(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The European Commission has settled a seven-year antitrust dispute with Gazprom, which was required to make concessions but avoided a fine. Although the Russian natural gas monopoly's detractors in Eastern Europe are likely to say Europe caved, the settlement announced Thursday shows that the company has been defanged and is no longer a threat to Europe’s energy security.

Margrethe Vestager, the European Union’s competition commissioner, has demanded billions of dollars in fines from U.S. tech companies such as Apple and Google. Some of Gazprom’s clients, including the Polish state-controlled oil and gas giant PGNiG, have lobbied for the Russian company to receive similar treatment. PGNiG and others argued that Gazprom should be punished for years of market abuse and that any compromises by the Russian company wouldn’t affect its ultimate goal of monopolizing the Central European gas market and projecting Russian power.

Instead, Vestager came up with a solution she says will be more useful to the energy market than a punitive move.

Gazprom has abandoned its attempts to ban customers from reselling its gas across borders, a practice many viewed as strong-arm coercion.

It's been clear since 2014, when Ukraine started buying Russian gas from Slovakia and the EU sided with Ukraine, that the tactic was doomed. But the settlement goes further: It forces Gazprom to make up for the lack of interconnector pipelines in Bulgaria and the three Baltic states by letting customers buy gas at lower prices set for other countries and have it delivered to these four nations.

Gazprom customers with long-term contracts now have the right to demand lower prices if they’re paying more than West European customers with competitive markets.

The Russian supplier has also agreed to a number of other conditions, including a waiver of any compensation for the cancellation of the South Stream project. The pipeline, which was supposed to carry gas from Russia to Austria via Bulgaria, Hungary and Slovenia, died a painful death in 2014 after the EU interfered to scupper construction deals.

In addition, Gazprom has agreed to eight years of close supervision by the EU, which will arbitrate any disputes. Vestager and her successors can fine the company up to 10 percent of its global revenue if it violates the settlement terms.

If Gazprom intended to monopolize the gas markets in Eastern and Central Europe, that goal is now out of reach. Eastern European countries are looking for new sources of natural gas. Poland and Lithuania, for example, are capable of receiving liquefied natural gas from the U.S. and other countries should Gazprom decide to cut supplies. With the settlement, that eventuality would be the only good reason for them to use the alternative supplies. Gazprom won’t be able to set higher prices than those established by market forces in Germany or Italy, where Russia is just one of several providers of natural gas.

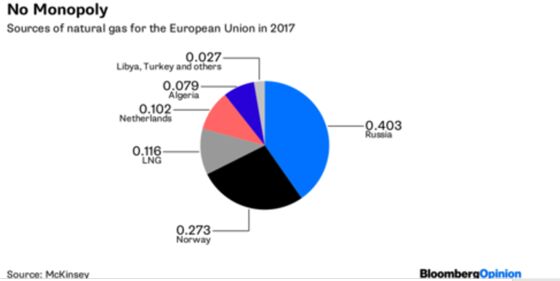

Theoretically, Gazprom could have a path toward a monopoly. Other sources -- primarily Dutch and Norwegian -- are beginning to succumb to a natural decline. But before Russia takes over on any serious scale, more resources could come online. Gas fields have been discovered in the Mediterranean. Any return to stability in the Middle East could contribute to Europe’s energy mix. The U.S. could, in time, provide cheaper LNG. Even today, energy from the U.S. is just 20 percent more expensive than Russian pipeline gas -- not enough of a differential for Gazprom to feel safe in the medium term.

At the same time, renewable energy sources, which generated a record 30 percent of EU electricity in 2017 (compared with 20 percent from gas), are bound to gain importance.

Gazprom’s situation is precarious: At any point, it could need its European customers more than they need it. The company’s executives understand they face a competitive and politically difficult environment in Europe. That requires them to play nice and offer prices that are difficult to undercut. It also makes supply disruptions highly unlikely, even for geopolitical reasons.

Then there are internal Russian politics. In 2017, Gazprom paid about 2.2 trillion rubles ($35.7 billion) in taxes, almost 2.3 percent of Russia’s gross domestic product. It’s also a major source of wealth for some of President Vladimir Putin’s close associates, who profit from infrastructure contracts. This cash cow’s viability depends on its ability to supply as much gas as possible to the European market, which accounted for more than 57 percent of revenue last year.

The EU has used this leverage intelligently to level the playing field. The settlement is arguably a bigger victory for Vestager than the fines on U.S. tech companies, which haven’t made dramatic changes to their practices and are suing the EU to reverse the rulings.

The settlement also provides evidence that it might make sense for both Germany and Russia to let the EU regulate Nord Stream 2, the pipeline into Germany that Gazprom has started building even though it lacks some necessary permits from Denmark and Sweden. The two countries have been reluctant to allow this because it would mean slow negotiations and potentially some tough conditions, especially concerning access to the pipeline for other suppliers, as well as curbs on Gazprom ownership. But the end result would likely work for everyone, except perhaps the U.S., which opposes Nord Stream 2 for both political and commercial reasons.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Max Berley at mberley@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.