(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Many books have been written about East Asian industrial policy — government efforts to pick winning industries and nurture economic development. There has been some attention to European initiatives as well.

In comparison, relatively little has been written about modern U.S. industrial policy. Advocates of a more purposeful government role in American economic development often hearken back to the age of Alexander Hamilton or Franklin Roosevelt, contrasting them with the modern era of laissez-faire policy and finance-driven capitalism.

But at the local level, it’s a different story. Even as the U.S. federal government has largely refused to pick winners (except perhaps for the financial sector), cities and towns have been vigorously working to promote specific business and industrial clusters. Those local efforts have received relatively little attention, but they could be key to the revival of many of the country’s struggling regions.

Veteran journalist James Fallows and writer Deborah Fallows (a married couple) document this process in their recent book, “Our Towns: A 100,000-Mile Journey into the Heart of America.” The book is billed as a Tocquevillian quest to rediscover the heart of American small-town civic cooperation and democracy — a pushback against claims by people like sociologist Robert Putnam that the country is falling into a state of isolation and anomie. But it’s also an insightful and penetrating exploration of how American cities can get back on their feet after devastating blows from the Great Recession, the China trade shock and the deindustrialization of the Rust Belt.

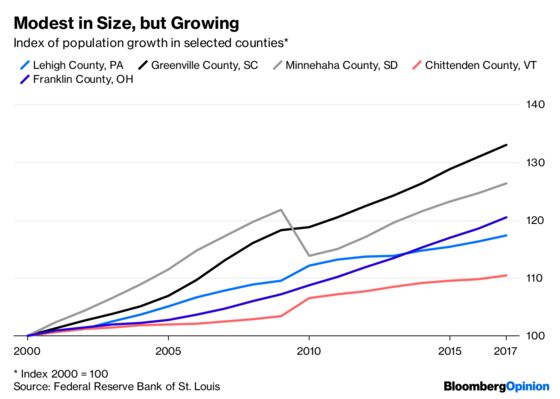

Traveling across the country in a light aircraft, the authors avoided the big coastal cities that tend to capture headlines and attention. Despite the title, they actually visited only a few small towns and rural areas — most of their targets are medium-sized cities like Allentown, Pennsylvania, or Greenville, South Carolina. These tend to be places with populations numbering in the tens of thousands — large enough to sustain a downtown, but not large enough to become major industrial clusters. They also tend to be places with growing populations:

The authors notice a number of common approaches among towns that are on the mend. Two of these are themes I’ve discussed a lot myself: universities and immigration.

Universities educate locals, creating a skilled workforce and making a town an attractive destination for companies looking to invest. But actually, as Fallows and Fallows note, this is a function best served by community colleges and specialized public schools. Research universities’ function is different — they draw highly skilled individuals to a town, some of whom then start businesses and do other high-value work. Of course, college students and government research dollars also buoy local demand.

Immigrants, meanwhile, support a declining region’s tax base. As native-born Americans have forsaken small cities and the interior for the glitz and glamour of coastal metropolises, an influx of foreigners has been the only thing keeping many towns’ coffers filled. The authors describe a number of places where immigrants — skilled workers from Asia and elsewhere, laborers from Mexico and Central America, and refugees from war-torn countries in the Middle East and Asia — have started businesses and local civic organizations, boosted tax revenues, provided a local labor force to lure business investment, and provided a shot of energy and cultural vitality to places that would otherwise have become ghost towns. When describing how immigrants have changed the heartland, Fallows and Fallows paint a hopeful picture of integration and tolerance — a direct rebuke to the dark visions of racial conflict currently being offered by some in the national media.

The pair identify some other successful approaches in addition to the mainstays of universities and immigration. One is the presence of local leaders who bring together government, business and nonprofits to carry out big projects. Reading some of these examples, I was reminded of Pike Powers, the consultant who helped create the public-private partnerships that made Austin, Texas, a world-class tech cluster. Another element they point to is a successful, thriving downtown.

In general, Fallows and Fallows find that the most successful cities are those where the government, the private sector and nonprofits all work in concert with one another. This idea of public-private partnership stands in contrast to free-marketers’ disdain for government intervention, as well as socialists’ contempt for the profit motive of corporations and entrepreneurs. To save a city, the authors write, you need both. Public-private partnerships can provide the specialized education needed to nurture a flagship industry like aerospace manufacturing or agricultural technology. They can provide needed infrastructure, revitalize downtown areas, lure companies away from big cities, and work to funnel immigrants into gainful employment. This is the essence of local industrial policy.

Although they don’t explicitly say it, Fallows and Fallows also provide a road map for how the American heartland needs to change. A landscape of small towns with populations in the hundreds or thousands needs to consolidate into a patchwork of small cities with populations in the tens of thousands. Small cities like the ones the authors visit offer much of the comfort, space and friendliness of the small-town atmosphere, while also taking advantage of agglomeration economies. And larger towns are much better equipped to carry out successful industrial policies of the type Fallows and Fallows describe.

The U.S. has been hit by many economic shocks and dislocations during the past half-century. But its local government, business and civic leaders have never stopped working to revitalize their towns, instead of giving up and moving to the coast. Their valiant efforts shouldn’t be left out of the national conversation.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.