The Forgotten Legend of Silicon Valley’s Flying Saucer Man

Alexander Weygers, a Renaissance man in the mold of the tech industry’s stated ideal, inspired an art dealer to become an acolyte.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- An idyllic ease permeates California’s Carmel Valley. Wealthy people have built ranch-style houses into the mountains, giving them views of the Pacific on one side and pine and cypress forests on the other. It’s neither too hot nor too cold, and the fresh ocean air makes you feel calm inside. These conditions, which give big ideas room to grow, have attracted artists to the area, as well as retirees who want to meditate on the good life. But every now and then, the gentle rhythm of this place gets disturbed. Someone’s perfectly manicured existence goes in a turbulent, unexpected direction.

For some people, it’s a real estate shock. For others, it’s an earthquake or—God knows—a wildfire. For Randy Hunter, a local art dealer, that moment arrived in 2008. The financial crisis had come to paradise. Artists and galleries accustomed to a steadyish stream of wealthy collectors fell on hard times. Things got bad enough that Larry Fischer, the owner of a sculpture foundry, decided to auction off pieces he’d held on to for years to help make ends meet. Ahead of the auction, he invited Hunter to come see if there was anything he liked. He guided his friend through the gritty warehouse toward a collection of bronze sculptures he thought might be of particular interest.

He chose well. The first sculpture Hunter saw, Up With Life, was a foot tall and depicted an adult’s face morphing vertically into a hand cradling an infant. Fischer explained that the sculpture, made by an unknown artist named Alexander Weygers after World War II, represented humanity rising up to find hope in the darkest of times. Its beauty overwhelmed Hunter, leaving him giddy and a little dazed. “I freaking started crying,” he later said. As he surveyed the room and saw one magnificent work after another, Hunter knew he had to have them. “I bought the whole collection of 30 Weygers statues.”

The sculptures came with an incredible story. Weygers spent close to half a century as the valley’s hidden da Vinci, crafting his home over the years from reclaimed wood and junkyard scrap metal, using tools he made on the premises. In separate workshops he produced sculptures, highly stylized photos, wood carvings, and home finishings. He also wrote books on blacksmithing and toolmaking and shared his talents firsthand with youngsters willing to camp on the property. He taught them to make their own tools, sculpt, and embrace his minimalist, recycling-centric philosophy. And amazingly, Weygers was a world-class engineer who in the late 1920s designed a flying saucer, a machine he called the Discopter.

Fischer had known Weygers well before the forgotten Renaissance man died in 1989, and his stories kept Hunter mesmerized for hours. “I was hooked,” said Hunter, who’d long pursued the art dealer’s dream of turning an obscure talent with a compelling background into a major figure among collectors. He’d buy up as much of Weygers’s work as possible, he decided, then bring the great man’s legacy to the world—and make a fortune.

Over the next decade, however, Hunter’s relationship with Weygers became far more complex than he could have imagined standing in that warehouse. As he spent countless hours researching the man, he began to see him as a symbol of a purer time in Silicon Valley. Weygers invented things because something inside him demanded it. The artist-engineer ran from fame and riches, focusing instead on hard work and ingenuity. The more Hunter learned about Weygers, the more he began to emulate and revere him, transforming from an opportunistic art dealer to an acolyte. Somewhere along the way, he decided to devote his life to telling Weygers’s story, even if it meant spending millions of dollars—and losing himself.

Hunter first emailed me in late 2015. I’d just published a biography of Elon Musk and was receiving scores of messages from people with free-energy machines, teleportation devices, and Mars landers who either thought they were the next Musk or wanted me to pass their brilliant ideas to the Tesla Inc. and SpaceX boss. At first glance, Hunter’s email seemed to fit squarely in the crazy pile. He promised to deliver “the greatest nonfiction story never written” about a genius artist who’d invented the flying saucer almost a century earlier. “I have been collecting his art, invention patents, photos, memorabilia, and artifacts, and interviewing all his family, friends and students,” he wrote.

I began searching the web for information about Weygers. There wasn’t much, but there was enough to show that Hunter might not be a total nutter. I responded politely but didn’t say yes to anything; he took that as an invitation to bound into my office in Palo Alto one day, carrying bags and cases.

