Maybe Worker Inequality Isn’t Inevitable After All

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- In the 2000s and coming out of the great recession, increased inequality between educated knowledge workers and less-educated and goods-producing workers seemed inevitable. For college-educated workers, there were three areas of job growth: office jobs, education and health care. Goods-producing jobs like those in the manufacturing and construction industries were slowly shrinking as a percentage of total employment, and younger workers were better off staying away from those industries. Less-educated workers got stuck with whatever was left, typically in industries like retail or leisure and hospitality.

But as we head into the waning months of the 2010s, there's reason to believe a more balanced picture is emerging, with prospects particularly promising for workers and industries thought to be left behind.

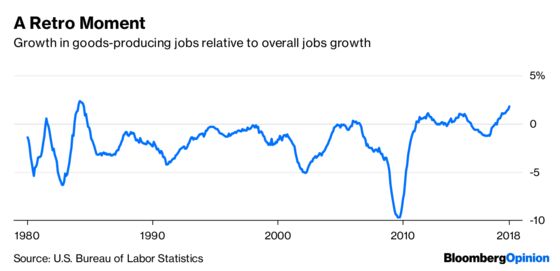

The biggest labor-market surprise these days, affirmed in Friday's jobs report, might be that goods-producing job growth is surging, and the rate has continued to accelerate. Its growth is currently outpacing overall job growth by the largest amount in over 30 years.

It's possible that 2018 represents a perfect confluence of events for this category of employment, and we'll look back on it as a fluke. Construction employment growth continues to chug along as the housing market recovers and the industry tries to catch up after years of under-building. Energy-sector employment continues to recover after the sector's bust a few years ago. Manufacturing job growth has been surprisingly strong, in support of the construction and energy sectors, and in response to demand factors like the freight industry being short of trucks.

Whether it's a fluke or a new normal, the U.S. economy has created over a million net new manufacturing jobs in the 2010s, which would be the first time we've created a million manufacturing jobs since the 1960s. There was growth every year except 2016. The industry might never power the national economy again the way it did a half century ago, but it may end up being a more stable source of employment than we recently thought.

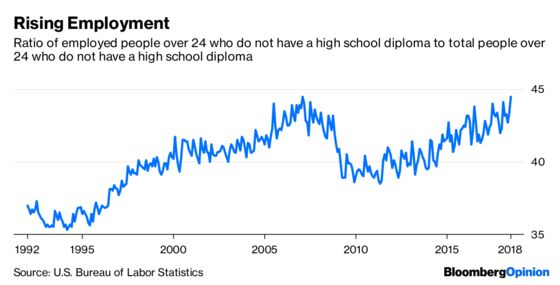

And then if we look at which demographic groups are faring better in the job market than at any other time on record, those with less than a high school degree top the list. The unemployment rate for people over age 25 with less than a high school degree is 5.1 percent, the lowest on record going back to 1994. Perhaps more impressive, as economists point to the employment-population ratio still being below its highs of prior cycle peaks to argue there's still more labor market slack, that is not the case for those with less than a high school degree. For that subset of workers, its employment-population ratio in July matched its record high set in 2007.

This dovetails with a piece written last week by Jason Furman, former chair of President Barack Obama's Council of Economic Advisers. In it, he shows that the reason wage growth is currently lower than it was in the late 1990s is that both inflation and productivity growth are lower now than they were back then. Adjusted for that, the labor market is just as strong. But in terms of the composition of wage growth, the late 1990s was a time of widening income inequality, with high earners pulling away from low earners. Today, by comparison, the lowest-paid earners have the fastest wage growth. As the labor market continues to tighten, and as minimum wage levels go up around the country, the lowest-paid and presumably least-educated workers should continue to see strong wage growth.

This isn't to say that income inequality isn't a problem or that we shouldn't be doing more to help workers, but it shows that for two groups of workers thought to be left behind -- goods-producing and the least educated -- things are actually moving in the right direction. They're currently benefiting from the economic environment more than workers at the high end of the income scale. And as we look ahead to the 2020s, we shouldn't be so sure that the labor market's inequality is inevitable.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Philip Gray at philipgray@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Conor Sen is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He is a portfolio manager for New River Investments in Atlanta and has been a contributor to the Atlantic and Business Insider.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.