A CEO Council on Climate Change? That Sounds Familiar

A CEO Council on Climate Change? That Sounds Familiar

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Earlier this month, the CEOs of 13 Fortune 500 companies, along with a handful of environmental groups, issued a call to enact federal legislation to fight the impacts of climate change. Their initiative suggests a carbon-pricing policy that would “meet the climate challenge at the lowest possible cost.” This CEO Climate Dialogue — top-down, policy-driven and designed to garner bipartisan support — adds to a wide field of big businesses, financial institutions, and state and local governments advocating limits on greenhouse gas emissions.

If this all sounds like a movie you’ve seen before, that’s because it is.

Twelve years ago, a similar group (featuring some of the same players) formed the U.S. Climate Action Partnership, a large corporate push for legislation to cap carbon dioxide emissions. USCAP was also about big business; it was about carbon pricing; it was about bipartisanship. And it went nowhere.

The cynic in me says that regardless of political or actual climate, any grand plan that includes mentions of “climate,” “carbon,” “price,” “tax,” “limit,” “regulation,” “essential” or “policy” is probably a nonstarter. Grand plans didn’t work before, and they probably won’t work now. But much has changed since 2007, and what’s different makes me less cynical about big-business-led efforts to decarbonize themselves and, by extent, the economy.

To get to my less cynical perspective, we need a bit of history. As Kevin Book of Clearview Energy Partners told me:

The economic basis for the climate story in 2007 is a completely different story to today. Then, saving hydrocarbons and reducing emissions were aligned. We were short hydrocarbons in the world, and the ideas of conserving hydrocarbons and reducing emissions were totally aligned.

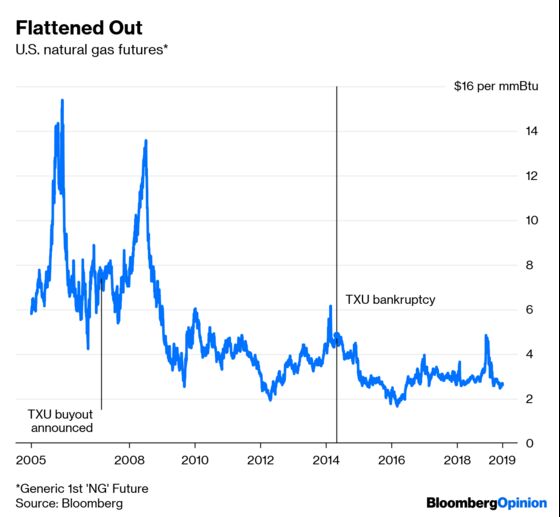

Book is right — oil was expensive and scarce; so was gas. Coal-fired power was still seen as the basis of the U.S. electricity mix as it was cheap and the fuel was domestically sourced. Coal fueled half of all power generation. Emissions were rising as a result. This expectation that coal would remain the cheapest power source was at work during the leveraged buyout of TXU Corp., the largest LBO ever at the time.

One of TXU’s major concessions in the deal was to cut the number of its planned new coal plants to three from 11 — significant enough to earn the endorsement of two large nongovernmental organizations, Environmental Defense and the Natural Resources Defense Council. In announcing the deal, TXU also said it sought “to join the United States Climate Action Partnership.” Fewer coal plants would mean that TXU had fewer lower-cost generators to compete against higher-cost gas-fired plants, but it also meant, in theory, that its existing coal plants would stay competitive in the power market.

At the time, natural gas futures were a little more than a year past a spike beyond $15 per million British thermal units, and a bit less than a year from another run-up to almost $14 per mmBtu.

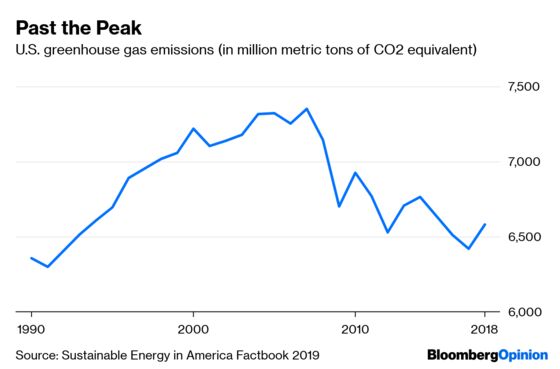

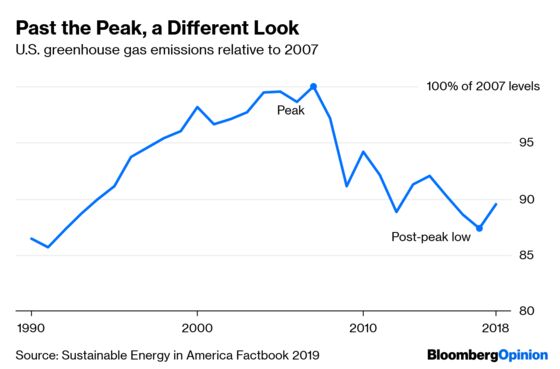

But just as USCAP was being proposed, two things happened: The economy slowed (and then went into recession) and an enormous amount of natural gas supply entered the market. Renewable power generation grew enormously, and the economy became more energy-efficient. U.S. greenhouse gas emissions would, it turns out, reach their peak in 2007.

