(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Russia, according to Deputy Finance Minister Vladimir Kolychev, is ready to buy back its own domestic debt on the open markets if the U.S. sanctions it or if volatility becomes substantially higher than normal. The idea makes sense if one views foreign bondholders as a source of instability – and that’s how a country like President Vladimir Putin’s Russia should see them.

In February, UniCredit said in a research note that in some emerging markets, foreign ownership of a country’s domestic debt is highly correlated with its currency’s nominal exchange rate. A 1 percent increase in foreign ownership leads to a 0.47 percent appreciation of the national currency in Hungary, 0.8 percent in Indonesia and Mexico and 1.4 percent in Turkey.

Now one can see this effect in action: Even if the absolute numbers don’t quite fit the UniCredit model, the direction of the trend is clear. So far this year, foreign investment in Turkey’s domestic debt is down about 55 percent, according to data compiled by Bloomberg, and the Turkish lira is down 43 percent relative to the U.S. dollar. In Russia, foreign ownership dropped about 10 percent betwen the start of the year and the end of July; the ruble is down almost 16 percent in the year to date. But foreign investment in Mexico’s debt is up 0.2 percent, and the peso is up almost 2 percent.

One of the reasons of the currency contagion in emerging markets this year is that rate hikes have made U.S. assets more attractive, and investors who plowed the liquidity created by years of lax monetary policy in the rich world into emerging markets assets no longer have as much appetite for risk.

Foreign investment in a country’s bonds strengthens the currency and tightens yields, but foreigners are often the first to flee at any sign of adversity; their reactions to negative news are often more pronounced than those of domestic investors, perhaps because the latter have fewer investment options or more faith in their country than yield-hunting foreigners are willing to put in a foreign land. In May, just as foreigners stepped up Turkish bond sales in response to President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s announcement of an early elections and plans to take more personal control of the economy, Goldman Sachs told investors to be careful of emerging markets with a lot of foreign-owned debt.

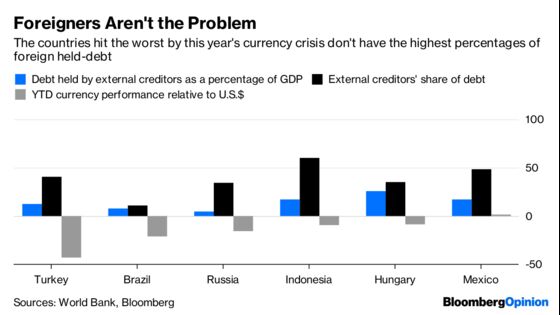

The nationalist governments of Eastern Europe, notably Hungary and Poland, have long viewed the large foreign holdings of their debt as a danger signal. To them, it’s a measure of sovereignty loss and external dependence. In a Bloomberg interview earlier this year, Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki spoke proudly of reducing the share of Poland’s debt in the hands of non-residents to 50 percent from 60 percent three years ago. But, judging by the latest currency crisis, the share of debt in foreign hands isn’t the problem, whether viewed relative to a country’s total debt or its economic output.

It’s not the emerging economies with the biggest share of non-resident debt holdings, and not even those with the biggest absolute amounts of foreign-held debt, that have taken the biggest hit in the current crisis. It’s the ones that have generated the worst news.

Turkey has suffered from Erdogan’s economic high-handedness and the obvious consolidation of his authoritarian regime. Brazil faces an election with a highly uncertain outcome and a set of top candidates none of which endears himself to investors. Russia has been hit by increasingly harsh U.S. sanctions and there’s no end to this in sight. Argentina and South Africa, the two other countries with currencies among the worst five this year, face serious questions about the adequacy of their economic policies.

It’s to bad-news countries that foreign-held debt presents a danger. If you run a nation that tends to produce negative headlines from investors’ point off view – that is, if you’re Putin, bent on resisting the U.S., or Erdogan, interested in ever-increasing control – any serious amount of foreign-held debt is a problem. Foreigners will flee your country first, putting pressure on the national currency. Domestic investors, meanwhile, might stick around simply because they have a longer-term outlook and more understanding of the situation on the ground than news stories can provide.

That makes measures like debt buybacks reasonable even outside an emergency context if they can be afforded. For Russia, foreign bondholders will be a net benefit only if the country resolves its conflict with the U.S. Since that prospect grows more distant every day, buying up the bonds foreigners sell is what the doctor has ordered for currency stability – and the kind of economic sovereignty eastern European nationalists crave.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Therese Raphael at traphael4@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European politics and business. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.