Salmon Farmers Are Scanning Fish Faces to Fight Killer Lice

New technology will use facial recognition to build individual medical records for millions of fish.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Not even fish will be able to escape the onslaught of facial-recognition cameras.

Millions of Atlantic salmon could have their faces stored in digital databases to track their health and single out those posing threats to their marine surroundings.

And before you ask if fish have faces, they do: A company in Norway has developed a 3D scanner that can tell salmon apart based on the distinct pattern of spots around their eyes, mouth and gills.

Fish-farming giant Cermaq Group AS wants to roll out the technology at salmon pens along Norway’s fjord-etched coastline, betting it can prevent the spread of epidemics like sea lice that infect hundreds of millions of farmed fish and cost the global industry upwards of $1 billion each year.

“We can build a medical record for each individual fish,” said Harald Takle, the head researcher at Cermaq, one of the partners testing the system behind what it’s calling an iFarm. “This will be like a revolution.”

In a world where surveillance technology is being deployed everywhere from airports and stadiums to public schools and hotels and raising a plethora of privacy concerns, it’s perhaps inevitable that farms on land and at sea would find ways to exploit it to improve productivity.

Just this year, American agribusiness giant Cargill Inc. said it was working with an Irish tech start-up on a facial-recognition system to monitor cows so farmers can adjust feeding regimens to enhance milk production. Scanners will allow them to track food and water intake and even detect when females are having fertile days.

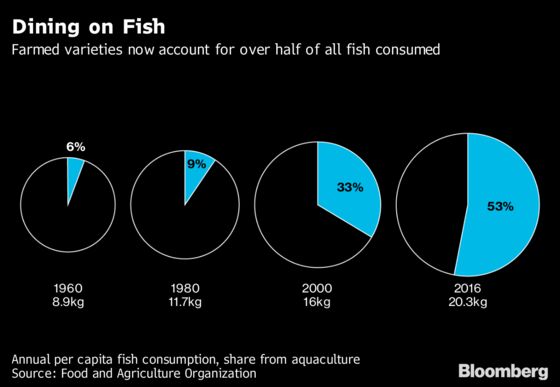

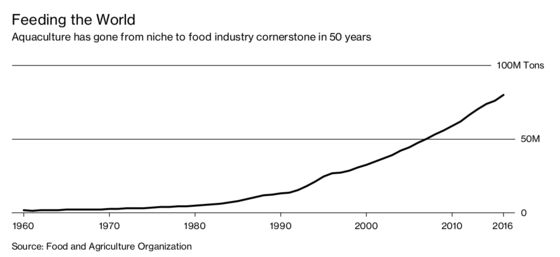

Salmon farming may be next in line. As fish vies with beef and chicken as the global protein food of choice, exporters like Norway, the world’s biggest producer of the pinkish-orange fish, have become the focal point for radical marine-farming methods designed to help the $232 billion aquaculture industry feed the world.

Cargill wants to apply facial recognition to aqua farms, and Cermaq, operator of over 200 salmon and trout farms in Norway, Canada and Chile, is already doing tests on the iFarm design with its Norwegian technology partner BioSort AS.

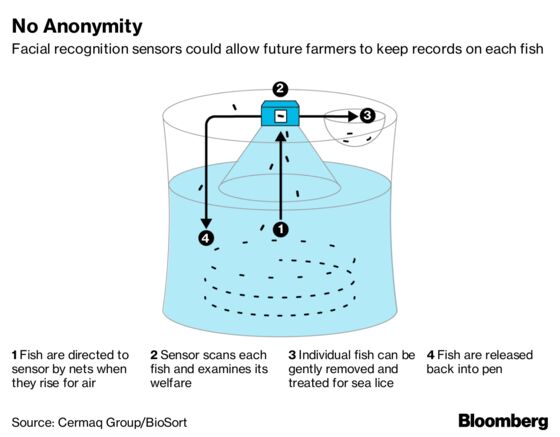

It’ll look a lot like existing fish farms, with networks of 160-meter (525-foot) circular nets that are typically 35 meters deep and home to up to 200,000 salmon. The difference is that iFarms would be equipped with camera scanners at the water surface. On any given day, about 40,000 salmon in each pen will rise to above water for a gulp of air, something their bladders need to regulate buoyancy.