Hunter was a tan, middle-aged man with a head of thick brown hair and dark glasses. What made him stand out was a powerful enthusiasm he seemed to be trying to keep in check for fear of scaring me off. Like any good salesman, he had an easy, convivial way about him that made you want to hear what he had to say.

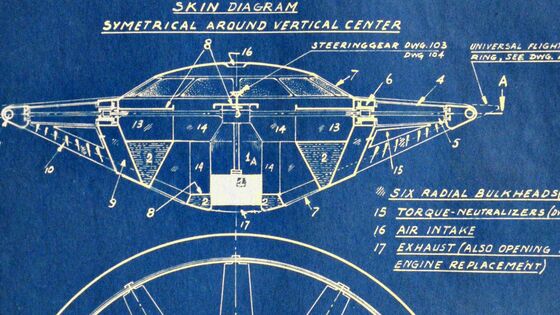

He reached into one bag and pulled out a poster that he unrolled on my desk. It was an elaborate drawing of a vehicle that looked like a more circular version of the Millennium Falcon from Star Wars. The idea was for the disk-shaped craft to take off vertically on jets of air. In flight the air could be directed forward or backward by a series of louvers in slanted positions, with all the steering done from a central cockpit.

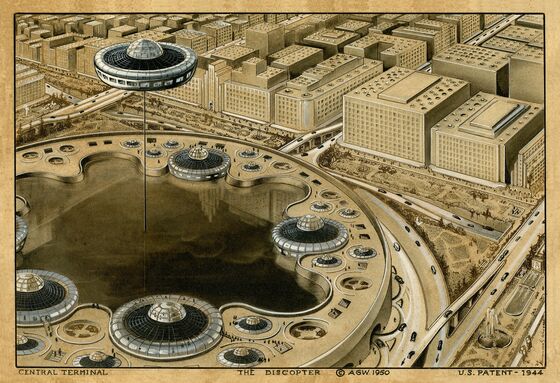

There were more drawings of the Discopter—lots more. The idea first came to Weygers in 1927; from the start he’d envisioned the machine transforming cities. Hunter’s next exhibit, a drawing that depicted how San Francisco might look in the faraway future of 1985, showed massive, transoceanic Discopters with rooms for hundreds of passengers moored at docks along the bay. Smaller commuter models, docked by the hundreds at office buildings, could detach carlike vehicles for getting around town. The drawings of the crafts’ interiors were remarkably ornate, showing everything from tennis courts and bunks down to a slice of cheese on a tiny sandwich.

Hunter and I talked for a long time. By this point, the strange tale had taken hold of me, too. I had to know more about this Weygers fellow. Where was he from? Did he try to build this thing? Why wasn’t he famous? I also wanted to know more about Hunter, including his motivations. He invited me to visit his gallery in Santa Cruz to check out the Weygers sculptures. As he left, he gave me some Discopter stickers, pamphlets about Weygers, and one of the posters, which he insisted I mail to Musk.

Hunter’s gallery was tucked down a side street in Santa Cruz, in a single-story industrial building behind a wall of cafes and surf shops. He said he had a “touch” of obsessive-compulsive disorder. The gallery showed a touch and a half.

Dozens of Weygers’s sculptures filled the main room: big ones on large black pedestals arranged symmetrically in the center, and smaller pieces ringing the edges. Glass displays held Weygers’s books, tools, and scale-model Discopters, and photos from his life dotted the walls. On a long table at one end of the room, dozens of folders meticulously cataloged information from Weygers’s life. There was a mathematical precision to the room, everything finely spaced and pristinely maintained, like a shrine. A small closet in the back had been turned into a UFO museum. There were hundreds of books (The Roswell Incident, Flying Saucers—Serious Business, Is Another World Watching?) and old magazines with some of the earliest mentions of flying saucers (Life, Reader’s Digest). Hunter spent hours on auction and collectors’ websites to snag as many copies as possible, like a UFO hoarder. The room was packed with UFO toys, beer, ray guns, DVDs, journals, and board games. “Thank god for EBay,” he said.

None of this really surprised the people who knew Hunter well. Born in 1958, he’d grown up in nearby Santa Clara back when Silicon Valley was still called the Valley of Heart’s Delight, after its bountiful fruit and nut orchards. As a kid, he spent weekends woodworking in his dad’s garage or going to flea markets with his mom. Even then, he collected things—Hot Wheels, coins, stamps, car parts, pins, guns. “The last name is Hunter, you know,” he said.

