notably, that announced the pre-agreement on extending cuts, not Saudi Arabia.

The very fact that OPEC has tried to rope in ever more pledgers and shows so much deference to Moscow demonstrates its inherent weaknesses. The biggest of these is the sheer overweening dependence of many of its members on their favorite commodity. This makes them all fragile in an oil market that has become more competitive – especially as U.S. shale supply surges on the back of any price increases – and is subject to building constraints on demand.

Khalid Al-Falih, Saudi Arabia’s energy minister, confirmed at the eventual OPEC press conference that the group is now targeting its efforts at reducing global oil inventories to the average level of 2010-14. This makes sense on one level, given bloated inventories skewed the average after 2014. But with demand having risen by about 10% versus average demand in that period, OPEC’s new target represents a more aggressive approach. Al-Falih added, in response to a question, that he is essentially waiting out the shale boom in expectation of it eventually peaking and declining. In other words, he’s committed.

Despite such language, the supply cuts themselves and rising geopolitical tension, the recent rally in Brent crude since mid-June took it back only to where it traded in late May. Then Monday morning’s initial rally gave way as the OPEC meeting segued from foregone conclusion to … incredibly delayed foregone conclusion. The market remains unimpressed.

The big problem here is that ongoing pledges to cut supply are ultimately a sign of weakness in the oil market, not strength. So while formalizing them with an OPEC+ charter is intended to signal ongoing support, it cannot help but raise the question of why such extraordinary measures are now needed on a permanent basis. At this point, pluses not only don’t outweigh the minuses, they positively reinforce them.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Mark Gongloff at mgongloff1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.