USCAP’s medium-term greenhouse gas emissions target was 90% to 100% of current levels within 10 years of enactment. Despite the failure of the group’s strategy, that goal was reached anyway. Here are those same data, charted as a percent of 2007 levels:

Here’s what happened to natural gas futures after that 2008 peak: They dropped to half their level when the TXU buyout was announced. TXU, heavily indebted and facing those “relentlessly unfavorable natural gas prices” that made its coal fleet uneconomical, filed for bankruptcy in 2014.

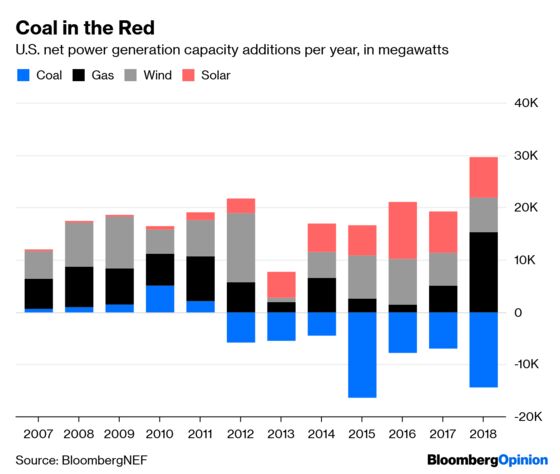

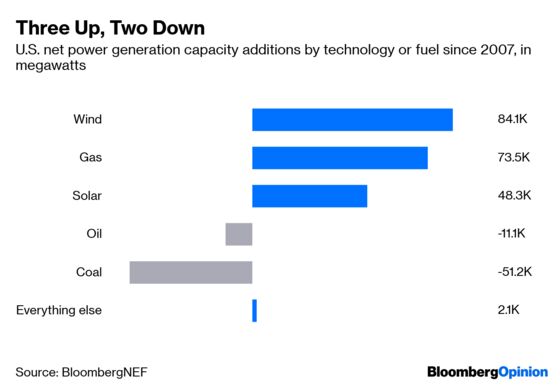

With cheap gas came far more gas-fired power generation in the U.S. Renewables surged, too, while the coal fleet stopped growing in 2011 and has been shrinking ever since. Those changes have been massive contributors to the U.S.’s falling emissions.

Sum up those net additions since 2007 by technology or fuel, and the change looks pretty stark. Wind, solar and gas make up the vast bulk of all growth — at the expense of coal and oil.

The future fortunes of coal in power generation is something I write about often, mostly because coal has been the backbone of so many electricity systems for so long. That status made any concession around coal a big deal in 2007. Coal is mentioned 22 times in USCAP’s 2009 “A Blueprint for Legislative Action”; it isn’t mentioned once in any of the CEO Climate Dialogue’s documents.

Even BHP Group’s chief financial officer, Peter Beaven, said at the mining giant’s recent annual general meeting that coal used for power generation is being “phased out, potentially sooner than expected.” That statement is even more interesting when you note that BHP is bullish on materials used in renewable energy and electric vehicles.

A lot has changed in the 12 years since USCAP was announced. Hydrocarbons are cheap and abundant, but renewable energy is even cheaper in many places, and getting cheaper still. Scarcity isn’t an issue. But climate change looms far larger than it did in 2007. As Book told me:

Today, the societal focus isn’t on the climate itself, but climate bolted onto a much more potent substrate: the Green New Deal. The Green New Deal doesn’t exist except as a mobilization and a movement, but it appeals societally on a human rather than a geologic time scale: 10 years.

I don’t think today’s politics will allow for a top-down, centralized, price-based measure to limit carbon emissions. It was hard 12 years ago; it’s hard now. It’s still important to look back and appreciate all that has changed in energy supply, demand and technology. It’s probably more important as we look ahead via thoughtful explorations of what a massive mobilization to decarbonize might look like. Put the pieces of the history and the future together, and maybe we have hope that it’ll be different this time around.

Weekend reading

- “Owned by passionate idiots” is a much worse thing to short than something “owned by people who are leveraged and will face margin calls.”

- Germany has approved a $45 billion aid package for the nation’s coal-producing regions.

- The president of the Niskanen Center says he changed his mind about climate change because he changed his mind about risk management.

- Scientists have brewed beer using the yeast colonies found in Egyptian pottery shards. The Pharaonic beer “isn’t bad,” apparently.

- In 1962, a 20-pound chunk of the Soviet satellite Sputnik 4 landed in the middle of a street in Wisconsin, still hot.

- Starting in July, Transport for London will track every Wi-Fi-enabled device on the London Underground. Want to opt out? Turn off your Wi-Fi.

- New York City’s subway is unveiling tap-to-pay capabilities, 20 years after switching from tokens to MetroCards and 22 years after Hong Kong launched its contactless Octopus card.

- A United Nations study titled “I’d Blush If I Could” finds that female voice assistants reinforce gender stereotypes.

- Google Glass has launched the second iteration of its Enterprise Edition wearable computer, and it’s compatible with safety frames.

- Does Google’s CEO have the right to be forgotten?

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brooke Sample at bsample1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nathaniel Bullard is a BloombergNEF energy analyst, covering technology and business model innovation and system-wide resource transitions.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.