Ex-Cons Create ‘Instagram for Prisons,’ and Wardens Are Fine With That

Ex-Cons Create ‘Instagram for Prisons,’ and Wardens Are Fine With That

(Bloomberg) -- Laura Whitten, 35, woke up, rolled over and grabbed her phone, snapping a selfie in bed beside her dog. ‘Good morning, xo’ she wrote in a message to her boyfriend, uploading it to an app called Pigeonly.

The picture traveled from her home in the eastern suburbs of Charlotte, North Carolina, to a fulfillment center in downtown Las Vegas. There it was printed out, stuffed into an envelope and stamped with an address: Berlin Federal Correctional Institution, New Hampshire.

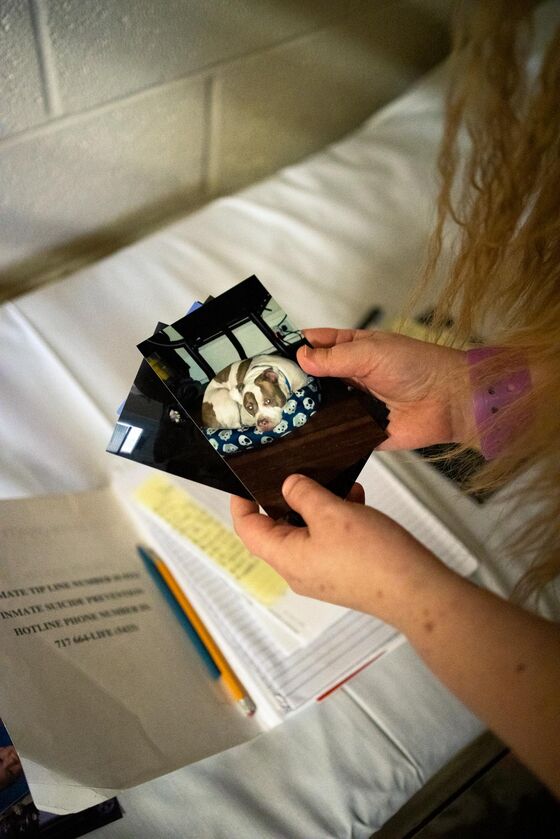

A week later, the photo arrived at the prison mail room, where clerks eyeballed it for drug paraphernalia and nudity, then delivered it to Inmate 20274-058.

Cedric Benton, 43, gazed at the image for hours, sitting cross-legged in a grey tracksuit on his bunk bed. Benton has six years left on a two-decade sentence for a drug-related conspiracy felony. Looking at the photo, he thought: “There is life for me outside these walls. I have to get out and stay out.”

Pigeonly is one of at least three apps—all launched by ex-cons—that are revolutionizing communications between prisoners and their loved ones. Even as the outside world has embraced texting, video chats and social media, U.S. prisons have largely remained technological dead zones, where inmates typically wait in line and pay to use antiquated computers running stripped-down email services. The trio of apps are slowly but surely disrupting a prison communications industry dominated by a handful of companies with little incentive to cut prices or boost services for the 2.3 million people behind bars.

Pigeonly and its ilk have hit on a communication model—a necessarily inelegant one—that meets inmates’ desire for a more tangible connection while serving the social-media habits of their loved ones. One of the apps, Flikshop, has been affectionately dubbed the “Instagram for prisons.” It’s an imperfect metaphor perhaps, but the app is the closest thing to the social network in prison, and Flikshop postcards are pinned up on cell walls across the U.S. Beyond giving prisoners an easier, cheaper and more fulfilling way to communicate, the men who started these apps also want to make inmates less likely to re-offend because they see there’s a life to be lived on the outside. Decades of research show that recidivism rates fall when prisoners are in regular contact with family. Criminal justice advocacy groups and rehabilitation non-profits have already started using the apps to make the prison population aware of their services.

