Harvard Is Doing America’s Best Students No Favors

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The evidence that Harvard University discriminates against Asian-American applicants seems clear. A lawsuit against the university uncovered evidence that admissions officers tend to rank Asian-Americans much lower than whites on so-called personality measures, despite alumni interviewers ranking them similarly. This clearly seems to reflect the negative and inaccurate stereotype of Asian-Americans as, in the words of writer Wesley Yang, “textureless math grinds.” Meanwhile, schools with explicitly color-blind admissions, such as the California Institute of Technology, admit many more Asian applicants and a lot fewer whites.

Harvard’s defenders, meanwhile, are not necessarily racist — many fear that a court-ruling against anti-Asian discrimination could open the door to a general repudiation of race-based affirmative-action policies, which would then hurt black Americans and other underprivileged minorities. Indeed, this does seem to be a part of the motive of the group that brought the lawsuit.

But the focus on fairness in Harvard admissions misses — and may even distract from — a number of much larger issues. One is that the job market is funneling many top graduates into jobs where their talents are wasted or misused. But a second problem is that elite schools like Harvard are simply not providing the educational value to the country that they could be providing.

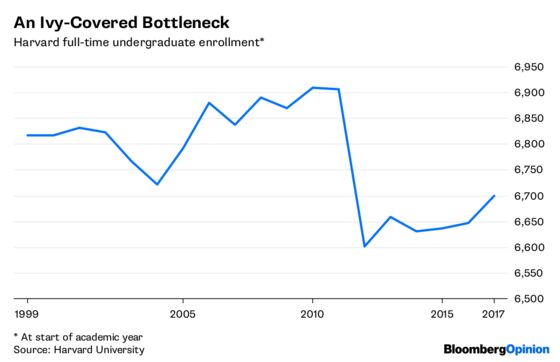

During the past two decades, Harvard hasn’t increased the size of its student body — if anything, it’s decreased:

This has happened even as the number of applicants has soared. Not only are more international students applying to — and getting into — the best U.S. private universities, but better information technology has allowed more Americans to apply as well. The result is that Harvard’s admission rate has fallen from about 12 percent at the turn of the century to about 5 percent today. Other elite private schools are little better.

As a result of low and ever-falling acceptance rates, American high-school students endure an ever more punishing rat race to try to get into top private schools. The marathon of standardized tests, advanced-placement tests, extracurricular activities and so on was already exhausting when I was a high-school student two decades ago, and must be much worse now. In this environment, it’s utterly unsurprising that people are fighting about racial bias in the admissions process — put people in a pressure cooker and tell them to compete, and they usually will do so. Elite American kids must increasingly feel like participants in the “Hunger Games.”

But because Harvard & Co. isn’t actually educating more undergraduates, much of this effort isn’t serving a useful social purpose. If you believe — as I do — that a college education is more about building skills, knowledge and perspective than simply signaling your ability to future employers, then it should be clear that the country’s finest colleges could be doing a much better job.

If Harvard can give 7,000 undergraduates a top-notch education, why not 14,000? Sure, it would have to hire more professors to keep class sizes down, build more dormitories, increase spending on student-life activities and various facilities. But Harvard has already paid many of its fixed costs, including creating a valuable brand and setting up most of its key institutions. And some student resources, such as public spaces, could be used by more students without overcrowding (this is even more true of universities like Stanford that have large amounts of land).

And there are plenty of applicants out there who are perfectly qualified for the elite schools that don't admit them. These colleges routinely reject large numbers of students with perfect test scores. Some of those are international applicants, but many are highly qualified Americans.

Meanwhile, Harvard has plenty of money to spend. Its endowment has risen from $5 billion in 1990 to more than $35 billion in 2017. What is Harvard doing with all that money, if not to further its stated mission “to educate the citizens and citizen-leaders for our society”?

The unfortunate truth may be that Harvard’s true goal isn’t exactly what its mission statement claims. Instead, it seems likely that Harvard’s administrators want to maximize the school’s status. In order to make Harvard as exclusive as possible, it makes sense to restrict the student body size and lower the acceptance rate. That maximizes Harvard’s position in prestige rankings like the ones produced by U.S. News & World Report, and helps maintain the mystique that gets Harvard alumni hired for top jobs. Meanwhile, all the schools lower down in the rankings are trying to catch up with Harvard and the other Ivy League schools, giving them an incentive to restrict their own class sizes.

This is wasteful. If all the most selective schools together made a pact to increase their class sizes, they could do a lot more for American education while keeping their prestige intact. But this is a classic coordination problem — no school wants to be the first to increase enrollment. Often, this kind of problem can be partially solved by government action — as when state governments mandate that top state universities serve a broad range of students. But private schools are not subject to government fiat.

Thus, universities such as Harvard end up boosting their own reputations at the expense of American education, embroiling the nation’s youth in a counterproductive, stressful, bitter rat race in the process. The system is broken, and it may only be fixed when some elite universities decide to do the right thing, and admit more students.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.