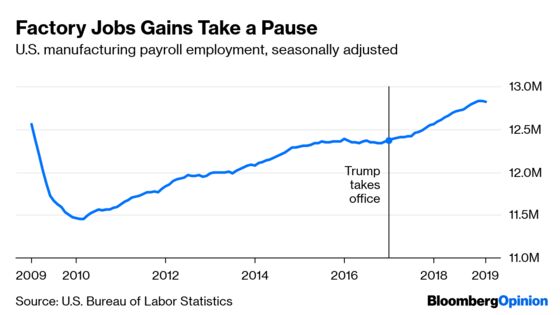

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Amid a generally pretty good jobs report Friday, one negative that stood out was that the manufacturing sector — which had been adding employment at a faster pace than the rest of the economy for the past two years — actually shed 6,000 jobs in March.

The culprit was mainly the automobile industry, as employment in motor vehicles and parts manufacturing fell by 6,300. But there weren’t really any super-hot manufacturing sectors. Also, while the numbers above are all seasonally adjusted, and the unadjusted data show a gain of 6,000 manufacturing jobs in March, it also shows a loss of 47,000 jobs since December, compared with a gain of 10,000 over that same period a year ago.

Given that manufacturing employment was the indicator I chose back in January 2017 as one of Bloomberg Opinion’s 17 metrics to watch to judge the progress or lack thereof of Donald Trump’s presidency — and that when last we checked in, a day before the January jobs numbers came out, it was looking “pretty great” — this is worthy of note. Is it worthy of a whole lot more attention than that at this point? Perhaps not. The IHS Markit manufacturing purchasing managers index is indicating a slowdown but not yet a downturn in manufacturing activity, while its Institute for Supply Management counterpart showed a big uptick in March after several months of declines. It’ll be a few more months before we know whether this is a blip or something bigger.

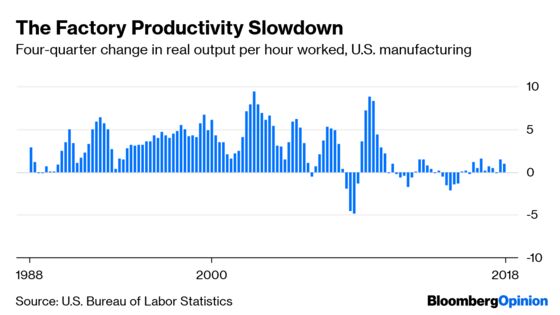

The manufacturing jobs pause does seem to offer more support, though, for my contention that the “Trump economy” — last year’s brief, fiscal-stimulus-assisted growth spurt notwithstanding — is mainly a continuation of the “Obama economy” that preceded it, a period of slow but long-lasting growth with some interesting characteristics. One of the most interesting is that while manufacturing employment has been experiencing its strongest run in decades, manufacturing productivity has been experiencing its weakest run in decades.

Harvard University economist Robert Z. Lawrence described this phenomenon in 2017, writing that it suggested “a tradeoff between the ability of the manufacturing sector to contribute to productivity growth and its ability to provide employment opportunities.” In the booming 1990s, big gains in manufacturing productivity were accompanied by more or less flat manufacturing employment; in the less-booming early 2000s and in the immediate aftermath of the last recession, spectacular gains in manufacturing productivity were accompanied by plummeting manufacturing employment. And since then, it’s been a slow-output-growth, high-employment-growth manufacturing recovery.

Creating more manufacturing jobs is good. Despite the disappearance in the past few years of what had long been a big hourly wage premium for workers in durable-goods manufacturing over other private-sector workers, manufacturing jobs have remained better-than-average jobs, especially for those without college degrees, with longer, more reliable hours and more generous benefits than most service work.

Without productivity growth, though, the prospects for faster economic growth and bigger wage gains dim. There is, as Lawrence argued, a trade-off. Still, this at least offers the possibility of a silver lining to the recent factory jobs slowdown — maybe it’s a sign that manufacturing productivity growth is about to pick up a little.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brooke Sample at bsample1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.