The Working Poor Need Help. Keep the Expansion Alive.

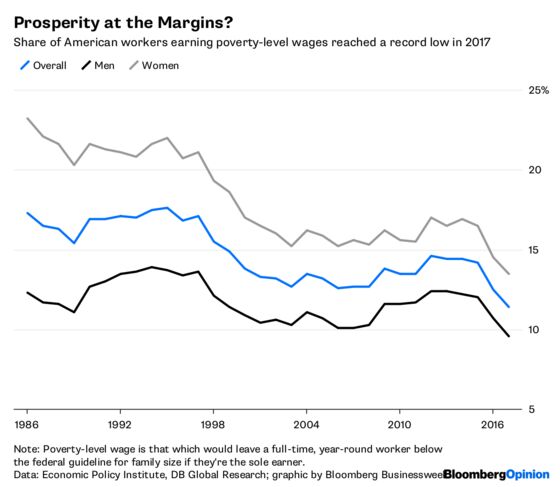

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Bloomberg recently reported on some interesting new data from the Economic Policy Institute. The percent of Americans earning poverty wages -- pay that would leave someone's family impoverished even if they worked full-time -- is at its lowest level since data began to be collected in 1986:

But the drop hasn’t been steady and uniform. Although the employment rate has been rising since 2012 or 2013, only recently have we again begun to see news stories about low-wage workers getting a raise.

And looking at the graph, we see that all of the gains for low-wage workers have essentially occurred in two periods -- the late 1990s, and the past three years.

Of course, three decades is a relatively short sample -- the pattern could be a coincidence. But it’s interesting that the sustained drops in poverty-level wages both occurred at the end of long economic expansions. The expansion that ran from March 1991 through March 2001 was the longest in postwar U.S. history, at 120 months, and the current expansion, which began in June 2009, is already the second longest, having run for 108 months. In both cases, the gains for low-wage workers started coming six years in.

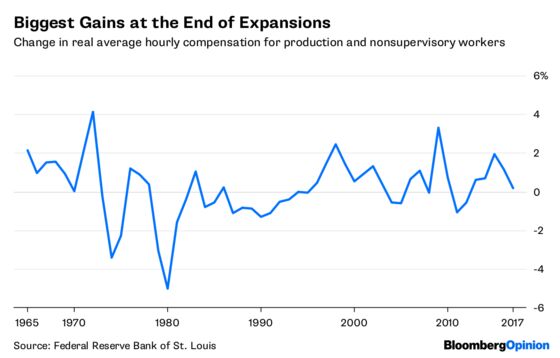

Some other measures of wages go back further. Looking at the change in real average hourly earnings for production and nonsupervisory workers, we see a lot of volatility, but there’s another sustained increase in the late 1960s -- right at the end of the third-longest postwar expansion:

It makes sense that low-wage workers would be the last to benefit from an economic boom. As the economy grows after a recession, companies are quick to snap up the most productive workers, but don’t hire the less productive people unless there’s no one else to hire. So the workers most likely to be near the poverty line probably get hired last. There’s some evidence that these productivity differences represent only a modest effect, but there could also be other reasons why low-wage employees are the last to join the workforce. Some people might earn so little in the market that welfare benefits, combined with a quasi-job in the gray-market economy, is a more attractive choice. Poor people may simply be the last to hear about job opportunities, or may suffer more discrimination, meaning it would require more economic pressure for businesses to go out and hire those workers.

But whatever the reason, this means that low-wage workers are probably the last to re-enter the ranks of the employed. And after the economy reaches full employment, increased demand probably causes companies to engage in a bidding war, trying to poach each other’s employees, driving up wages. That means that low-wage workers should see their pay bid up only after an expansion has run its course.

It’s also notable that the wage gains in the late 1990s weren’t lost in subsequent slowdowns -- even in the Great Recession, real wages fell only slightly, and the percent of workers earning poverty wages rose only a little bit. That could be due to downward wage rigidity -- the tendency of companies not to cut wages during a recession. When inflation is low, as it has been for the past three decades, downward wage rigidity means that real wages tend not to fall. Alternatively, some of the structural factors putting downward pressure on real wages in earlier decades -- the shift of manufacturing to services, for example -- might have run their course by the turn of the century.

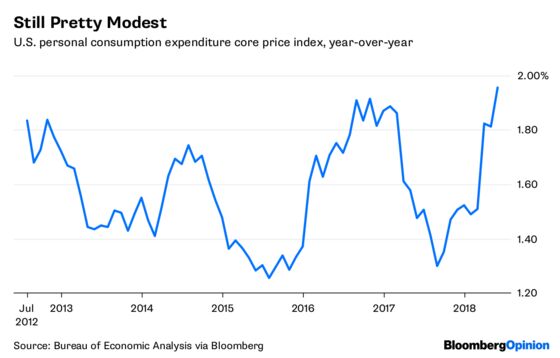

Whatever the reason, it’s an argument for keeping the current expansion going as long as possible. With inflation inching up over the past four months, the Federal Reserve must certainly be tempted to accelerate the pace of interest rate hikes:

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has said that global growth justifies raising interest rates more. According to standard economic theory, that will reduce aggregate demand, possibly slowing or even ending the expansion. Many believe that it’s the Fed’s job to, as the saying goes, take away the punch bowl before the economic party gets out of hand.

But this could have a downside. The late stages of expansions may be the only time when the business cycle really works to the advantage of the country’s poorest and most vulnerable workers. Keeping the party going might go against central bankers’ instincts, but failing to do so could exacerbate inequality and deny low-paid workers the chance to escape poverty. The Fed shouldn’t worry too much about inflation, which at this point remains tame, and should try to prolong this expansion as long as possible.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.