Frederick Hutson, 34, started Pigeonly, Inc. in 2013, fresh from a five-year stint in federal prison for drug trafficking. “I saw first-hand how difficult and expensive it was to stay in touch,” Hutson says. “I also saw how much of an impact that made on the person behind bars. I would see the guys that had the financial means to stay in touch and when they left prison I would hear that they were doing well, but those who didn’t have the support network on the outside—I’d see them coming back in.”

Pigeonly—named for the pigeon post services of wartime fame—wants to become a bridge between those who live in a digital world and those who are imprisoned in an analog one. Customers subscribe to the app for a monthly fee, ranging from $7.99 to $19.99, in order to send photos and messages and have access to cheaper online phone rates. Pigeonly has 20 full-time staff, half of whom were previously incarcerated themselves. Every day, they send up to 4,000 mail orders into county, state and federal penitentiaries across the country.

Whitten says Pigeonly has helped her remain close to Benton even as he was bounced around prisons from California to New Hampshire. She pays $7.99 a month to access cheaper state phone rates and send unlimited photos and messages. “I send him pictures all the time,” she says. “I send him everything.” Benton particularly likes getting photos of Charlotte to see how his hometown is changing. He enjoys seeing his nephew dressed up on Halloween and his mother on Mother’s Day.

Benton has missed more than a decade’s worth of Thanksgiving dinners, birthdays and Christmases, but for Whitten the grief is at its sharpest during unexpected, serendipitous moments. Like when Benton’s 5-year-old nephew came into the living room fresh from a bath in his Darth Vader robe and cuddled up to her dog, who wore a matching Star Wars dressing gown.

Whitten couldn’t stop laughing at the pair. She wished Benton had been there to see them. So, she did what she always does when that familiar pang sets in: she snapped a photo on her phone and uploaded it to Pigeonly. Just like she does most days when she wakes up, to wish him a good morning. “I just want to give him real life because that’s what he’s missing,” she says. “It might sound small, but that’s something we weren’t able to do before.” Benton says the photos are pinned up on the walls of his cell and remind him of home. “It makes me want to get there even faster,” he wrote in an email from prison. “It also makes me think of my freedom and how I gots to get out and stay out.”

A year before Pigeonly was launched, two former convicts hailing from different parts of the U.S. hatched similar ideas.

Scott Levine was convicted of stealing information from a data-management company—which prosecutors at the time called the largest federal computer theft indictment—and spent more than five years in the Miami Federal Correctional Institution. In federal prison, you either pay 21 cents per minute for long distance calls or the six-cent per minute local rate and Levine felt the pain of the complex and costly communication system when trying to keep in touch with his children. Upon release, he launched InmateAid, which lets subscribers sidestep long-distance rates by facilitating an online connection at local phone rates regardless of your geographical location, for a monthly $8.95 fee. This has cut the calling costs for some families down from $750 a month to just $50.

The startup, bankrolled and co-founded by philanthropist Shawn Friedkin, has grown into the largest online database of U.S. correctional institutions, serving some 1.2 million visitors and connecting tens of thousands of customers a month. “When you first go in [to prison], people keep in touch for a month or so and then they start to forget,” Levine says. “They’ll take photos and leave them sitting in the camera instead of printing them out and there’s no way to turn it into something tangible without a lot of effort. We are trying to make it easier for people who are walking around all day with a smartphone in their pocket, not a typewriter or a pen and paper.”

That same year, Marcus Bullock decided to launch an app to help him stay in touch with the friends he grew up with behind bars in a maximum security federal prison in Virginia. Bullock was sentenced to eight years after being caught car-jacking at the age of 15. Every day, his mother would take photos, print them out and post them to him, keeping him involved in her day to day life. “It allowed me to be able to keep my head strong and see the world through her eyes and realize there was still life for me outside of prison,” he says.

Now 37, Bullock runs Washington D.C-based Flikshop, which lets users send a postcard bearing a photo and message into prisons for 99 cents. He initially bootstrapped the business with the help of family and friends, but has since received financial support from celebrity investors like NBA All-Star Baron Davis and pop singer John Legend.

