What We Learned From a Year of Americans ‘Risking It’ Without Insurance

What We Learned From a Year of Americans ‘Risking It’ Without Insurance

(Bloomberg) -- For many Americans, 2018 was the year that health care reached a breaking point.

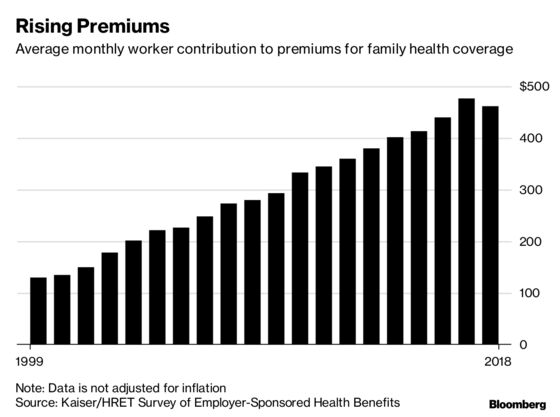

Insurance was still too expensive to buy. It didn’t cover nearly enough. And as the country’s politics festered, the government once again failed to solve the insurance conundrum, even as a large majority of Americans who flocked to voting booths said health care was their top concern.

My colleagues and I spent much of this year talking to people who had weighed the health benefits against the financial burden of purchasing insurance. Most decided to risk it, betting that going without made more sense than paying for coverage.

We started off following a dozen families: people who were trying to work, raise children and pay for a house or college. When we invited others to share their stories about going uninsured, an overwhelming number did — more than 5,000. Many sent us messages that could break your heart or raise your blood pressure.

In Virginia, the Jordan family shared their tale of sinking into bankruptcy because of unexpected medical expenses, even though they had insurance.

The Maldonados, in Texas, were forced to choose which members of their family to keep on insurance policies as costs ratcheted ever higher.

Others tried to find creative solutions, like the patchwork of alternatives to traditional coverage that the Bergevin family in Boise, Idaho, assembled. A nurse in South Carolina told us that she buys insurance every other year, getting screenings and care in even years and rolling the dice in odd years.

One theme that came up over and over again was that this is a problem reaching far higher into the economic spectrum than we first thought. Many of the more than 100 people we interviewed over the year had incomes of $100,000 or more. These were comfortable families, from outside. Yet, when they opened up their books to us, it became clear how much they needed to stretch to afford health care.

That often meant self-imposed health-care rationing. They didn’t make these decisions lightly. These weren’t uninsured-by-choice “young invincibles.” They weren’t reckless or ignorant — quite the opposite. Many were educated professionals, entrepreneurs and business owners. They had bad options and were forced to make a choice about which family “need” had to be downgraded to a “want.”

Some were more comfortable with the risks they were taking than others.

Keith and Diana Buchanan of North Carolina gave up their expensive health insurance this year, and bought a Bowflex exercise machine. Keith said he got into the best shape of his life: “A lot of it is a result of knowing that we’re going to have to take care of our own health a little better,” he said.

Others weren’t so lucky. In West Virginia, Tara Sullivan, didn’t go to the doctor until her flu turned into pneumonia. The drugs she needed cost $250. Among the more financially strapped of those we chronicled, she was able to buy her meds only by skipping a payment on her gas bill. The utility threatened to turn off her heat in the middle of winter.

“We don’t have enough money to go out to eat or take my grandchildren to the movies, much less pay for health insurance,” Sullivan told us.

We also talked to people who couldn’t afford to go without insurance — some of the 133 million people with pre-existing conditions who might have been shut out of insurance markets before the Affordable Care Act.

Andrea Preston in Bloomington, Indiana, lives with a rare autoimmune disease that causes her airway to collapse. At 38, she needs repeated surgeries to keep it open; she has already had seven and takes 15 medications. Preston has insurance through her job as a technical writer, but even then, her medical bills accumulate faster than she can pay them. “It’s a rolling ball I can’t get ahead of,” she said in an email. “It’s slowly steamrolling me.”

In Chicago, Joe Della Croce, a Vietnam veteran and two-time cancer survivor, should be retired at the age of 79. Instead, he holds down a low-wage job at a Home Depot to get insurance for his wife Rose, 61, who has multiple sclerosis. She’s too young to get on Medicare and can’t afford medication without insurance.

“It wasn’t what he had planned to do in his later years,” Rose said.

If 2018 was the year that health care fell apart, 2019 isn’t looking much better. On a Friday night in mid-December, a Texas judge ruled that the entire Affordable Care Act ought to be struck down. For millions of people who have coverage, whether they get to keep it may come down to yet another high-stakes legal drama as the case works its way through the court system.

Against that backdrop, the Democrats will take over the House of Representatives in January with ideas of their own. Some are pushing for an expanded role for government insurance such as Medicare for All. Though such proposals aren’t likely to pass a divided Congress, they’ll lay the groundwork for debate as Democrats vie for their party’s 2020 presidential nomination.

With a political fix as elusive as ever, large employers are signaling they are fed up with the current state of health insurance dysfunction. A three-way effort between JPMorgan Chase & Co., Amazon.com Inc. and Berkshire Hathaway Inc. is attempting to increase quality and deal with rising costs. Amazon and such other tech powers as Google parent Alphabet Inc. have begun to delve into pharmacy and health records. And a handful of startups are offering new ways to buy coverage and get care.

But those sorts of fixes are years away — if they ever happen. For the people we spoke with, that means more last-ditch compromises to cobble together a plan or stay healthy.

In Virginia, the Jordans’ deductible still isn’t affordable, and their bankruptcy proceeding will likely stretch into 2020. In Texas, the Maldonado family was able to buy coverage again for a college-age daughter and her mother Maribel, a cancer survivor. But, David, the father, is keeping himself off the policy for an additional year to save money. Tara Sullivan will be eligible for health coverage at a new job in Florida, starting in January.

But, at $200 a month, Sullivan doesn’t think she can afford it — so she'll remain in the ranks of Americans risking it, for yet another year.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Drew Armstrong at darmstrong17@bloomberg.net, Rick Schine

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.