Yes, the Tax Cuts Have Cost the U.S. Treasury Money

The tax cuts have not cost the U.S. Treasury money, because the tax cuts boosted growth: Brian Wesbury

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Wow, do we really have to go through this again? Here’s Brian Wesbury, chief economist at First Trust Advisors LP in Wheaton, Illinois, and a long-time fan of tax cuts:

January - June 2018 total federal tax receipts are up 0.2% from January -June 2017 tax receipts. The tax cuts have not cost the US Treasury money, because the tax cuts boosted growth. Yes, the deficit is up, but thatâs because spending is up.

â Brian Wesbury (@wesbury) September 13, 2018

Just in case the bottom of that tweet was cut off in your browser, let me repeat Wesbury’s words: “The tax cuts have not cost the U.S. Treasury money, because the tax cuts boosted growth. Yes, the deficit is up, but that’s because spending is up.”

He’s right that spending is up! It was 3.5 percent higher year over year in the January-June period he references, and it’s up 7.4 percent from January-August 2017 to January-August of this year, according to the latest Monthly Treasury Statement. But that raises an interesting question: Since we now have data available through August, why is Wesbury citing January-June numbers? Well, maybe because, measured January to August, federal tax revenue is actually down 0.4 percent so far this year.

That’s strike one for the assertion that “the tax cuts have not cost the U.S. Treasury money.” Actually, it’s strikes one, two and three, because even by Wesbury’s standard, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 that President Donald Trump signed into law in December has so far cost the Treasury money. But it’s important also to point out — again and again, because people in Congress and elsewhere keep embracing the fallacy that tax cuts reliably increase revenue — that his standard is ridiculous.

It’s ridiculous first of all because it ignores inflation, which, as measured by the Consumer Price Index, averaged 2.1 percent over the first half of this year, turning that 0.2 percent January-June gain into a 1.8 decline in real tax revenue. Substitute the deflator used in calculating real gross domestic product, and it’s a 1.9 percent decline.

Even if tax revenue had increased in real terms, though, this still wouldn’t demonstrate that the tax cuts hadn’t cost the Treasury money. That’s because real tax revenue usually goes up when the economy is growing. So when the Congressional Budget Office or Joint Committee on Taxation makes an estimate of the revenue losses from a tax cut, they aren’t saying that tax revenue will go down by that amount in absolute terms; they’re saying that it will be that much lower than they think it would have been in the absence of the tax cut.

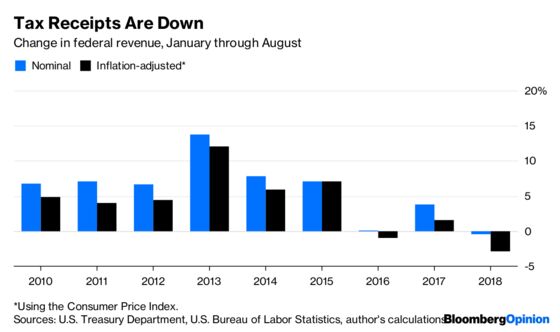

That can be a little hard to get one’s head around, I realize, but a graphic representation may help. Here’s the change in January-August tax receipts for every year of the current recovery, both in nominal terms and adjusted for inflation:

This year so far stands out as especially bad for tax revenue, then. So, to a lesser extent, does 2016. The explanation then was a price bust that hammered the oil and gas industry and a strong dollar that hammered exporters, with real GDP growth slowing to a 1.9 percent annualized pace over the first three quarters of the year. In 2018, on the other hand, real GDP has grown at a 3.2 percent annualized pace over the first two quarters, and even if you argue (as I have) that at least part of this year’s acceleration in economic growth is due to the stimulative effect of the tax cuts, those tax cuts have still clearly cost the Treasury a lot of money.

Then again, they wouldn’t really be tax cuts if they didn’t cost the Treasury money, at least initially. There is a theory, expounded with the most detail and enthusiasm by the Tax Foundation, that the corporate tax changes in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act will eventually generate so much additional investment and economic activity in the U.S. that they will more than pay for themselves. But this would take a while; so far this fiscal year (which started in October 2017), corporate income tax revenue is down 30 percent in nominal terms, according to the Treasury Department.

Individual income tax revenue is up 7 percent, but most of the revenue impact of the individual tax cuts in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act isn’t expected to be felt until the next fiscal year as people file their first tax returns under the new law and the limited partnerships, limited liability companies and S corporations that are taxed as individuals puzzle through the 184 pages of new pass-through taxation rules that the Internal Revenue Service released just last month. There’s also less expectation that the individual tax cuts could conceivably pay for themselves. According to the Tax Foundation, congressional Republicans’ new proposal to make all the currently temporary individual provisions in the tax law permanent would boost GDP by 2.2 percent over the long run but cost $112 billion a year in tax revenue even with that added growth factored in. According to the Penn Wharton Budget Model, it would reduce GDP by 0.6 percent to 0.9 percent by 2040 and cut tax revenue by $188 billion a year.

Those are projections, based on complex macroeconomic models that may or may not be right. What we can say with certainty right now, though, is that the enactment of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act has been followed by a decrease in federal tax receipts.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brooke Sample at bsample1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.