For the first decade of his professional life, Hunter worked at and then took over his father’s painting contracting business. A broken marriage sent him to Hawaii, where he began selling art at a high-end gallery on Maui. “In the first month, I was the No. 1 salesman,” he said. “I got lucky, hit a whale, and sold a couple hundred grand.” Soon after, he seized on the works of Robert Wyland, who’d become famous for his ocean-themed murals, and went on to sell millions of dollars of the art. “He was a hustler for sure,” Wyland says. “He always loved the arts and had a good eye.” Hunter grew his hair and beard long, enjoyed a joint and a surf on the beach in the evenings, and soaked it all in. “I was selling art, while a new batch of pretty tourist girls would arrive every Monday,” he said. “I loved it.”

When the internet took off in the 1990s, Hunter started gobbling up domain names tied to well-known artists and the arts in general. This helped him build markets for such sculptors as M.L. Snowden and Frank Eliscu, who produced the Heisman Trophy, and to sell to celebrity clients including George Foreman and Tanya Tucker. Hunter eventually returned to the Bay Area, running his websites and setting up the gallery in Santa Cruz. The art business did well, but it never offered him the fortune or fame of his dreams. “That’s been the personal challenge for me,” he said. “Can I take a guy that nobody has ever heard of and make him a national story?”

Weygers was born in 1901 on the Indonesian island of Java and grew up on a sugar plantation owned by his Dutch parents. The family also ran a hotel on the tropical property, a tangle of mango trees and sugar cane fields. Alex and his six brothers and sisters were home-schooled and ambled barefoot around the countryside dressed in white tunics. The family was well-off, but there was much to do to keep the farm and hotel running. Alex often helped out in the blacksmith studio.

At 15, he traveled to Holland for education at a prep school and then college. He studied mechanical engineering and naval architecture while continuing to hone his blacksmith skills. As part of his training, Weygers took long trips at sea and forged precise bits of machinery while bobbing around on the rough waters. “If parts wore out, there was no one there to save you,” he liked to say, according to an interview found in the vast trove of records dug up by Hunter. “You were alone at sea. You were expected to make and design their replacements with whatever was at hand.”

In 1926, Weygers moved with his young wife, Jacoba Hutter, to Seattle, where he pursued a career as a marine engineer and ship architect and began inking drawings of the Discopter in his notebook. By 1928, however, he’d fallen into a deep depression, after Hutter and the couple’s son died during childbirth. “This was the start of a downward spiral,” Weygers wrote to his parents after Hutter’s funeral. “Everything is so awful now.” He gave up shipbuilding and threw himself into sculpting, traveling throughout the U.S. and Europe to study under several masters of the period.

For a time, his work paid off. Shortly after he moved to Berkeley, Calif., in 1936, his pieces began to appear in the Oakland Museum of California and the Smithsonian American Art Museum. But when World War II began, the market dried up and Weygers began to struggle again. At 40, and by then a U.S. citizen, he joined the U.S. Army and served two years in an intelligence unit, translating messages written in Malay, Dutch, Italian, and German. By the time he received a discharge at the end of 1943, he was refocused on his old Discopter design, thinking it could replace the helicopter, which he considered “an unfinished piece of engineering.”

Weygers saw the Discopter as a way to help U.S. soldiers as well as his family in the Dutch Indies, many of whom had been put in concentration camps by Japanese troops. He imagined Discopters flying quietly behind enemy lines to perform rescue missions. After a short, unhappy stint at Northrop Aviation in Los Angeles, where he worried that his colleagues might steal the idea, Weygers moved to Carmel Valley with his second wife, Marian Gunnison. An Army buddy had bequeathed him several acres in his will, so, with gasoline rations still in effect, the couple motored 350 miles north in a 1928 Ford Model A retooled by Weygers to run on steam from burning wood and kerosene. They didn’t see another driver the whole way.

The legend of Alexander Weygers began to take shape on this hilly, wooded 3-acre plot. For months, he and Marian slept in a tent he’d built and stayed alive on dandelion soup and gopher stew. They managed to coax some bees into hives built with scrap lumber and traded the honey in town for other goods. “We were like Adam and Eve,” Marian later recalled. “We had no neighbors. It was so dark at night, and we’d just lie there and watch shooting star after shooting star.”

