(Bloomberg Opinion) -- “Unhappy is the land that needs a hero,” wrote Bertolt Brecht in “Life of Galileo.” But there are times when countries and companies do need someone to step up; when the situation is so dire that only a radical makeover will do.

Sergio Marchionne, who died last week at the age of 66, was that person at Fiat and Chrysler — a savior at least to their workers and shareholders. He took two car companies on the edge of failure and, after a deep restructuring, turned the merged entity (Fiat Chrysler Automobiles NV) into the world’s seventh-biggest automotive group.

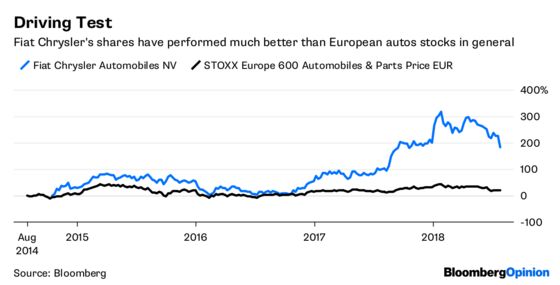

While there are understandable questions about why his serious illness wasn’t disclosed, his record of value creation was impressive: Fiat’s market capitalization increased more than tenfold under his 14-year stewardship.

The poker-loving executive will be remembered for his bold deals. In 2005, he convinced General Motors Co. to pay Fiat $2 billion so that the U.S. car giant wouldn’t be forced to take over the Italian company’s near-bankrupt autos business. But Marchionne could innovate, too. He introduced new production processes across Fiat factories in Italy. A car plant in Pomigliano d’Arco, once rife with inefficiency and absenteeism, is now considered among the world’s best-run.

Italy could certainly use a dose of that managerial expertise, both in its political class and its corporate elite. Much like Fiat in the mid-2000s, the country is struggling with stagnant productivity.

The new populist coalition is unfortunately taking steps that will make Italy less attractive to investment. But many of the country’s corporate leaders are equally culpable. In the absence of an overhaul in their thinking, it’s hard to see where efficiency gains will come from.

Several academic studies put poor leadership at the heart of Italy’s productivity crisis. Nicholas Bloom, Raffaella Sadun and John Van Reenen of Stanford, Harvard Business School and MIT, have shown that management accounts for half of the gap in total factor productivity — a measure of the economy’s efficiency — between Italy and the U.S. In fairness, that’s in line with other western countries such as France and Sweden, but it’s higher than the global average of 30 percent.

One reason for Italy’s bad showing is its failure to keep pace with the technology revolution that started in the mid-1990s. U.S. companies are often better than their European rivals at reorganizing their workplaces by using metrics that reward good performance. Luigi Zingales at Chicago Booth and Bruno Pellegrino, at the UCLA Anderson School of Management, say this weakness in IT and meritocratic business models explains up to half of the shortfall in Italy’s total factor productivity growth.

And it’s not just the U.S. that’s in front here. Two other academics found that inefficient management caused 28 percent of the productivity gap between Italy and Germany between 1995 and 2008. Again, Italy’s managers were slower at embracing the internet and made poor choices on IT. What’s worse, the resulting wage gap with more technologically advanced countries forced highly skilled Italian workers to move abroad.

It’s worth pointing out that Marchionne wasn’t always a hero to everybody in the Italian business community. He had to take Fiat out of Confindustria — the country’s entrepreneurs association — so that he could make the changes to employment contracts that let him boost productivity at Fiat’s Italian plants. Such moves are always unpopular, but a shot of this boldness would do wonders for Italy Inc.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Ferdinando Giugliano writes columns and editorials on European economics for Bloomberg Opinion. He is also an economics columnist for La Repubblica and was a member of the editorial board of the Financial Times.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.