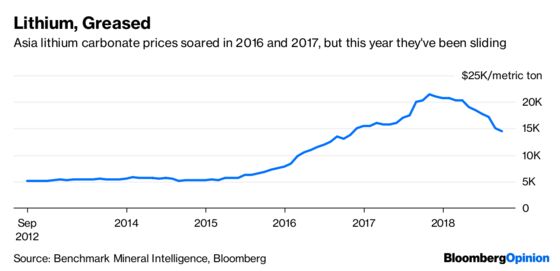

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- What ever happened to the lithium boom?

The electric-battery metal is trading at its lowest levels in two years. After doubling in 2016 and rising another third last year, lithium carbonate swap prices for Asia are down 30 percent so far this year, according to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence.

If that wasn’t bad enough, look at what just happened to Ganfeng Lithium Co., the world’s second-biggest producer. Its Hong Kong initial public offering has been priced at HK$16.50 a share, the company announced Wednesday, at the bottom of a target range that went as high as HK$26.50.

Even at those prices investors weren’t biting, with the slice available to Hong Kong investors about 40 percent undersubscribed. That’s arguably not surprising, given the run of IPO flops over the past year, including online car-sales platform Yixin Group Ltd. and smartphone maker Xiaomi Corp.

Still, it left a hefty share of the issue in the hands of LG Chem Ltd., Samsung SDI Co. and four Chinese state-linked companies who were acting as cornerstone investors and had subscribed for a fixed dollar amount, plus an additional 2 million shares which were placed with a unit of state-owned Guotai Junan International Holdings Ltd.

Valuations of lithium companies have been sliding all year, with enterprise value-to-Ebitda multiples on Albemarle Corp., FMC Corp. and Tianqi Lithium Corp. at about half their levels at the start of the year. That doesn’t explain all of the weakness, though: At the offer price, Ganfeng is valued at about 9.3 times 2017 Ebitda, compared with 10.3 at Albemarle and Tianqi and 17.9 at FMC.

The best explanation for this is the one we made back in May. Tianqi’s aggressive deal-making, plus the connections between the Chinese government and both its chairman and Ganfeng’s, make the lithium market look increasingly like a state-linked cartel.

Producers’ cartels ought to be good for the prices of the raw materials they sell, but that’s not really what’s happening here. China isn’t interested in lithium for its own sake, after all, but because it’s a key ingredient for the rechargeable-battery industry that Beijing wants to develop.

As such, the government aims to ensure ample supplies, which keeps prices low and maximizes the profits of the battery-makers and electric-vehicle companies it really cares about. Investors in lithium producers are typically counting on the opposite outcome: a situation where demand runs well ahead of supply and keeps prices high.

That would damage the margins of battery-makers, but allows those who dig up and dry out lithium compounds to make extraordinary profits.

New non-cornerstone investors will end up with less than 10 percent of Ganfeng’s share capital once the transaction completes. Chairman Li Liangbin, who’s on the ruling standing committee of the People’s Congress in Ganfeng’s hometown of Xinyu, will have 21 percent.

The company’s prospectus promises operational independence from its founder and largest shareholder, and by implication the government in which he’s a junior officer. But this is China in 2018. If a business in an industry of national importance wants to convince investors that it will always be on their side, rather than that of the state, it’s going to need a lot more than words on paper.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rachel Rosenthal at rrosenthal21@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.