Trump’s Student Visa Clampdown Hurts the Rust Belt

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- President Donald Trump has been making life more difficult for foreign students trying to study in the U.S. His administration has implemented much stricter review of student visas, has threatened to make it harder for international students to work, and even changed a website to hamper international students’ efforts to get jobs.

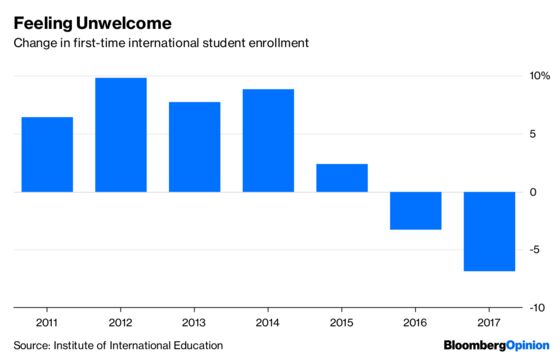

This constant stream of threats and harassment, in addition to the general climate of xenophobia created by Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric, is having an effect — in the year ended in September 2017, the State Department issued 40 percent fewer student visas than in 2015, and foreign student enrollment, which had already stopped rising during the 2016 election year, is now falling at an accelerating rate:

This policy would never be a good idea, but it comes at a particularly inopportune time. Many declining cities and regions are just starting to dig themselves out from the twin disasters of Rust Belt deindustrialization and the Great Recession. Especially in the Midwest, but scattered across the country, are towns that are looking for a new economic strategy to help them rebuild.

As Brookings researcher John Austin and writers James and Deborah Fallows have noted in their analyses of successful urban revivals, the most promising model for local revival revolves around universities. With the decline of small-town manufacturing, universities provide the tent-pole industry that generate what economists call local multipliers — revenue that comes in from outside and gets spent locally, spreading prosperity throughout a city.

There are many examples of how a university can revitalize a declining region, but my favorite one is my own hometown: College Station, Texas.

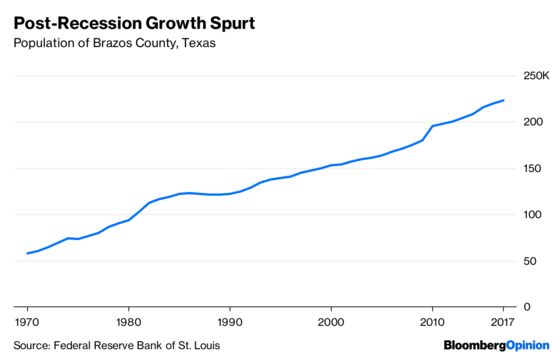

Situated right in the middle of the Texas Triangle (Houston, Dallas-Fort Worth, and Austin), two hours from any big city, College Station isn’t a suburb, but it’s always been a little too big to call it a small town. But it’s getting bigger. Since 1990, the town’s population has more than doubled, from about 53,000 to 112,000 as of 2016. The region is now becoming an urban agglomeration in its own right — Brazos county, which includes the adjacent city of Bryan, is now home to over 220,000 people:

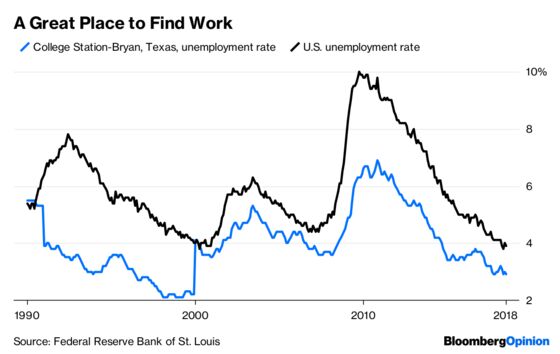

Even in the Great Recession, people were moving to College Station. And the city’s economy has found useful things for them to do — real wages have risen steadily, even as unemployment has stayed below the national average:

Visiting the town now, I can’t help but marvel at the apartment buildings and shopping centers that are sprouting up everywhere. Even as the American economy has had its ups and downs, College Station’s growth has barely paused for breath.

How did my sleepy Texas hometown accomplish this feat? It owes a debt to the local university, Texas A&M.

Once a school for farmers and mechanical engineers (hence its name), Texas A&M is now one of the country’s better educational institutions — U.S. News and World Report ranks it 24th in the nation among public universities. It has also grown to enormous size, ranking only behind the University of Central Florida by undergraduate population.

Texas A&M has fueled College Station’s growth in several ways. The vast student population spends locally on tuition, room and board, food, entertainment and everything else. The state government pumps money into the school from tax revenues, and the federal government via research grants. Companies also invest in the school — Texas A&M has pushed aggressively for commercialization of academic research.

Meanwhile, the university generates an educated workforce, some of which moves away after graduation, but some of which stays and works at places like Baylor Scott & White hospital. Top quality medical services, abundant retail, and the pleasant atmosphere created by the large student body have drawn residents into town from the surrounding countryside. For a long time, the pull of Texas’ big cities left College Station starved for corporate investment, but the educated workforce and university research partnerships may finally be tempting enough — Cognizant Technology Solutions Corp., a Fortune 500 company, moved its U.S. operations to College Station in 2013.

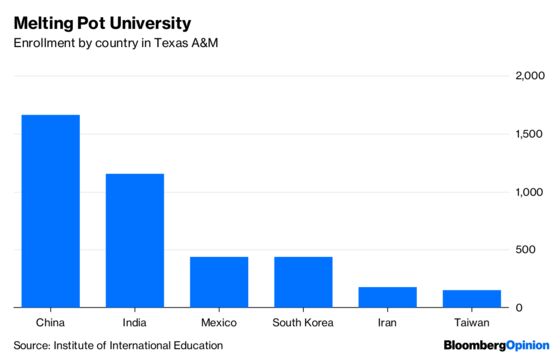

The university doesn’t just draw students from Texas and the rest of the U.S., but from around the world. As of spring 2016, Texas A&M had 5,471 international students enrolled, with China and India providing the most:

International students pay top dollar — $465 per undergraduate credit-hour in 2017-18, compared to only $50 for an in-state student. If each student takes 24 credit hours per year, that translates to about $50 million more in revenue for Texas A&M. Furthermore, that money represents pure gain for the state of Texas — a dollar of in-state tuition would otherwise have been spent elsewhere in Texas, while a dollar of international tuition would have been spent in China, India or elsewhere.

But the international students’ contribution to Texas A&M goes beyond money. Because the university can select from the vast talent pools of countries like China and India, they make its student body more elite. This helps contribute to building a skilled local workforce for companies looking to move to the city or partner with university labs. This is, of course, in addition to the contributions of international faculty, researchers and other workers, who will also find it harder to come into the U.S. thanks to a variety of Trump administration policies.

Trump’s immigration restrictions will hurt Texas A&M a bit, but their heaviest blow will fall on the still-struggling Rust Belt cities that could have used College Station and similar towns as a model for their own revival. Supporting a small city with a good university won’t be impossible — indeed, it will still probably be the optimal development strategy — but it will be harder than before. For the good of small declining cities across the country, Trump should reverse course and let in more talented people from overseas.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.