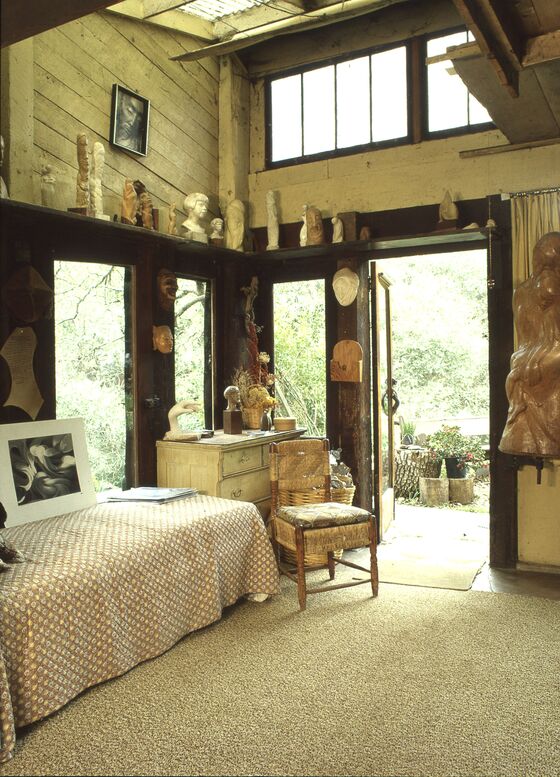

Eventually, Weygers set to work on a house that would become iconic. He foraged in dumps for logs, metal, bathtubs, sinks, and window frames to recycle. He began building a structure that looked like the cap of a mushroom—a hobbit’s lair in the Carmel Valley. It was circular, with curved sides. Weygers described it as a “geodesic dome gone wild.” Every hinge, handle, nut, and bolt he needed was forged by hand. He decided to leave the knotty wood exterior unfinished to match the landscape. A thick, flat roof covered the structure, and lichen took root along its edges. The end product blended into its surroundings, looking almost as if the forest itself had produced it.

Near the house, Weygers also built an art studio and a blacksmith shop. Then he created a darkroom underground for developing photos. The yard around these structures soon overflowed with scavenged objects. “It looked like a junkyard,” says Rob Talbott, who grew up nearby. “He had old vehicles, steel, wood, and wheels. He’d save anything, because he’d reuse it.” To that point, Weygers was known to turn auto springs into chisels, axles into hammers; a dentist’s chair became a contraption that let him raise and lower hunks of marble with the tap of his toe.

After settling in, Weygers turned back to the Discopter. The feds granted him Patent No. 2,377,835A in June 1945. He hoped to gift the patent to the U.S. military and then try to commercialize the technology. He assembled large binders of information about the Discopter and mailed them off to branches of the military, airplane makers, helicopter makers, and even carmakers to gauge interest. He received a handful of encouraging notes back, with engineers saying the vehicle appeared sound but too advanced for the time. (It would need lighter-weight materials and more efficient propulsion systems.) Most of the letters were disappointing. “Our technical people have reviewed this design and stated they have no interest,” one U.S. Air Force colonel wrote. “Your thoughtfulness in bringing this to the attention of the Air Force is appreciated.”

In 1947 a flurry of stories appeared in the popular press, discussing UFO sightings and carrying the flying saucer into mainstream consciousness. The Chicago Sun ran one in June of that year with the headline “Supersonic Flying Saucers Sighted By Idaho Pilot”; Newsweek and Life published pieces along these lines within a week of each other that July. There seemed to be a flying saucer outbreak across the U.S.

Tales of mysterious flying objects date to medieval times, and other inventors and artists had produced images of disk-shaped crafts. Henri Coanda, a Romanian inventor, even built a flying saucer in the 1930s that looked similar to what we now think of as the classic craft from outer space. Historians suspect that the designs of Coanda and Weygers, floating around in the public sphere, combined with the postwar interest in sci-fi technology to create an atmosphere that gave rise to a sudden influx of UFO sightings. Then, in the 1950s, NASA and other companies and organizations actually attempted to build vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) vehicles with saucerlike designs.

