(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The hotel where I stayed in London last week has a restaurant that specializes in poke, the Hawaiian dish featuring chunks of raw fish atop of a bed of rice and vegetables. A couple of blocks away, in the restaurant arcade under the new Bloomberg building, I encountered a branch of Ahi Poke, a five-location London chain.

I first ate poke in Los Angeles in the summer of 2015, as it took Southern California by storm. Not long afterward, it conquered New York. By late 2016, Nation’s Restaurant News was proclaiming that “poke is sweeping the nation.” Now it appears to be sweeping yet another nation.

And so, as I consumed an Oahu bowl at Ahi Poke one day last week, I started wondering whether there are enough fish in the sea to survive this globalization of poke. I am not the first to wonder this. LA Weekly ran an April Fools’ spoof last year headlined “L.A. Poke Joints Shutter as Ocean Officially Runs Out of Fish.” Hawaii-based journalist Jennifer Fiedler took a more serious look in an extensively reported 2016 article for New York magazine’s Grub Street site, although she wasn’t able to answer the question definitively. I won’t be able to answer it definitively, either, but I can at least take a couple more steps in that direction, plus share some cool charts.

The main fish of concern here is the yellowfin tuna (scientific name: Thunnus albacares), which is almost certainly what was in my Oahu bowl. Poke restaurants outside of Hawaii also serve a lot of raw salmon, but the overwhelming majority of commercially available salmon is farmed, and while there are environmental concerns about some salmon-farming practices, we do not seem to be in any danger of running out of the fishies.

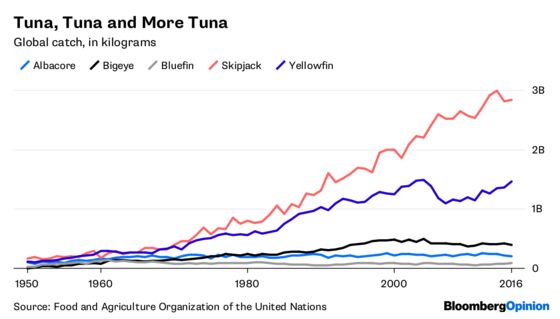

The quintessential poke fish, though, is ahi tuna, and it’s all wild-caught. In Hawaii, ahi originally meant bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus), but yellowfin now gets the name, too. With the global yellowfin catch almost four times bigger than the bigeye catch, and the price lower, the ahi you eat in your poke is generally going to be yellowfin.

The most abundant tuna, skipjack (Katsuwonus pelamis), isn’t technically tuna but is related, and it has become the mainstay of the tuna-canning industry. Albacore (Thunnus alalunga) was the original mainstay of the tuna-canning industry when it was established in Southern California in the early 1900s, and it is still what you get in “white meat” tuna cans. Something upward of 60 percent of the global tuna catch ends up in cans or other shelf-stable packaging, and Thailand is the biggest packager, with about a 40 percent global market share. The U.S. used to be No. 1, but concerns about dolphins (more on that in a moment) and a search for lower labor costs brought an exodus starting in the 1970s. It remains the No. 1 consumer market, with the European Union, Japan, Australia and Egypt (!) also big.

When it comes to fresh and frozen tuna, Japan created the global market for it and continues to consume about 60 percent of it, although demand has been ebbing as the population ages and shrinks. Bluefin, of which there are three regional species, is the favorite of Japanese sashimi and sushi aficionados, fetches by far the highest prices, and has been in short supply for a long time. It is the one kind of tuna that is farmed in significant quantities, although in this case farming (some call it ranching) means catching wild bluefin and keeping them in floating cages where they are fattened up until their belly flesh can be sold in Japan as high-priced toro. A lot of bigeye tuna end up in Japanese sushi restaurants, too. So do a lot of yellowfin tuna, but there are more than enough left over for the rest of us. Which means that, if you’re eating raw or freshly cooked tuna outside of Japan, that’s usually what it is.

The above summary of the tuna market is gleaned partly from United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization reports and databases, partly from reports by various global fisheries organizations, and partly from a conversation with Bill Fox, a three-decade veteran of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Marine Fisheries Service who is now vice president of fisheries at the World Wildlife Fund (and is not, as best we could determine, a relative of mine).

When I shared my concern that the globalization of poke might kill off the yellowfin, Fox — who lives in Southern California and eats poke on a regular basis — offered reassuring words. “I suspect it's some of the lower-grade yellowfin that doesn't make the cut for high-end sushi,” he said. “It's part of the saving-the-waste equation.” A little later, he added, “There's always a concern when there's a new commodity that's very high-priced because that tends to promote overfishing, but poke seems to be coming from the lower end.”

