(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Boeing Co. is in a heap of trouble right now — there’s no getting around it. The two deadly crashes of its new plane, the 737 Max, killing 346 people, have cost it an enormous amount of reputational capital, and will undoubtedly cost it a lot of money — in lawsuit settlements, in multi-million-dollar payments to airlines that have had to ground the plane, and quite possibly, in lost sales if customers conclude that Airbus SE makes safer airplanes.

Boeing appears to have built the plane too hastily, in a panicked response to the early success of Airbus’s new plane, the A320neo. The Federal Aviation Administration appears to have ceded too much authority to the company in certifying the plane’s safety.

And although the company appears to be closing in on a software fix for the malfunction that most likely caused the crashes, it’s hard to know when the plane will be allowed to fly again. Even if the FAA finds the new software satisfactory, Canada, China and the European Union have all said that they will need to certify the 737 Max themselves before allowing it in their skies again. Oh, and last week, Indonesia’s state-run airline announced that it wanted to cancel a $4.8 billion order for the plane.

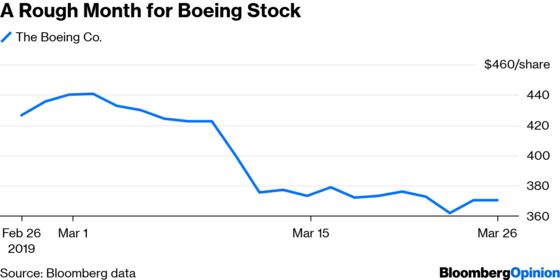

Not surprisingly, the stock has taken a hit; in the two and half weeks since the Ethiopian Airline crash on March 10, Boeing shares have fallen 13 percent. But if I were a hedge fund manager (in my dreams!), I would be buying the stock right now with both fists. Why? Because Boeing’s history strongly suggests that it will not only recover from this fiasco, but will do so quickly. And it will emerge stronger than ever.

Twenty years ago this month, a business journalist writing about the company began his appraisal with this sentence: “Boeing matters.”

At the time Boeing was in the same kind of trouble as the auto companies were when Japanese imports began making inroads in the U.S. market. Having once faced minimal competition, Boeing struggled as Airbus took away market share. Its production problems became so serious that for a stretch in 1997, it had to shut down two assembly lines and take a $1.6 billion charge against earnings. Its paternalistic culture was having a difficult time adapting to serious competition. In 1998, its stock price lost a third of its value.

But as the writer, Kenneth Labich, pointed out, Boeing was the largest exporter (in dollar volume) in the U.S. It was the biggest supplier to both the Pentagon and NASA. It not only had 230,000 people on its payroll, but its various suppliers employed another 700,000 workers. “All of which means,” wrote Labich, “that there are plenty of repercussions when the company stumbles” — not only for Boeing’s workers and shareholders, but also for the country.

Shareholders and others were calling for Boeing’s chief executive, Phil Condit, to be fired. Instead, Condit replaced the head of the commercial airplane division with Alan Mulally, who would turn out to be a manufacturing genius. Mulally transformed Boeing’s production processes, which substantially increased the division’s margins, while churning out more planes with greater efficiency. (Previously, Boeing’s commercial airplane margins had been less than one-half of one percent.)

It worked. Although Boeing suffered through several scandals in the early 2000s, causing the resignation of both Condit and his successor, Harry Stonecipher, it was able to successfully manage years of turmoil in the airline industry that followed skyrocketing fuel prices and the 9/11 terrorist attack. By the time Mulally left the commercial airplane division to take over as CEO of Ford Motor Co., in 2006, the company was generating orders for over 1,000 planes annually, while its revenue, cash flow and stock price were all reaching new highs.

Fast forward to 2008, when Boeing’s new 787 plane — the so-called Dreamliner — was supposed to be ready to fly. The midsize plane, which had been first contemplated in the early 2000s, had generated an impressive $160 billion worth of orders while it was still on the drawing boards. But it wasn’t ready in 2008 … or 2009 … or 2010. Because it used new composite materials — and new suppliers from around the world — it suffered all kinds of delays.

Even after it was finally in service in late 2011, it hit another serious glitch in 2013, when, on two occasions in Japan, its lithium ion batteries burst into flames after the flights had landed. Guess what? In the ensuing bad publicity, the plane was grounded by the FAA in January 2013 — just like the 737 Max today. The government didn’t allow it back in the air again until April. Regulators concluded that Boeing’s engineers hadn’t understood the batteries well enough, and hadn’t done enough testing.

Today, there are 800 Dreamliners in use, and another 600 on order. The stock was at $75 a share when the plane was grounded. Within a year, it had nearly doubled.

There is no doubt that the crisis Boeing is facing today is every bit as serious as its previous crises — more so, really, because passengers have died this time. Boeing is now being punished for allowing that to happen, as it should be. But the modern airplane is a phenomenally complicated piece of machinery. Inevitably, a new model is going to have unforeseen problems that need to be worked out. Will those problems be fixed? Without question. At which point the 737 Max and Airbus’s A320neo will go head to head in the marketplace. Both of them, I predict, will succeed.

There is one other point worth making. Good companies — companies of real substance — learn from their mistakes. In 1989, the Exxon Valdez struck a reef off the coast of Alaska, spilling almost 11 million gallons of crude oil and creating an environmental disaster. In the subsequent 30 years, Exxon Mobil has not suffered another serious spill. That’s not the result of luck.

Boeing will learn from this crisis, just as it has from past crises. It has to. Because Boeing matters.

The article made an especially big deal out of the fact that Boeing was the worst performing stock in the Dow Jones Industrial Average. Remember when people used to care about the Dow?

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Philip Gray at philipgray@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Joe Nocera is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He has written business columns for Esquire, GQ and the New York Times, and is the former editorial director of Fortune. He is co-author of “Indentured: The Inside Story of the Rebellion Against the NCAA.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.