As all the talk of UFOs heated up and the military got serious about the craft, Weygers became convinced his designs had been stolen. The local press agreed with him. In April 1950, the San Francisco Chronicle ran one of the first stories about the Discopter with the headline “Carmel Valley Artist Patented Flying Saucer Five Years Ago: ‘Discopter’ May Be What People Have Seen Lately.” Rather matter-of-factly, the paper stated, “The invention became the prototype for all disk-shaped vertical take-off aircraft since built by the U.S. armed forces and private industry, both here and abroad.” Weygers sent a note to the U.S. Navy, accusing it of infringing on his patent, and he sent more letters to magazines and newspapers, asking them to correct articles about UFOs that failed to mention his invention. (Hunter managed to find much of this correspondence over the course of his decade of digging and indexed it all in his files.)

In interviews, Weygers said he knew the original Discopter designs lacked a viable power source for propulsion, but he felt that advances in lightweight materials and motors had arrived to make the device feasible. All he needed was someone to gamble on him with a few million dollars, and he could turn the Discopter into a reality. But as the years ticked by, he turned away from his invention and downplayed it. “With the Discopter, I reached the limit,” he told a reporter. “I invent something and then I go on. I still think someone could build it. Who really knows?”

These comments failed to capture the anger inside Weygers. The letters Hunter obtained dealing with the patent squabbles show a man who felt betrayed by the government he hoped to help. Weygers had never been one to focus on material possessions, but following the Discopter episode, he turned his abhorrence of money and objects into the basis of a fierce antigovernment philosophy. For the rest of his life, he tried to earn so little money from his work that he never had to pay taxes and feed into what he viewed as a corrupt, soul-killing system.

Following the flurry of attention in the early 1950s, Weygers went back to living a secluded life. Most of his time was spent working on the house or sculpting. He’d occasionally drop a sculpture off at a fair or exhibit so people could look at them, but he never stuck around to hear their comments or try to sell the work. “People who come out here and like a piece may buy it or they may not,” he told one reporter. “The hell with it. My artwork I do for the love of it.”

In the mid-’70s, Weygers published The Making of Tools and The Modern Blacksmith. The books, which included step-by-step drawings and guides, became surprise hits. So did Weygers: People from around the world began showing up at the house in Carmel Valley to learn from this man who seemed to come from a different time. He began charging a small fee for a six-week course in which students would learn how to scavenge for materials, make tools, and sculpt. He ran six fires at a time and had 14 anvils for people to work on as he performed demonstrations. The smells of burning coal, metal, and wood chips flowed through his blacksmith shop, which he kept dark so people could see the changes in the color of metal—yellow, blue, orange—as they worked it. Tall and thick, Weygers remained fit into his 70s with powerful, muscled forearms, and his personality matched this chiseled presence. He didn’t suffer fools or people unwilling to commit to the work.

Anywhere from six to a dozen students would show up per session, most of them in their 20s and 30s, and camp next to Weygers’s house. Each day at lunch, the students would gather around a kidney-shaped dining room table he’d fashioned from redwood and put on a swivel. Guests would take their seats, and Weygers would slide the giant table in front of them with a couple of fingers, showing off his engineering skills. The food came from Marian’s garden; the plates and utensils, from his forge. “It was a time when technology seemed to be accelerating,” says Joseph Stevens, a student who trekked to the property from Canada three times in the 1970s. “But when you were at their house, time really stood still. It could have been any time, any century even.”

Along with the blacksmithing and sculptures, Weygers would show off his wood engravings, some of which took months, and a technique he called artography, in which he’d take photos of an object through a droplet of water placed on the lens, then trace portions of the pictures in pencil to sharpen details. As with the books, the photos brought him some attention and money, but he still managed to stay mostly out of the public eye. “He wanted to be left alone to live his own life,” says Talbott, his former neighbor. “The neighbors would see this old truck come down the road with all of this stuff in it now and again, and that’s it. Frankly, most of them looked down at him.”

Weygers taught the classes until he was 83, at which point vision and heart problems got the best of him. “He had macular degeneration and couldn’t focus on things,” says André Balyon, a local artist and Weygers’s neighbor. “None of his students came by anymore. It was all very frustrating to him.” Weygers died in 1989 at 87. He’d hoped the crazy house and studio would be turned into a foundation with sculptors in residence willing to leave their best piece behind when they moved on. Marian, though, had tired of roughing it, and parceled the land out into lots she sold. The home was eventually torn down. The sale of the property netted her about $400,000, and she lived in the area until 2008, when she died at age 98.

