Facebook’s Grip on Data Leaves Nonprofits Leery of Donate Button

Facebook’s fundraising products have generated $3 billion.

(Bloomberg) -- To most of the country, Duke was the obvious winner over the weekend when the college basketball powerhouse took down arch-rival North Carolina on a buzzer-beater in overtime.

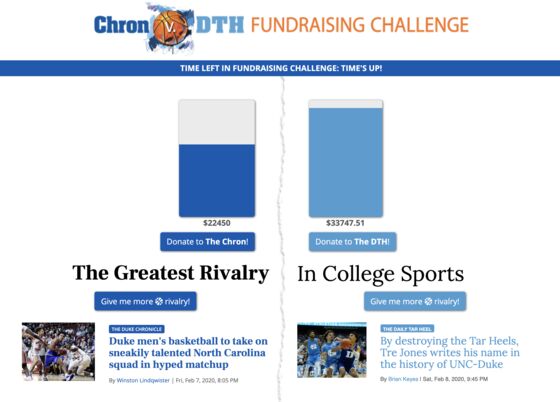

But the University of North Carolina scored a quieter victory: Its student newspaper, the Daily Tar Heel, beat Duke University’s Chronicle in an annual fundraising challenge, a multi-week affair tied to the game and intended to generate money for newsroom operations. Final score: Daily Tar Heel $33,747; Chronicle $22,450.

The whole affair left Chrissy Beck frustrated. Beck, the general manager of Duke’s Chronicle, thought she had an ace in the hole: a “donate” button on the newspaper’s Facebook page and Instagram profile. It was supposed to be a simple way to enlist the paper’s thousands of online followers, but Beck was stymied by a lengthy approval process. And even if she had gotten the go-ahead in plenty of time, nonprofits like hers have an even bigger gripe with using Facebook Inc. to raise money. While donors give lots of personal information to the social-media company, Facebook passes very little of that data back to the nonprofit.

“We want them to give next year, you know?” Beck said of donors. “And in order to do that, we need to know who they are.”

Facebook’s fundraising features, which have led to more than $3 billion in donations since 2015, are a way to generate goodwill for a company that struggles with its reputation among users, politicians and regulators. While the tools have the potential to help nonprofits reach a massive audience with minimal effort, they also come with some downsides, according to conversations with almost a dozen nonprofit groups.

Much of the frustration is about user data. Usually the social network is criticized for making too much information available. But this time, in a twist, some organizations say Facebook may be protecting the data a little too closely -- a sign the company’s complicated relationship with personal user data extends even to its feel-good features that don’t make any money.

By default, nonprofits only receive a donor’s name and donation amount, a virtually useless data set for fundraisers with a goal of building long-term relationships. The importance of following up with news and future fundraising opportunities means that email addresses, phone numbers, and physical mailing addresses are gold to nonprofits -- and almost none of that gold is available through Facebook’s donation system.

“Just like you hear in business where it costs less to keep a customer than get a new one, the same goes for donors to nonprofits,” said Rick Cohen, the chief operating officer at the National Council of Nonprofits.

Second Harvest, a food bank San Jose, California, uses Facebook for fundraising, but hasn’t made the social network a central part of its efforts, primarily because it can’t follow up with donors. Roughly two-thirds of Second Harvest’s revenue comes from individual givers, said Cat Cvengros, the group’s vice president of development and marketing, so those relationships are paramount. “We look at Facebook’s donate button as one more tool in our tool box,” she added. “We can’t rely on it entirely.”

A Facebook spokeswoman said the company weighs fundraising efforts with user privacy concerns. “We are always working to find the right balance to help nonprofits continue to make an impact, while making it easy for donors to both give to causes and choose how they want to stay connected,” she said in a statement.

Facebook offers two main ways for nonprofits to raise money. The first is a donate button that organizations can add to their Facebook or Instagram accounts. In other cases, users can start a fundraiser on behalf of a nonprofit. Lots of people do this on their birthdays, and ask their friends to donate in lieu of a gift. In both instances, Facebook doesn’t take any cut of the donation, or charge any fees -- a major benefit that many nonprofits mentioned.

The company’s greatest impact, though, is its scale. “The beauty of it is the ability to reach an audience that otherwise we would almost certainly have no budget and no facility to get in contact with,” said Chris Joseph, the communications manager at the League to Save Lake Tahoe, the nonprofit behind the “Keep Tahoe Blue” tagline. In just over a week in early January, for example, Facebook users donated more than $34 million to a single fundraiser set up for Australia’s wildfires. More than $1 billion has been donated thanks to birthday fundraising efforts alone.

“While it is a bit of a black hole in terms of data, the monetary benefit and what we’re able to do to truly impact lives with the dollars we raise outweighs the lack of data,” said Julie Winner, the managing director for social marketing and digital strategy at the American Cancer Society.

That’s not the case for all nonprofits, especially smaller ones without the brand recognition of a global organization. UNC’s Daily Tar Heel, which won the contest with Duke, rejected the idea of the donate button, worried they’d be asking donors to hand over important information to Facebook, a company that has mishandled that data in some high-profile incidents.

“It’s important from a strategic standpoint for us to have all the information that we need about the donors,” said Erica Perel, general manager at the Daily Tar Heel. “I don’t need Facebook or another company to have all the data.”

Laura Sherr, who runs digital fundraising at the Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito, California, just north of San Francisco, said her organization had serious discussions about the trade-offs of using Facebook for fundraising before jumping in aggressively 18 months ago.

“Yes it is different, and you don’t quite have the same access to [donors] as you’re used to, but it’s just a different kind of access,” Sherr said.

It’s the kind of transition that older, more traditional nonprofits are still making in an effort to compete for fundraising dollars in a digital culture.

At Duke, the Chronicle finally got approval for the donate button almost two months after initially applying, and just one day before the competition closed -- and a day after Bloomberg called Facebook about this story. “Working with Facebook to get anything like this done,” said Beck, “is absolutely aggravating.” A Facebook spokeswoman said the approval process can take six to eight weeks.

While the donate button didn’t help the Chronicle in its fundraising challenge this year, Beck said the potential reach means she’ll try to use Facebook next year. Could the donate button be the difference maker in topping the Daily Tar Heel?

“I hope so,” she said. “It certainly can’t hurt.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Kurt Wagner in San Francisco at kwagner71@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jillian Ward at jward56@bloomberg.net, Andrew Pollack, Anne VanderMey

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.