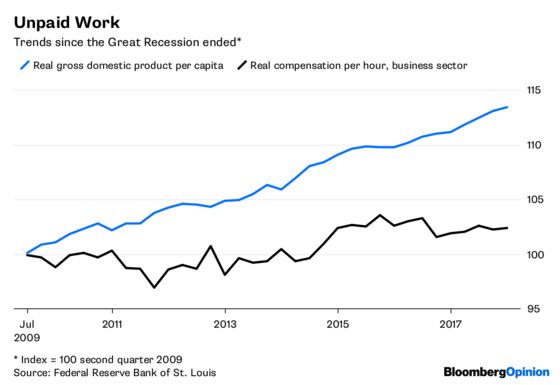

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Capitalism isn’t working right. The U.S. economy is growing, but workers are seeing less and less of the benefits. Since the Great Recession, real gross domestic product per capita has increased substantially, but real compensation per hour — which includes benefits like health care — hasn’t grown at all:

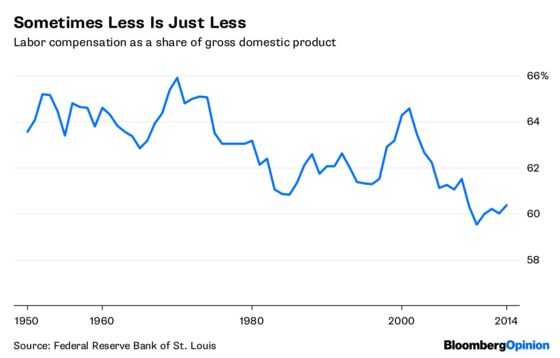

This continues the disturbing trend of labor receiving less of the national pie:

Stagnating wages are eating away at the very heart of the free-market economy. The economy keeps growing, but Americans are finding it harder and harder to be more prosperous than their parents.

If capitalism only works for the relatively small slice of society that owns large amounts of capital, few people are going to see the value in the system. Eventually they’re going to turn to alternatives, like the socialism now gaining popularity within the Democratic party and the younger generations.

Anyone who cares about preserving the free-market system should therefore be thinking very hard about how to raise wages. One idea is to change regulations and laws to make labor unions more powerful. Another is to strengthen antitrust enforcement to break up so-called superstar companies and prevent them from growing huge in the first place.

Both of these approaches would require a big push at the federal level. That is unlikely to happen without a change of administration, and probably without major shifts in the country’s political economy. But there are some simpler, humbler changes that state governments can begin taking right away, without waiting for labor-friendly politicians to take control of the White House and Congress.

One of these is to ban noncompete agreements. These bar employees from going to work for a company’s competitors, short-circuiting the process of competition by which companies bid up wages. Simply banning this type of anticompetitive contract would help bring back bidding wars that increase workers’ power and pay. Some states, like California, have already done this.

Another step is to vigorously police companies that try to collude to suppress wages. Most businesses, given the chance, would prefer to make agreements with their competitors to pay their workers less, thus preventing the need for a bidding war.

This is generally illegal, under the Sherman Antitrust Act. Fortunately, the Department of Justice has begun to prosecute wage-fixing and antipoaching agreements more aggressively. In 2015, technology companies Apple, Google, Intel and Adobe were fined for colluding to hold down the wages of tech workers, after a similar ruling against Lucasfilm and Pixar in 2013. Fortunately, this trend seems to be continuing even under the Trump administration, with the DOJ successfully bringing a lawsuit against Westinghouse Air Brakes Technologies and its competitor Knorr-Bremse AG. More efforts might be coming in the health-care industry.

But there is one area where antipoaching agreements might still be legal — franchise chains. Many franchises stipulate in their contracts that franchise owners aren’t allowed to hire each other’s workers. If you were a tax preparer working at an H&R Block franchise as recently as 2015, for instance, you couldn’t get a raise by hopping to a different H&R Block, or even getting an outside offer from a competing chain. As franchise chains grow in size and importance, this could mean fewer and fewer opportunities for workers to change jobs and get raises.

In a new paper, economists Alan Krueger and Orley Ashenfelter examine the data, and find that 58 percent of franchise chains had antipoaching clauses in 2016. The collusion covers a wide range of industries, from gyms to auto-repair services to tax preparation and restaurants (though it’s uncommon in the hotel and real-estate industries). The agreements are more common in low-wage industries, suggesting that it’s the most vulnerable workers who suffer the greatest harm from this collusion.

Fortunately, states are beginning to respond. A group of several states has launched a joint investigation into antipoaching in the fast-food industry. Some chains, such as McDonald’s, Arby’s and Cinnabon, have already agreed to give up the practice. H&R Block has done so as well.

That’s a welcome move. It shows that at least some state governments are not waiting around for the federal government to step in, and are not being overly cautious about precedent. The attack on collusion in fast-food franchises should be expanded to other industries. And state laws should be changed to explicitly ban antipoaching agreements at franchises.

A retreat on antipoaching could also kick off a more general assault on monopsony power at the state level. States can step up their own independent investigations of illegal wage-fixing collusion. Minimum-wage laws could be adjusted so that areas with few employers have more stringent pay requirements for the dominant local players. There are a number of ways that states can help push back against the trends of wage stagnation and decreased competition — and perhaps help to save capitalism from itself in the process.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.