Mapping ‘Whale Superhighways’ to Protect the Fertilizers of the Sea

Mapping ‘Whale Superhighways’ to Protect the Fertilizers of the Sea

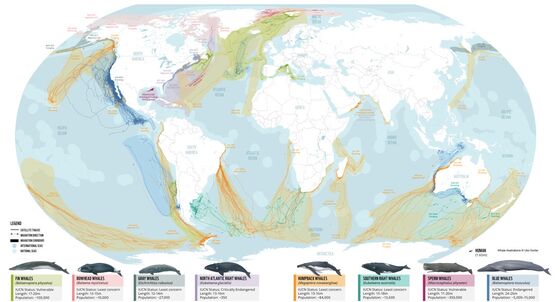

(Bloomberg) -- Scientists for the first time have mapped the world’s “whale superhighways,” the migratory routes the giant marine mammals follow as they traverse the globe.

Analyzing data generated by satellite tags attached to more than 1,000 whales, researchers plotted the cetaceans’ movements through what they call “blue corridors.” That allows scientists to pinpoint where whales, many of them endangered, are likely to cross paths with ships, fishing gear, plastic pollution and other deadly threats, according to the report released on Feb. 17 by environmental group WWF.

Protecting whales from those growing dangers is crucial, scientists say. Recent research shows that whales play a far larger role than thought in ocean health and the climate.

“Whales are important fertilizers of the sea, but also one whale captures the same amount of carbon as thousands of trees,” said marine scientist Chris Johnson, WWF’s global lead for whale and dolphin conservation in Australia and a report co-author. “When a whale dies, it takes a huge amount of carbon to the ocean floor and becomes a carbon sink.”

At the same time, scientists say, climate change and overfishing are reducing prey populations like krill. That’s altering whale migratory patterns, highlighting the importance of tracking their movements so policymakers can take action to preserve the animals.

“Some years there are tons of humpback whales really close to shore in Monterey Bay, and so people see all these whales from the beach and think everything is great,” said Ari Friedlaender, a co-author of the report and a professor of ocean sciences at the University of California, Santa Cruz. “But the fact is, the whales are close to shore because there’s no food anywhere else.”

Friedlaender participated in a study published in November 2021 that deployed satellite tags and drones to measure how much blue whales and other large whale species eat. They discovered that the whales consume a volume of prey two to three times higher than previously believed, a finding that indicates scientists had greatly underestimated whales’ contribution to ocean ecosystems and carbon sequestration.

Whale excrement spawns blooms of phytoplankton that produce half of the world’s oxygen and are the foundation of the marine food web. The scientists estimated that before industrial whaling exterminated two-thirds of the world’s large whales, the marine mammals in Antarctica annually ate more than twice the amount of sea food caught globally by humans today.

A 2019 report from the International Monetary Fund valued the environmental benefits provided by the existing population of whales at more than $1 trillion.

The migratory maps assembled by WWF from satellite tracking data provided by more than 50 research groups are designed to guide the conservation of whales and their role in helping regulate climate and ocean health. The data spans three decades, though most tracking information was collected over the past 10 to 15 years.

Daniel Palacios, an associate professor in whale habitats at Oregon State University, said the migratory maps bolster the case for the adoption of a proposed treaty to conserve the biodiversity of the high seas. The United Nations next week will convene to negotiate the terms of the treaty, which would protect the 58% of the ocean beyond national jurisdiction by creating marine preserves and requiring environmental impact assessments for potential harmful activities.

“The high seas are essentially a sort of Wild West, a no man’s land where anybody and everybody can do whatever they want, and we need to curb the impacts on whales from shipping and fisheries,” said Palacios, a report co-author.

The satellite tracking data shows that blue whales use the ocean off California like a Los Angeles freeway, constantly commuting up and down the coast. Government officials require ships to slow their speed in certain areas while scientists have developed technology that predicts in real time where blue whales are likely to be, based on ocean conditions, and alerts ship captains to their presence.

But the maps confirm that blue whales also venture into the high seas far outside regulated waters. There they are at particular risk from shipping traffic, which increased fourfold between 1992 and 2012, according to the report.

The high seas represent a gap in mapping efforts due the difficulty and cost of tagging whales far from shore. “There are many species and many areas where we haven’t been tagging,” said Palacios, noting that tracking deep-diving sperm whales poses a particular challenge.

That makes potential new threats to whales from industrial activities like seabed mining difficult to assess. The first area targeted for mining is a stretch of the Pacific Ocean between Hawaii and Mexico called the Clarion-Clipperton Zone. Although whales are known to pass through the region, it appears largely as a blank spot on the whale migratory maps.

“There are many areas that we still have not been to but that doesn’t mean there’s not whales there,” said Palacios.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.