(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It’s been a tough few months for the euro zone. In Italy, a populist government has reignited fears of a breakup of the currency union. Angela Merkel has poured cold water on the federalist dreams of Emmanuel Macron. The economy shows signs of slowing, and there are fears that a trade war could knock the recovery completely off course.

And yet. Comments at the weekend from two of the bloc’s most important finance ministers — Italy’s Giovanni Tria and Germany’s Olaf Scholz — show maybe not all hope is lost. Scholz said he was more optimistic than many of his countrymen about Italy’s new populist government behaving itself fiscally. Tria backed him up by saying: “We don’t want to boost growth via deficit spending.” If Berlin and Rome can maintain this surprisingly level-headed approach toward each other, maybe there’s room for a little Macron-style positivity after all.

These are the kind of comments one would expect from finance ministers, of course, but anything that might help repair the fractious relationship between the two countries is welcome. They’ve been at loggerheads since the creation of the euro zone and the divergence of their economies. Italy’s national output per head stood at 81 percent of Germany’s in 1999, the year the euro was introduced. It’s 72 percent now — and falling.

In Germany, Italy is seen to have squandered the steep drop in interest rates that followed the euro’s creation. And it’s true, Italy should have cut its public debt and boosted its competitiveness more than it did. Berlin fears Rome is after its money, as shown by its pursuit of more risk-sharing across the currency union.

Meanwhile, many Italian politicians see Germany as the euro’s big winner. Had Berlin stuck with the deutsche mark, its products would be less competitive internationally. Rome officials say Germany was allowed to rescue its banks during the financial crisis, before the rules were changed so that others couldn’t. They accuse Berlin of paying lip service too to reforms that would strengthen the monetary union, for example by creating a common insurance for bank deposits. And all this while imposing draconian demands to cut risk — such as the insistence that bondholders pay toward bank rescues.

The election of an anti-establishment coalition in Italy has deepened the divide, especially after the Five Star Movement and League put together a wildly expensive list of tax and spending promises. German politicians, such as EU commissioner Gunther Oettinger, have warned that they are undeliverable — earning a sharp rebuke from the populists. Five Star and the League make no secret of their mistrust of Berlin. They say Italy’s national interest has been neglected after successive governments were too friendly with the Germans.

So Scholz’s interview with Der Spiegel was noteworthy and politically smart. “I believe the new Italian government will behave in accordance with the euro and Europe,” he said. “Much more so in any case than many people in Germany currently expect.” This may be wishful thinking, of course, but the message was markedly less antagonistic than previous noises from Berlin.

Even more refreshing was his support of new ideas to increase euro zone risk-sharing. He backed an unemployment reinsurance scheme, which would let struggling countries borrow from a common fund. It’s an idea that had already been aired by Merkel, and the fund would almost certainly be too small to make a huge difference to a crisis-hit economy. But tone is important here. Scholz is challenging the narrative that any risk-sharing goes against Germany’s interest.

Tria’s weekend comments certainly helped. A little-known academic who became Italy’s finance minister after the country’s president vetoed a Euroskeptic candidate, he used an interview with Corriere della Sera to quash most of the points in the League and Five Star’s big-spending coalition agreement.

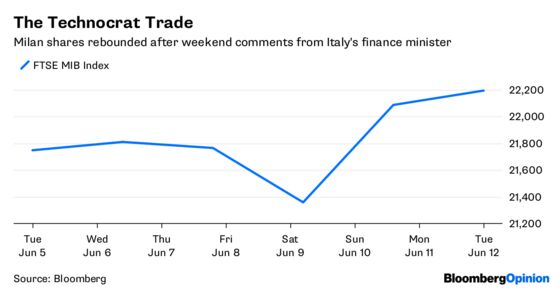

Investors cheered. Italy’s 10-year bond yields, which had skyrocketed after the wrangling over the new government’s creation, are now 2.77 percent, down from 3.11 percent on Friday. The Milan stock market has risen more than 3 percent in two days.

And there’s plenty to like in Tria’s statement. “It is not necessary to keep the public accounts in order and reduce public debt because Europe asks us to do it, but because we should not hurt the trust on our financial stability,” he told the newspaper. This contradicts the League and Five Star’s claims that the chief constraints on Italy were European institutions, including the European Central Bank. Tria says Italy wants to take responsibility for itself.

None of this means we should get carried away. The technocrat Tria will have to prove his mettle when he writes a budget in the autumn. Scholz is new to the job too, and his Social Democratic Party is the junior partner in a coalition with the more conservative CDU/CSU. The two ministers are merely reaffirming the official positions of their countries, rather than breaking genuinely new ground. Germany’s and Italy’s red lines — on cutting or sharing risk — still stand.

Yet at least they have sense enough to see that the sniping has to stop for the euro zone to survive. Tria and Scholz have offered some much-needed leadership. One can only hope that others follow.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.