(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Expectations were approaching ebullience heading into this spring’s U.S. home-selling season. The National Association of Realtors entered the year expecting home sales to grow by 3.7 percent in 2018 after last year’s lackluster 1.1 percent increase. But now, the NAR’s chief economist has tempered his call with existing homes changing hands at the slowest pace since September and new home sales having fallen to the lowest level since October 2017.

With home prices at or near record highs, it takes more than a small boost to income to call potential buyers to action. The average household has to save for almost six and a half years to cover a 20 percent down payment on a home at current prices, according to a recent study by Zillow HotPads. That’s based on the steep assumption that workers can sock away 20 percent of their monthly take-home pay. Saving money is especially tough for renters. Zillow calculated last year that just 42 percent of rentals were affordable, defined as requiring 30 percent or less of one’s median monthly income to cover rent payments.

Perhaps reflecting the affordability obstacles, the Conference Board’s consumer confidence data for July released Tuesday showed that plans to buy a home in the next six months tumbled to the lowest level since June 2016.

The cost to rent and buy has become particularly acute in major markets, especially if you prefer a home to an apartment. Renting a three-bedroom house is more expensive than buying a median-priced home in 54 percent of major markets, according to ATTOM Data Solutions. The average three-bedroom runs renters 38.8 percent of their annual income.

There are other factors that have hamstrung the housing market in 2018 besides record-high home prices. Mortgage rates for 30-year fixed loans are up by more than 0.8 percentage point on average. Separately, the new tax law limits all state and local income taxes and property taxes that can be deducted to $10,000.

Affordability is even more elusive among middle-tier income earners, who tend to be in the market for move-up homes after they’ve outgrown their starter home. And that’s in second-tier markets. In the nation’s costliest cities, median home prices often exceed the wherewithal of most regardless of how much they make. In San Francisco, average home prices exceed $1.6 million.

Let’s take the example of moving from what Zillow classifies as the middle third of homes nationwide, which is the median price we always hear quoted of $217,300, up to what Zillow categorizes as the top third of homes by price nationwide, the median price of which is $380,100. Those are what many realtors would call “move-up” homes.

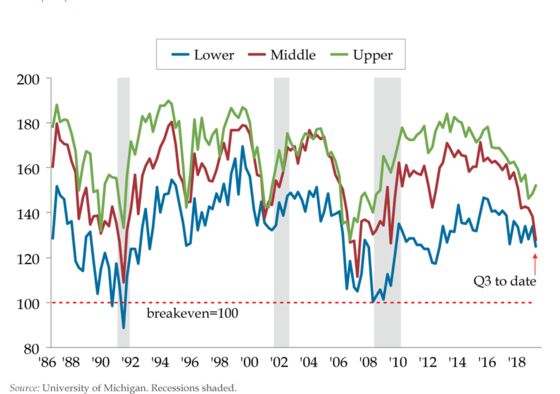

For the sake of simple illustration, let’s compare the rate two years ago to what it is today for a 30-year fixed mortgage. Back then, the rate was (assuming no points) 3.63 percent compared with 4.75 percent today. The monthly payment for a couple who has just had a second child and wants to upsize would double from about $792 to $1,585. Had mortgage rates stayed where they were two years back, that same payment to move up today would be $1,386. It’s no wonder that according to the University of Michigan, buying conditions among middle-tier income earners has fallen out of bed of late. If you have designs on living in a better school district that doesn’t require private school tuition for the tykes, be prepared to pay a hefty premium.

The Bottom of the Housing Market Falls out of the Middle

The protracted decline in top-tier home-buying conditions could be a mere starting point that trickles down through the lower tiers. The top third of income earners account for 60 percent of the dollar value of “owned dwellings,” as per the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Expenditure Survey. This group, albeit small, has more incentive than ever to stay put or move to a lower-tax state.

Consider a homeowner who bought a home a few years back who locked in a low rate on a $700,000 mortgage. That home has appreciated to $1 million, but interest payments remain about $24,500 a year, or $15,500 when adjusted to a top 37 percent tax rate and principal paid down. If this homeowner upgrades to a $1.2 million abode with a $975,000 mortgage, which takes into account transaction costs, mortgage interest would jump to $45,500. Adjusted for taxes, the marginal cost would be $32,500.

The alternative to the $17,000 budgetary upcharge is a facelift. For the same homeowner, a maximum of $50,000 would be deductible on a home equity line of credit given they would bump up against the new $750,000 limit. Even so, if the homeowner plunked $100,000 into an upgrade, the tax-adjusted, bottom-line interest increase would only be $4,000.

It would seem mobility will no longer be a hinderance unique to the millennials. The economy has always keyed off residential real estate. Investors would be well-advised to keep housing at the top of their watch lists.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Robert Burgess at bburgess@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Danielle DiMartino Booth, a former adviser to the president of the Dallas Fed, is the author of "Fed Up: An Insider's Take on Why the Federal Reserve Is Bad for America," and founder of Quill Intelligence.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.