In May 2016, Hunter discovered that some of the property where Weygers had lived had come up for sale. He and his partner, Cathy Thomas, paid $1.6 million for 1.6 acres of land and a four-bedroom craftsman home. The grounds still looked just as they had in Weygers’s heyday, full of trees, shrubs, and hills, and the house was tucked back from the road at the end of a long, winding driveway. Remnants of Weygers’s workshops and house could be found in the ground. “We are so lucky to have found the house,” Hunter said. “It’s a miracle.”

Over the course of the next 18 months, Hunter and I exchanged many notes about Weygers. Or rather, he sent me a constant stream of updates about things he’d discovered and his ambitious plans for the property. He was particularly excited by Silicon Valley’s recent interest in flying cars, with Google co-founder Larry Page and several startups funding efforts to develop VTOL vehicles. Finally, the technology needed to power something like the Discopter had arrived. The world had caught up to Weygers’s genius.

Hunter’s fascination with Weygers was both inspiring and frustrating. As a Silicon Valley history buff, I reveled in the story of this lone engineer who’d rejected the area’s money and hype and decided to make a go of it with just his own two hands. Weygers embodied so many of the things Silicon Valley techies celebrate today but fail to live up to: He was a conservationist, a maker, and a farm-to-table foodie without any of the self-congratulatory pomp or circumstance that now surrounds those ideas. He was authentic in ways that the Valley isn’t much anymore.

The frustration stemmed from Hunter’s struggle to make Weygers famous. Hunter was a great salesman, but no one wanted to take the time to hear a complicated story about an unconventional life. Weygers couldn’t be packaged on Instagram in a splashy suit or force-fed to people on Facebook. Still, Hunter kept at it. If anything, his notes about Weygers started to feel more urgent, especially in mid-2017.

Hindsight has made the reason for this clear. Unbeknown to me, Hunter, then 58, had been battling cancer for years, and the sickness had taken a turn for the worse as it spread throughout his body.

In July 2017, I made the 90-mile drive to see what Hunter had done with Weygers’s old place. The results were glorious.

Hunter had built what amounted to a Weygers museum. As you walked down a flight of stairs to the basement, you passed a series of giant Discopter photos. In the basement, Hunter had set up a couple of couches in the center of the room and surrounded them with Weygers’s sculptures. His collection of Weygers photos had been artfully arranged on the wall, showing a timeline of his life. Tools Hunter had obtained from Weygers’s students were encased behind glass like fine art pieces. “It’s almost become like a race in my mind, like someone else will find this stuff before I get there,” he said.

Off to the left of this main room, Hunter had built a small movie theater with a velvet rope he’d pull to the side so you could enter. If you had 20 minutes to spare, he’d show you the Weygers documentary he had commissioned and let you flip through the screenplay proposal he’d ginned up for a Hollywood blockbuster about the man. A pair of Weygers’s larger sculptures flanked the movie screen, and the lights overhead were custom UFO-shaped fixtures. At the back of the room was a desk that contained information on what he called the Weygers Program: a list of the sculptures, Discopter prints, and other art Hunter hoped to sell. The theater’s bathroom had more UFO memorabilia and artography photos; the metal stand holding up the sink had Weygers’s initials, AGW, forged into it.

To the right of the main room, Hunter had re-created his studio UFO collection, only this time it was bigger, grander, and packed with more objects. He’d located a miniature version of the Discopter that Weygers made and enclosed it under glass. Open any drawer in this room, or the living room, or the movie theater, and you’d find reams of papers about Weygers’s life, including letters, newspaper clippings, patent filings, correspondence with lawyers, Freedom of Information Act requests, and CIA record requests. Over the past decade, Hunter had tracked down many of Weygers’s students and family members and interviewed them all. He’d also managed to discover that Weygers had been keeping a secret: He had an illegitimate son born in 1935, whom Hunter found and befriended. “He looks exactly like his dad,” Hunter said. “He’s only ever seen a couple of photos of Alex, and I have hundreds that I’m going to share with him.”