Many prisons welcome the new technology, viewing the start-ups as potential allies in the war against contraband. In September, the Lancaster County Prison in Pennsylvania decided to ban all greeting cards—which were being laced with dangerous synthetic drugs—unless they were posted via Pigeonly. These services are a “win-win for everybody,” says Tammy Moyer, the facility’s director of administrations.

Up until the late 20th Century, the only way to stay in touch with an inmate was to either visit in person, navigate the expensive and complex phone system or write a letter. But because prisoners can be moved to another facility with no warning, it can be hard to keep track of their location, and some families simply can’t afford to visit a loved one jailed in a different state.

In 2009, email arrived at federal facilities via the Trust Fund Limited Inmate Computer System, which is operated by CorrLinks, a subsidiary of Advanced Technologies Group. It’s a basic messaging service that operates outside the internet. Inmates pay five cents a minute for computer time and an extra 15 cents per page to print. State-run prisons have a similar email system called JPay, owned by the prison technology company Securas Technologies Inc. JPay messages cost from 15 cents to 47 cents apiece and are screened for sexual references, drug smuggling and escape schemes. In a modernizing bid, JPay now offers Snap N’ Sends and VideoGrams, which let families and friends send Snapchat-style messages to inmates via email.

While these services made it easier for people on the outside to stay in touch, life on the inside got harder. Short, depersonalized email threads replaced hand-written letters that used to run pages long. The excitement of hearing your name announced at the daily mail call was replaced with long queues for the computer.

“Mail call is like Christmas every day in prison,” says Teresa Hodge, who spent almost six years in the Alderson West Virginia Prison Camp for fraud. “The importance of hearing your name called, of getting something from the outside—it’s a sense of validation that people care, that you still matter. I can’t imagine those 70 months without remaining connected to my family. It allowed me to keep my head strong and realize there was still life for me outside.”

Hodge, who co-founded Mission: Launch Inc., a nonprofit that helps former prisoners reenter the workforce, recalls the difficulty she had staying in touch with her daughter from behind bars. Phone calls were over-priced and to email she had to queue up with 1,100 other inmates to use one of 15 computers, paying five cents a minute. That might not sound like a lot, Hodge says, but it is when you only earn eight cents an hour and don’t want your family picking up the tab. It’s “high-pressured reading and writing because you’re paying for every minute,” she says. “We are in the 21st Century, and prison is definitely in the 19th Century.”

In an ideal world, these apps wouldn’t be necessary because communication into prisons would be free—monitored and limited, but free—says Justice Policy Institute Executive Director Marc Schindler. “This is an area that has room for lots of improvement, including exploitative practices,” he says.

Devron Wadlington, 34, has spent almost half his life behind bars. He was handed a 17-year prison sentence for killing an intruder who shot him during a home invasion when he was only 18. Wadlington is in the Green River Correctional Complex in Kentucky. During a phone interview (which was disconnected four times) Wadlington says he pays 42 cents for every email he sends and 21 cents a minute for each phone call. “It’s all about the dollar bill with this whole correctional system,” Wadlington says. “Everyone is making a profit off us. They capitalize off of our desire to keep in touch with people on the outside.”

Wadlington lives with 200 other inmates and says there is always a line for the two computers located in his housing block. The computers lock you out after 15 minutes to ensure everyone gets a turn, but Wadlington says it’s hard to digest an email and reply in such a short time span—particularly for slow typers.

Technology has changed the way his friends and family stay in contact, Wadlington says. He was incarcerated before email was introduced into prisons and he witnessed the rise and fall of the popularity of the service. He prefers it when family and friends post a letter and says he has both Pigeonly and Flikshop photos pinned up on the walls of his cell.

“I’d rather have pictures in my cell so when I first open my eyes in the morning I see someone I love and I know they love me back; this reminds me that I still have hope outside this place,” Wadlington says. “It’s always good to get your name called out at mail call. Whenever they hand out the mail, I’m hoping they call out my name. Us people in here, we need that.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Robin Ajello at rajello@bloomberg.net, Molly Schuetz

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.