(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Berlin, home to one of the world’s most regulated housing markets with formidable tenant protections, is considering an even more radical step: nationalization.

On Saturday, signature collection begins for a citywide referendum in the German capital on whether to nationalize the residential properties owned by big landlords. The top target, Deutsche Wohnen, is one of Europe’s largest property companies with 116,000 units in Berlin.

The initiators of the “Expropriate Deutsche Wohnen & Co.” are relying on Article 15 of the German Constitution, which has never been applied. It states that “land, natural resources and means of production” may be transferred to public ownership “for the purpose of socialization” provided adequate compensation is paid to the owners. The activists argue that the big landlords are driving up rents and, because of their market power – “big rental sharks serve as an example to big rental sharks” – making housing unaffordable for ordinary Berliners.

The nationalization movement started last year, when residents of 680 rented apartments on Karl Marx Allee learned their flats would be sold to Deutsche Wohnen. Karl Marx Allee is a major avenue in Berlin’s east that looks a lot like the street on which I lived in Moscow: An imposing row of post-World War II Stalinist Baroque buildings. It’s central and attractive, and the residents got word that Deutsche Wohnen would try to force them out despite Berlin’s strong rent-stabilization programs and tenant-protection laws that make it extremely difficult to kick out a tenant who isn’t in arrears. A rented-out apartment can sell for about 30 percent less than one without a lease.

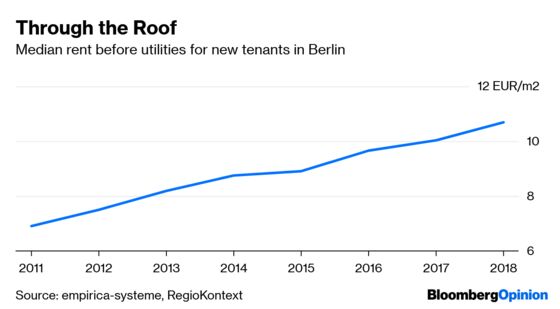

The Karl Marx Allee tenants held rallies and hung posters outside their windows. The highly visible campaign elicited sympathy in the city, where 85 percent of residents rent their dwelling and where the median asking rent for new tenants has gone up by 54 percent since 2011.

Besides, Deutsche Wohnen is unpopular: It has sharp lawyers who scrutinize rental contracts and pounce on loopholes.

Deutsche Wohnen denies that it’s trying to kick tenants out. On the 2018 earnings call on March 26, Chief Financial Officer Philip Grosse pointed out that while rents for the company’s Berlin properties increased 3.6 percent in 2018, existing tenants only saw 1.4 percent increases. “That is even below inflation rate, and in my view it shows how irrational the political debate has become in Germany these days,” Grosse said, pointing out that the average Berlin tenant spends just 22 percent of the net disposable household income on rent – lower than in many major cities.

Raising rents isn’t how Deutsche Wohnen really makes money. Last year, the company would have recorded a loss had it not added to its bottom line 2.6 billion euro ($2.9 billion) from marking the value of its properties to market. In a market as hot as Berlin’s it makes sense to buy properties for the revaluation profits rather than enduring the painful experience of squeezing out well-protected tenants to get an extra 2 percentage points’ rent out of an apartment.

As for market power, Deutsche Wohnen, with 6.8 percent of the rental apartments in Berlin, is hardly a dominant force. It argues that the real reason rents are rising so fast is that the city is rapidly filling with new residents (it added 20,600 people in 2018) and not building enough housing because of tougher permitting practices under the leftist city government.

Try telling that to Berliners. The left-wing, still relatively poor city-state, with higher unemployment than in most of Germany and where the government-owned railroad monopoly is the biggest employer, is bent on justice. Besides, Berlin residents have seen what gentrification has done to other European capitals, washing out their identities and replacing downtown populations. That’s what Berliners want to avoid – and they have plenty of experience fighting landlords and developers. The vast, empty Tempelhof airfield, a territory bigger than Monaco close to the city center, is testament to local residents’ power: In 2014, Berliners voted in a referendum to prevent construction there.

A referendum on “expropriating Deutsche Wohnen & Co” requires 20,000 signatures to start the process and then about 170,000 signatures to send the whole city to the polls. But it’s likely to happen, not least because Die Linke, the far-left party that’s part of Berlin’s governing coalition, is the strongest political force in the eastern part of the city.

The city government has already set an example with a program to keep the buildings on Karl Marx Allee out of Deutsche Wohnen’s hands. It relies on a seldom-used law that gives the city the right of first refusal on housing in areas with fast-growing rents.

Whether or not the referendum goes ahead, the city plans to buy back many of the apartment blocks it earlier sold to private owners. Berlin’s Social Democrat mayor, Michael Mueller, calls the privatizations a “mistake” but cautions against the use of the term “expropriation”: The buybacks cost Berlin hundreds of millions of euros. A referendum outcome requiring the authorities to increase the purchases to kick out the big landlords could have financially prohibitive consequences.

As a Berlin taxpayer, I feel uneasy about the plans. The relative affordability of rents helps make the city one of Europe’s most colorful, artistic and free-spirited capitals. But I can’t help but wonder why, if the city has the funds for nationalizations, it can’t use its money and regulatory powers to step up construction, especially in the former Communist east with its wide-open spaces or in spots now occupied by disused brutalist buildings. Trying to cap rents doesn’t just help existing tenants, it also encourages more newcomers to try their luck in the city, braving huge crowds at every apartment viewing – and, given the city’s stinginess with construction permits, there’s more and more pressure on the existing housing stock.

Socialist methods like nationalization can help for a while, but the authorities have no way of sealing a growing city. Berlin will need to look for better long-term solutions than the ones activists are pushing now.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Max Berley at mberley@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.