What It Will Take to Finally Defeat Tuberculosis

(The Bloomberg View) -- Tuberculosis has been around since before recorded history, yet humanity is still struggling to get the upper hand. In recent decades, some strains have developed resistance to the strongest antibiotics known to medicine. While the number of deaths worldwide has been falling somewhat, TB killed 33 million people from 2000 to 2015, and still infects almost one-quarter of the human population.

So when world leaders say they want to end the epidemic by 2030, they are setting a tight deadline. Meeting it will require a global effort to uproot the disease from its most fertile breeding grounds, and get effective treatments and diagnostic tools to medical workers who need them.

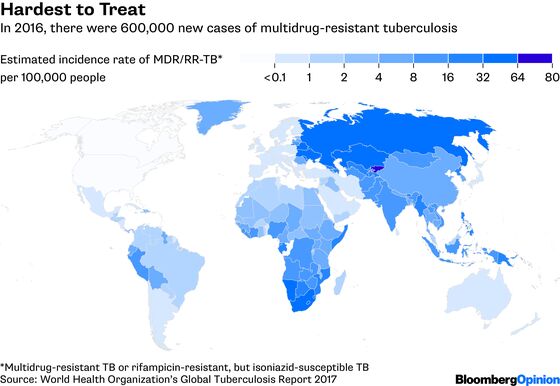

While TB leaves no country untouched, it is concentrated in just a handful of them. India, China, Indonesia and the Philippines accounted for half of the global incidence in 2016, whereas Europe and the Americas combined made up less than 6 percent. North Korea has the highest infection rate in the world for a country unaffected by widespread HIV, probably because more than 40 percent of its people are undernourished. As many as 8,000 multidrug-resistant TB infections may be occurring in that country each year.

The disease flourishes, in other words, where people are generally in poor health, for broad economic or social reasons. That’s especially true for the drug-resistant strains. Most of those who are infected with TB carry a dormant form of the bacteria, but when left untreated it can become active. It also easily spreads from anyone who coughs, sneezes, yells or otherwise expels bacteria-containing droplets. International travel and migration thus put every country at risk.

North Korea is a model of TB infection not only because its population is in poor health. The country also lacks modern diagnostic equipment, relying instead on 1930s-era X-ray machines that can detect disease only in the main organ afflicted — the lungs — and not in less common sites, such as the brain, kidneys or spine. X-rays also fail to distinguish drug-resistant infections. The country had a handful of modern GeneXpert machines, which do rapid molecular diagnosis, but lacked the required test cartridges and backup power systems. As a result, only a fraction of patients with drug-resistant TB have been started on the proper treatment. Medicine shortages, exacerbated by international economic sanctions, make it hard for doctors to do better.

In every country plagued by tuberculosis, investments in control can be extraordinarily cost-effective, returning $30 to $115 for every dollar spent. Not all efforts against the disease have to be expensive. Needed are simple videophones for remote patient consultations and inexpensive drug-susceptibility tests. Governments of TB-afflicted countries and the organizations that support them could also make better use of the tools they have. Many countries in possession of the new molecular testing machines are still unprepared to conduct more than one test per day.

The fight against TB must also address the health problems that cause dormant TB to become active, including HIV infection, malnutrition, smoking, alcohol overuse, indoor air pollution and diabetes.

Meanwhile, medical science needs to come up with quicker, safer and cheaper ways to diagnose TB, and a pipeline of new drugs to kill the bacteria and its resistant forms. Economic incentives for drug makers are essential, including cash awards for creating new last-resort antibiotics that, by design, would be used only rarely. A shortage of global funding for medical research — which has never exceeded a third of what’s required — explains why decades have gone by with no new TB treatments or vaccines. The good news is that a dozen vaccine candidates are now in clinical trials.

The world’s complacency about tuberculosis may be explained, in part, by the success of earlier battles against the disease. Control programs in the late 20th century led public-health officials to stop seeing TB as a leading threat. But history is clear about the consequences of inaction: Infections will multiply, millions more lives will be lost, and increasing antibiotic resistance will make it even costlier to stop this ancient foe.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.