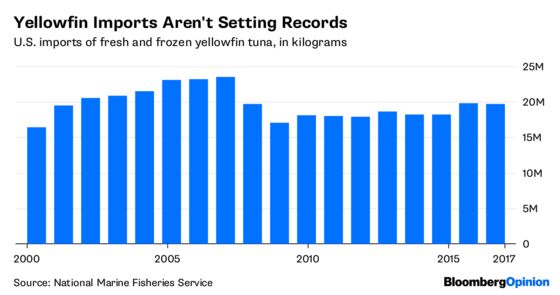

There is certainly not much indication in the data that poke fever has led to an unsustainable rise in yellowfin tuna consumption here in the U.S. Yes, imports of fresh and frozen yellowfin did jump 8.6 percent in 2016, but they were still well below mid-2000s levels. In 2017, they fell slightly, and in the first four months of 2018, they fell again.

I focus on imports because, while U.S. fishing boats brought in more than 100 million kilograms of yellowfin a year during the 1970s, the domestic catch in 2016 amounted to just 3.7 million kilograms, most of it caught off Hawaii.

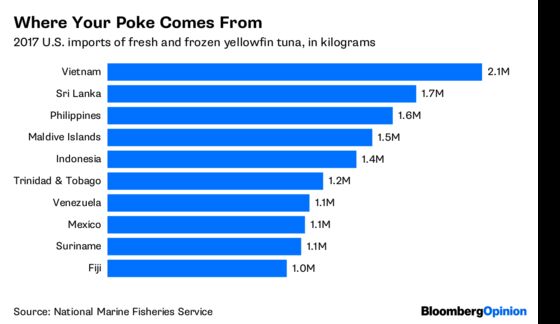

A big part of the original idea and appeal of poke in Hawaii was that you were eating scraps of fresh-off-the-boat fish caught by locals, but marine ecologist Rick MacPherson wrote last year that even in Hawaii, “mass-market poke retailers are sourcing deep-frozen tuna (often treated with carbon monoxide gas in order to retain color) that were caught perhaps months ago by tuna longline fishermen, often from the waters of Micronesia or the Marshall Islands.” On the mainland, the tuna often comes from even farther afield than that. These were the top sources of U.S. fresh and frozen yellowfin tuna imports in 2017:

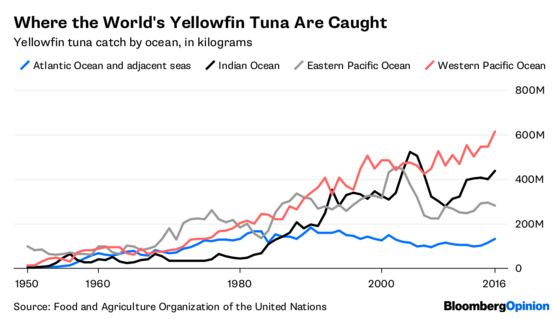

The Western Pacific and the Indian Ocean have become the leading yellowfin tuna fisheries worldwide.

The Western Pacific borders the Far East, and the Eastern Pacific borders the West Coast of the Americas. The Hawaiian Islands are in the western third of the Eastern Pacific. This can all be a little hard to get one’s head around at first, but you get used to it.

The Eastern Pacific is where industrial-scale tuna fishing began, and also where the first big tuna sustainability crisis occurred — in the 1970s, as alarm grew over the hundreds of thousands of dolphins killed every year in purse-seine nets used by tuna fishermen. A variety of mitigation techniques have brought that number down to the thousands or possibly lower, Fox said. Also, dolphins only swim with the tuna in large numbers in the Eastern Pacific, so this isn’t a problem anywhere else. Other forms of bycatch are an issue, with sea turtles, birds, sharks and all manner of other marine life getting caught in the purse seines used for about 60 percent of the global yellowfin catch and on the hook-studded longlines that are the next-most-common gear. And while the phrase “highly fecund” comes up a lot in scientific discussions of the yellowfin tuna, indications are that it hasn’t been fecund enough to avert past overfishing in the Eastern Pacific and Atlantic, and current overfishing in Indian Ocean.

On the bright side, I know about those indications because there’s an organization keeping an eye on them that actually seems to have some clout. The creation of the International Seafood Sustainability Foundation in 2009 was spearheaded by Chris Lischewski, then the chief executive officer of San Diego-based Bumble Bee Foods, who roped in StarKist, Chicken of the Sea and other big canned-tuna brands and turned to the World Wildlife Fund for help. The ISSF puts out detailed annual reports on the “Status of the World Fisheries for Tuna,” monitors its member companies for compliance with sustainability measures, and lobbies regional tuna-fishery bodies to implement even tougher measures. It is also planning to start monitoring labor conditions on tuna boats. The big-business nature of the tuna industry, not just in canning but on the fishing side, too — tuna purse-seining is dominated by only about 800 big boats, according to Fox — makes coordination of conservation and other efforts easier.

This ability to coordinate may not always be for the best: Lischewski stepped down as Bumble Bee’s CEO last month after being indicted by a federal grand jury for price-fixing. And any seafood conservation efforts run up against the barrier that, as Canadian authorities learned last year after they relaxed restrictions on cod fishing because they thought stocks had recovered enough (narrator’s voice: They hadn’t), human knowledge of piscine affairs remains limited. Still, within the bounds of current knowledge, it does seem correct to say that it’s OK to go ahead and eat a bowl of poke.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brooke Sample at bsample1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.