Each time a salmon does this, typically every four days, it would go through a funnel fitted with sensors that would screen its face and body so records can be kept on each fish. If the machines pick up on abnormalities like lice or skin ulcers, the infected fish can be quarantined for medical treatment.

“Only the fish that actually need it will be sorted out for treatment, which means typically 5 to 20 percent,” said Geir Stang Hauge, 45, one of the inventors of the software and chief executive officer of start-up BioSort, based in Langhus, south of Oslo. “This avoids stressful treatment for all the healthy fish.”

He estimates detecting diseases early could cut mortality by 50 to 75 percent, which would be transformative for countries from Chile to Norway that have seen lice infestations impair salmon populations in recent years.

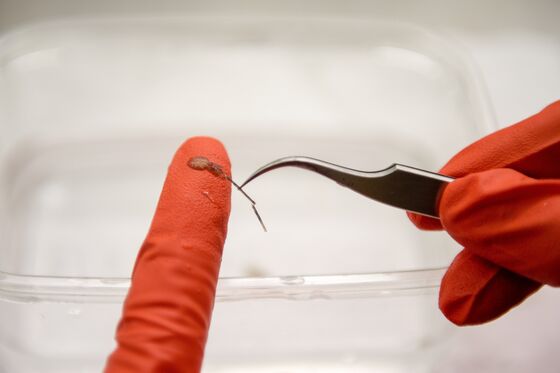

Parasitic sea lice have been around for eons, more recently thriving by feeding on Atlantic salmon’s mucus, skin and blood. They often render the fish unsellable due to the lesions they leave and have developed resistance to common chemical treatments. Even pesticide-free approaches—like quickly dunking salmon into barges full of warm water to kill the lice—are flawed because they don’t safeguard healthy fish.

“In most aquaculture, it’s the health barriers that limit growth,” said Einar Wathne, seafood leader for Cargill’s animal-nutrition unit, who’s been developing fish feed for 30 years. “Otherwise we could produce more, we could have sold more, we could have feed for more.”

Global marine farms supply more than half of the fish sold in supermarkets and served at restaurants, a figure that’s climbing fast because of the health benefits seen in pescatarian diets. But decades of growing salmon in farms at a breakneck speed is taking a toll. There aren’t enough smaller fish to feed them and wild salmon are exposed to diseases when farmed fish escape or young wild salmon pass by infested pens on their way to the open sea.

Hence the tens of millions going into research to, for instance, develop environmentally friendly fish feed made of insects and build farming pens in the open ocean where the fish will be less vulnerable to disease.

At a research facility in the village of Dirdal in southern Norway, Cargill scientists are even experimenting with a feed recipe containing an ingredient that changes the scent of the mucus salmon excrete in an attempt to trick lice so they don’t latch on.

“If we can add anything in the diet that can confuse the lice in any way, then we might prevent it from attaching,” said Renate Kvingedal, a scientist at Cargill Aqua Nutrition, who estimates the feed could reduce infection rates by up to half.

Whatever might be on the menu for fish in a few years time, Cermaq is betting it can start rolling out its futuristic salmon pens along Norway’s Atlantic coast in six years—but only if it gets the licences it needs from Norway's ministry of fisheries.

“We can control disease in a much better way than today,” said Takle, whose previous research showed that subjecting young salmon to aerobic exercise improved their resistance to illness once they were transferred to pens. “There’s a huge potential for transferring such technologies to farm other species as well.”

—With assistance by Deena Shanker and Hayley Warren

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Lynn Thomasson at lthomasson@bloomberg.net, Daliah MerzabanAlex Devine

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.