The Power Grid Is Getting Bigger, But Plants Are Shrinking

The Power Grid Is Getting Bigger, But Plants Are Shrinking

The delivery of a gas turbine doesn’t normally make the news. But the Siemens 9000HL model that arrived last week to the Keadby2 combined-cycle power plant in the U.K. is something special. Weighing in at just under 1.1 million pounds (497,000 kilograms), it’ll rotate 3,000 times a minute and generate 593 megawatts of power at peak, likely for decades. It’s the pinnacle of today’s combustion technologies.

And—in Europe at least—it’s probably one of the last of its kind.

As Bloomberg News reporter Rachel Morison notes, natural gas was “long seen as a crucial bridging fuel in the energy transition,” a replacement for coal in the U.K. power mix and a backup for renewable energy generation. The challenge for gas, particularly in the U.K., is that coal has already almost vanished, and Keadby2 may not wind up pinch hitting for renewables at all. The future for gas looks instead like it will be dominated by a much larger number of much smaller peaker plants.

Combined-cycle plants run two turbines almost constantly. Peaker plants, which come online only during moments when demand for power threatens to outstrip supply, are simpler and designed to run less frequently, with faster startup times.

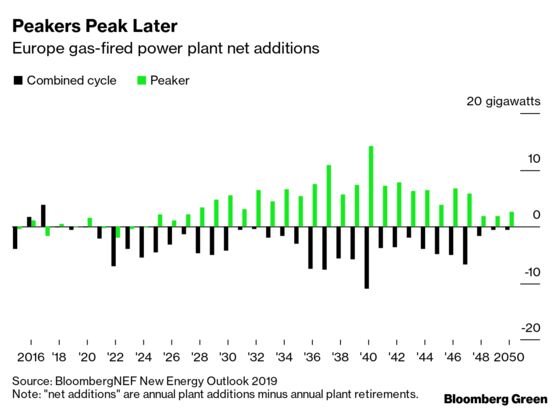

On a net additions basis—the total capacity of plants built in a given year minus the capacity that’s being retired—Europe’s combined-cycle gas fleet is already shrinking. New capacity is being built, but more old capacity is coming offline every year. Peaker plants have several decades of growth ahead, and their market doesn’t peak (pardon the pun) until 2040.

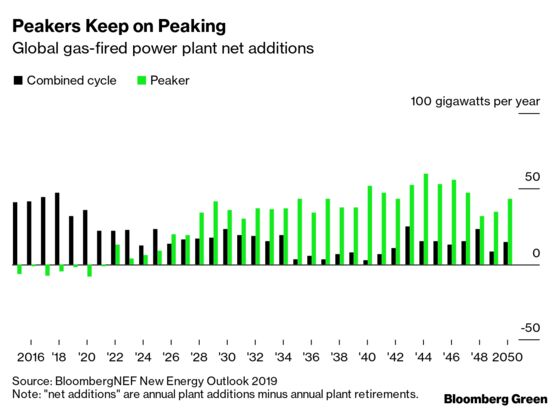

The global picture is a bit more balanced. Combined-cycle gas plants will meet growing electricity demand in many markets outside Europe, however by mid-decade they’ll constitute a smaller market than peaker plants in net addition terms. That will continue to taper off from the mid-2030s through 2050, according to BloombergNEF’s Energy Outlook 2019.

Power grids have to balance availability, cost, and price, and they do so via aggregations of assets that serve the common purpose of supplying consumers with energy on demand. As power technology changes, though, grids also reflect the tension between an older class of assets and a newer one.

All these power generation technologies—from a meticulously engineered gas turbine weighing 80% more than an Airbus A380 to solar power generators with less than a ten-thousandth the generating capacity—complement each other, but they compete on the margin. It’s not just a feud between renewable power and combined-cycle gas or coal, either; it’s also an evolving rivalry between batteries storing generated power and peaker gas plants that make them unnecessary.

One thing is clear in all this tension and competition: the marginal unit of power generation is coming from a smaller and smaller source. In 2020, the median kilowatt-hour generated in the U.K will come from a plant of 596 MW of capacity. In 2040, the median kilowatt-hour will come from a plant of only 40 MW of capacity.

Nathaniel Bullard is a BloombergNEF analyst who writes the Sparklines newsletter about the global transition to renewable energy.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.