Profits Are Peaking for the World’s Most Lucrative Mobile Games

The Trailblazers For Mobile Games Have Peaked And Their Future Is One Of Steady Decline

(Bloomberg) -- More than a decade ago, Japan pioneered ways to profit from mobile games with a technique called gacha, which nudged players to spend lavishly on acquiring special characters or mighty weapons. Now developers, publishers and analysts say the trailblazers have peaked and their future is one of steady decline.

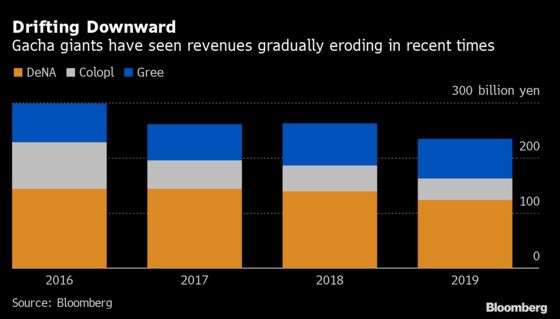

Gree Inc., one of the gacha innovators, is seeing in-game revenue fall, while rival DeNA Co. prepares to book its first fiscal-year net loss since going public in 2005. DeNA Chief Executive Officer Isao Moriyasu warned the company’s earning power from games “has weakened drastically.” Colopl Inc. said revenue in the most recent quarter was flat, suggesting its portfolio is slumping except for the mobile hit Dragon Quest Walk.

To blame is a mix of rising player expectations, higher costs to produce new content, aggressive overseas competition and some local complacency. Game companies are catering to existing, aging customers, having failed to effectively appeal to a younger generation or create profitable new breakthroughs.

“Japanese mobile game companies can’t give up the traditional gacha model because they still make some good money,” said analyst Hideki Yasuda of Ace Research Institute. “The decline is gradual, and that’s the major reason blocking the companies from making drastic reforms.”

Gree, DeNA and Colopl shares have dropped 10%, 14% and 24% respectively so far this year. DeNA slid to its lowest level in almost five years on Wednesday.

The name gacha comes from Japanese vending machines that offer prizes in opaque plastic capsules where the contents aren’t visible. In the digital version, players pay for a prize without knowing exactly which character, weapon or power they’ll find inside. Games are typically free to play, but spending on such extras makes titles lucrative for developers.

Gacha has the psychological pull of a Panini sticker album, where kids collect stickers to fill all the designated spots in a photo book for, say, football teams or hit movies. Game players spend small fortunes to snag rare items, motivated by bragging rights on social media or in-person gatherings.

The gacha genre still commands loyalty, having charmed a generation over two decades. Sony Corp.’s Fate/Grand Order is the world’s most lucrative mobile app -- of any type or genre, according to App Annie -- relying on the addiction-inducing mechanic of selling loot boxes that may contain prized characters or upgrades. The company’s Chief Financial Officer Hiroki Totoki recently said the number of active users hasn’t changed much, a common refrain from industry executives.

Colopl chief Naruatsu Baba last summer said the company was playing it safe with a new title developed for “people in their 30s and 40s,” hinting at the demographic targeted by his company. Colopl, Gree and DeNA all saw revenue slide last year.

Japanese game designers are slowing their pace of producing new loot -- because quality expectations have ballooned while their development teams have not. At the same time, gacha games are facing stiff competition for younger users’ attention, with App Annie data showing alternatives like Netflix gaining popularity.

The result: The same locked-in users habitually play their favored gacha games, waiting for new characters.

“There was a time when I would spend more than 500,000 yen ($4,500) a month,” said one local celebrity player of Fate/Grand Order, who uses the screen name Daigo and spoke on the condition his real name not be used. “But nowadays it’s much less, because the game isn’t getting new items to spend on. Recently, I spent less than 10,000 yen in a month.”

The hours spent in the game haven’t changed for Daigo, the player said, but he now finds himself spending a lot less each month.

When the gacha model was introduced to Japan in the 2000s, most people were still using basic feature phones. With only primitive graphics on board, the art requirements were low and developers were able to churn out dozens of new collectibles each month. Today, with high-resolution displays and powerful graphics chips in abundance, consumers expect paid items to have at least a 3-D model, along with added animations and voice packs.

“Companies can’t raise the gacha price as they are already expensive, but the cost to make new items continues to rise,” said Serkan Toto, a mobile games consultant. Most graphically-rich modern smartphone games are able to add only a few new items per month.

Part of the problem is integrating new characters with the legion of older ones, making sure not to upset players by devaluing the heroes they already paid for with a super-powered shiny new one.

At the same time, overseas competitors, such as China’s Lilith Games with its AFK Arena, are coming up with alternative monetization approaches and producing new content at a faster rate and at lower cost.

“As long as they keep the gacha style, speed will remain the key survival threat, and when it comes to speed, they can’t compete against U.S. or Chinese rivals as they have more resources,” Yasuda said.

Game companies may outsource production of artwork and sound to trim costs. But the important coding and quality-testing still has to be done in-house, meaning deploying new characters and eliminating bugs remains expensive.

Gacha game makers are “all locked in,” said Yasuda. “They are frogs boiling alive, very slowly.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Takashi Mochizuki in Tokyo at tmochizuki15@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Edwin Chan at echan273@bloomberg.net, Vlad Savov, Peter Elstrom

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.