As we toured the property, Hunter took me to the backyard, where he’d started construction on a 20-foot-wide, UFO-shaped fire pit. There were small bulldozers smoothing the land on the left edge of the property. This is where Weygers’s blacksmith shop had been, and Hunter was going to resurrect it. “I’m going to build a world-class sculpture garden, too,” he said. “And re-create the studio and put in a gift shop.” His grand plan at this point was to make a Weygers museum that people could visit. “I am the largest collector of this guy’s work, and I feel guilty just hoarding it,” he said. He hoped the wealthy residents and tourists in Carmel Valley would stop by, get hooked, and perhaps buy some sculptures. For those who couldn’t get to the property, he’d created a traveling roadshow with giant Discopter and sculpture displays that could be fitted along the walls of a trailer and brought to science and art fairs.

All told, Hunter figured he’d spent $2.8 million on his Weygers obsession. Almost all of that, though, came from his partner, Thomas, a finance manager for wealthy families. She had fretted about the extent of Hunter’s obsession but let him do his thing while trying to put some financial order around the Weygers habit. “Thank God, I have Cathy. Otherwise, I’d be broke,” Hunter said. He was aware people thought he might have gone a bit mad, but he remained convinced that the world just needed to hear about the artwork and the Discopter, then everything would take care of itself.

Hunter and I had only spent time together on and off over the course of two years, but we always got along well and enjoyed each other’s company. Since our first meeting in my office, I’d seen his pursuit of Weygers shift from a moneymaking venture to something different. At that point, he seemed to genuinely care most about the world knowing who this Weygers man was. As his cancer worsened, Hunter figured I was his best bet at making this happen, and he continued to keep the seriousness of his illness a secret from me because he didn’t want me to give up on the story.

Almost exactly a year ago, Thomas sent me a note, saying it was important that I get to the house. Hunter had battled different forms of cancer—lung, spine, and liver—and it now appeared he didn’t have long to live.

I returned to Carmel Valley, and Hunter greeted me outside of his Weygers rooms. In just a few weeks, he’d lost a lot of weight. His clothes hung off his body except around his belly, which was distended and full of air from the treatments and the illness. His liver had given out, and he’d turned yellow. His big, once-energetic eyes were sallow and haunting. But he didn’t dwell on any of that, because he’d located the old steam-powered car Weygers had once driven from Los Angeles to the valley. “F---, it’s amazing,” he said. “The car has come to me.”

We spent a couple of days together talking about Weygers for hours upon hours. I’d sit next to Hunter on a couch and he’d begin a story, get drowsy from painkillers, nod off for 10 minutes or so, then rouse himself and pick right back up where he’d left off. The stories were still all there, only muddled. Hunter struggled to find dates and the right sequences of events, his once-encyclopedic knowledge of Weygers reduced to an abstract feeling of what was true. He’d hang on to me as we walked around the property and kept talking about his plans. Now he wanted to create a nonprofit dedicated to Weygers that would fund science scholarships for kids. At one point, his shoes came untied, so I bent down to fix them, and there they were: an $800 pair of suede Gucci chukka boots with rainbow-colored UFOs on the side. “The price sure isn’t the Weygers way,” Hunter said. “But I had to have them.”

Late on our last night together, Hunter, filled with opiates, turned spacey and reflective. “I’ve had a couple dreams about meeting Alex,” he said. “One time was a really euphoric experience. I was laying in bed, just about falling asleep, and everything got kind of glowy, and I felt this presence. I got this flash of white light, and I was overtaken by this feeling. I just thought for sure it was Weygers. I accepted it and figured it was the spirit of Weygers telling me I’m doing the right thing, that he was grateful and that I should continue my mission.” Hunter died a few days later.

Hunter wanted a big party and had left Thomas detailed instructions on exactly what to do. His funeral was held in a San Jose church with a circular shape, like the Discopter. A couple of members of Weygers’s family turned up, as did a couple hundred more who knew Hunter. After his funeral, we all gravitated to a large ballroom nearby, where a band took the stage as people ate dinner. I sat with Thomas and Hunter’s mother, sister, brother, and friends. Just about everyone got up and danced. Thomas said she’d decided it was her turn to see the mission through and find some money to support the Weygers Foundation. “It’s what Randy wanted,” she said.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jeff Muskus at jmuskus@bloomberg.net, Max Chafkin

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.