Pumping CO2 Deep Under the Sea Could Help Korea Hit Net Zero

When Donghae gas field closes next year, its pipeline to Ulsan could go into reverse, creating a major carbon-capture reservoir.

(Bloomberg) -- Thirty-six miles off the coast of South Korea, the Donghae gas field is running dry. When it closes next year, its pipeline to the port of Ulsan could go into reverse, creating the Asian nation’s first major carbon-capture reservoir by injecting CO2 into the rock below the sea bed.

The plan is to store 400,000 tons of carbon dioxide emissions annually for 30 years from 2025, according to Korea National Oil Corp., which will run a feasibility study on the project this year. It would be South Korea’s first major carbon capture and storage (CCS) project and could become one of the biggest in the world.

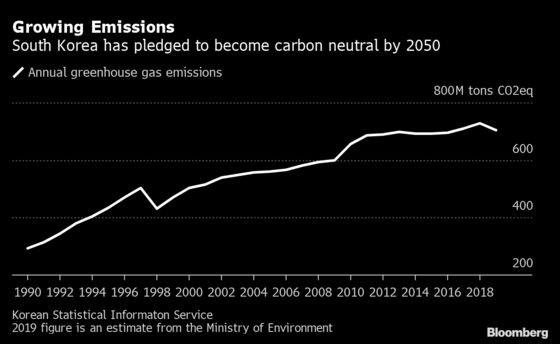

But it’s an expensive gamble. The idea of storing CO2 in depleted gas fields has long been a goal of oil companies and other industries looking for a way to offset their emissions as governments clamp down on polluters. But the costs have usually made it impractical. With South Korea committing to be carbon neutral by 2050, KNOC will use the empty reservoir to try to demonstrate that the system can work.

“Collecting and sequestrating CO2 will become an increasingly essential technology for us to reach carbon neutrality by 2050,” said Lee Hoseob, team leader at KNOC’s CCS department. “The viability of the project in the East Sea will prove that it can significantly lower the country’s carbon footprint.”

The worldwide installed capacity of CCS is only around 40 million tons per year as of 2020, according to the Global CCS Institute, which promotes deployment of the technology. The International Energy Agency said CCS will need to play a “major role” in a transition to net-zero emissions.

Developed nations including the U.S. and oil majors such as Exxon Mobil Corp. and Royal Dutch Shell Plc are proposing large-scale CCS projects as a way to offset emissions. President Joe Biden’s climate envoy John Kerry said there’s “enormous interest” in the technology, while Japan included it in the nation’s 2050 net-zero plan.

In November, the U.K. government announced a plan to invest £1 billion ($1.4 billion) to build four CCS hub-and-cluster projects to remove 10 million tons of CO2 by the end of the decade. In the U.S., Valero Energy Corp. and BlackRock Inc. plan to develop an industrial scale carbon-capture pipeline system and a storage chamber with an initial capacity of 5 million tons of CO2 a year.

South Korea’s plan helps “geotechnical stability” because pumping CO2 back into the subterranean rock strata would balance the loss of the extracted gas, said Kwon Yikyun, a geo-environmental sciences professor at Kongju National University, who’s working on the Donghae feasibility study. The technique has been used previously by the energy industry to force out crude oil or gas from reservoirs by pumping in CO2.

“Storing CO2 would actually help stabilize the pressure, so it’s a good place for the nation’s first CCS project,” said Kwon. The Donghae field was discovered in 1998.

The success of the project will determine the speed of investment and deployment across South Korea, which aims to have 4 million tons of annual CO2 storage capacity by 2023 in its continental shelf.

South Korea, the ninth-biggest greenhouse gas emitter, has less than 1% of the world’s population, but produces about 1.7% of its CO2 emissions. With its economy relying heavily on industries like steel and petrochemicals, experts say reaching net-zero by 2050 is a daunting task.

Repurposing an offshore gas platform has cost benefits as it could reuse existing underwater pipelines and cut out the expensive process of finding and developing an alternative site in the country. KNOC would gather CO2 from plants, including from the petrochemical and oil refining industries, at the other end of the pipeline in Ulsan.

Even with those advantages, the cost remains high. Carbon capture costs between $60 and $70 a ton, and needs to fall below $30 to allow the technology to become more widely adopted according to Ryu Ho-jung, a principal researcher at Korea Institute of Energy Research. Governments will need to help fund projects that involve private companies to prove the technology and lower the technical costs, said Kongju National University’s Kwon.

Turning old gas fields into carbon stores may make sense for a country with high levels of technical capacity, but it won’t be a “silver bullet,” said Terry van Gevelt, an assistant professor in environmental sustainability at the University of Hong Kong. It requires political will from the government and other stakeholders to become carbon neutral, he said.

Other challenges include ensuring the CO2 is transported and held securely, which means making sure the storage can resist earthquakes, geological fractures and leakage from old gas wells.

Skeptics say that those costs and challenges may continue to keep the system from becoming commercially viable.

“CCS is like a unicorn that will only live in our imagination because it has long been a costly and risky distraction,” said Kim Jiseok, a climate and energy specialist at Greenpeace in Seoul. “Focusing on expanding renewable energy will be a more efficient way of getting closer to carbon neutral.”

Also read: World’s Biggest Offshore Wind Farm Takes Shape in South Korea

But as governments raise penalties for companies that fail to curb or offset pollution, the cost equation is likely to change, making CCS more attractive.

“The main goal of CCS is to sequestrate carbon dioxide, but it’s also meant to stay economically competitive,” said Yoo Dongheon, a senior research fellow at Korea Energy Economics Institute. “It’s going to be an incredibly important technology in our race to net zero.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.