Why the U.S. Worries About U.K. Military Commitment

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- A leaked letter from U.S. Defense Secretary James Mattis to his U.K. counterpart Gavin Williamson suggests that the U.S. is unhappy with U.K. military spending. Mattis even appeared to hint that France might take the U.K.’s place as the preferred military partner unless the Brits get their act together.

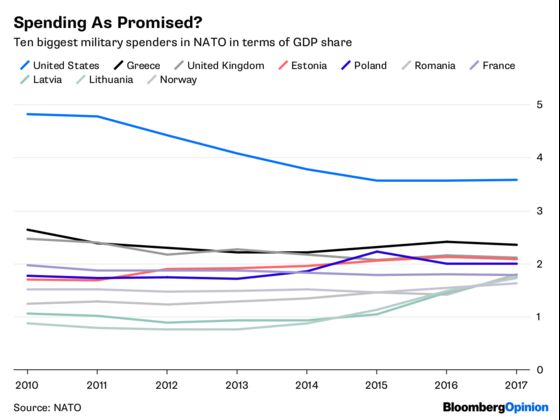

But wait a minute: Of NATO members, isn’t the U.K. an A student when it comes to defense spending? According to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, only the U.S. and barely solvent Greece spent a greater share of economic output on defense last year. Moreover, unlike most other NATO members, the U.K. has consistently spent more than 2 percent of its gross domestic product on the military, never failing to fulfill the obligation that U.S. President Donald Trump has held up as a measure of loyalty to the alliance.

In absolute terms, too, it’s the second-biggest defense spender in NATO after the U.S., with $55 billion in last year’s outlay. And it’s not spending most of its budget on personnel, the way Turkey and many of the smaller alliance members do; at 22 percent of the total, its equipment spending share is closer to France’s 24 percent and the U.S.’s 28 percent than to pacifist Germany’s 14 percent.

So if the U.S. has a problem with the U.K.’s commitment, could it be satisfied with any of its allies at all? And could Mattis be serious about France, which has chronically failed to spend 2 percent on the military? Didn’t French President Emmanuel Macron, soon after taking office last year, cause the head of the French armed forces, General Pierre de Villiers, to quit in disgust over proposed budget cuts?

Mattis, however, does have some valid reasons to be “concerned,” as his letter states, about the U.K.’s continued ability to provide a “critical military foundation” for diplomatic success.

The U.K.’s ability to maintain defense spending of more than 2 percent GDP is in question. Earlier this year, the International Institute for Strategic Studies published its annual Military Balance, claiming the U.K.’s actual military outlay last year amounted to 1.98 percent of its GDP because the U.K. economy increased faster than the defense spending. In recent years, the U.K. has only stuck to the 2 percent rule by changing what it includes in the calculation — military pensions, the defense ministry’s revenues, the costs of intelligence services. NATO has accepted the accounting changes because they’re generally in line with U.S. practice and because it’s understandably interested in showing compliance among its members. Adjusted for inflation, the U.K. spends less on its military today than in 2010.

The U.K. has a 180 billion pound military equipment procurement plan until 2027, but earlier this year, the National Audit Office declared it impossible to fund in full. Because of chronic underfunding, equipment cannibalization is growing. Last year, government auditors found it had increased 49 percent in the Royal Navy in the previous five years.

Although U.K. spending on actual military operations has closely tracked the U.S. pattern, rising and falling in sync with the senior partner’s outlay, the U.K.’s investment in the wars it’s been fighting alongside the U.S. is peanuts compared with what the U.S. chips in. In the 2016-2017 budget year, the U.K. spent 666 million pounds ($873 million); U.S. direct spending on “overseas contingency operations” has averaged $61 billion in the last three financial years.

Of course, no other NATO country, apart from the U.S., has even done as much as the U.K. It’s understandable, however, that recently, Mattis has been happier with France. Macron this year announced a plan to boost France’s military budget by 1.7 billion euros ($2 billion) a year until the end of his presidential term in 2022, and he’s bringing back compulsory national service for 16-year-olds. De Villiers likely resigned too quickly: The French president believes in repairing and replenishing the French military’s equipment and helping it obtain more recruits by giving young people a taste of military life.

The U.K. under Prime Minister Theresa May hasn’t been as gung-ho. Last month, May asked Williamson to justify a continued U.K. role as a “Tier One” military power alongside the U.S., Russia, China and France, asking whether the country shouldn’t concentrate instead on issues such as cyberwarfare. And though the U.K. isn’t, strictly speaking, a military power of the same magnitude as the U.S., Russia or China, the lack of ambition is troubling to the U.S. as the leader of NATO.

The question is, however, whether Macron’s relative expansionism is meant to please the Trump administration and push the U.K. aside as a “special partner” to the U.S. The French leader has been pushing for a stronger European Union military capability. Even if an EU military has not been portrayed as an alternative to NATO, it’s difficult to see it as anything but insurance against U.S. isolationism. The more Trump questions U.S. alliances and demands that Europeans follow his orders on trade, the military, international treaties and anything else that comes to mind, the more France’s increased attention to its defense will look like a counterbalancing strategy.

Thanks to Brexit, the U.K. is guaranteed not to play a leading role in such alternative arrangements. To the extent that Trump’s U.S. needs long-term allies, rather than just situational ones, it’s stuck with the U.K. in Europe. Though Mattis’s letter is worrying to May and adds to all the political pressure she faces, she shouldn’t worry too much or rush to increase the military budget. Even if NATO as a group starts losing its importance because of U.S. doubts about members’ commitment, the “special relationship” probably isn’t going anywhere.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Philip Gray at philipgray@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.