Big Batteries Are All the Rage, But This One’s 16 Years Old

Big Batteries Are All the Rage, But This One’s 16 Years Old

(Bloomberg) -- New York City dove headlong into the race to build bigger and bigger batteries this week, as regulators approved plans for a massive system on the East River in Queens.

But for those keeping score, the biggest of all in America has been quietly at work for almost 16 years in a far more remote corner of America: a warehouse in central Alaska.

The 46-megawatt battery, in Fairbanks, uses a chemistry that’s largely gone the way of fax machines. It’s old enough that its operators can’t find replacement parts for some components. But it still works, keeping the lights on in the city of 32,000 near the Arctic Circle, preventing 59 blackouts last year alone.

“Our system operators are very adamant that they don’t want it to go away,” said Dan Bishop, manager of engineering services for the Golden Valley Electric Association, which owns the battery.

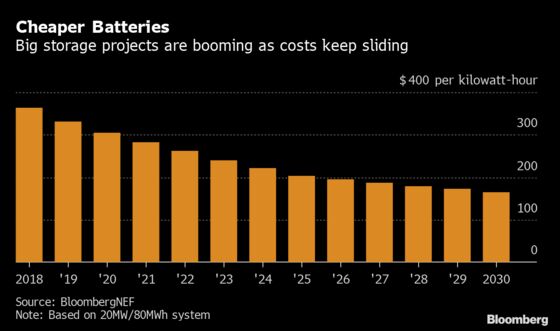

The push to install bigger and bigger batteries on U.S. electric grids comes as the price of lithium-ion systems has plummeted and states try to squeeze out fossil fuels. By soaking up excess power and dispatching it when demand spikes, batteries can help keep grids stable and smoothly incorporate ebbs and flows of wind and solar. They can also displace so called peaker natural-gas plants that kick in only when demand surges.

So far, battery systems capable of storing about 5.5 gigawatts of electricity have been installed worldwide, with more than 6 gigawatts under development, according to BloombergNEF data. A gigawatt is roughly the output of one commercial nuclear reactor.

Dubbed the BESS, for Battery Energy Storage System, the array in Alaska uses 13,760 nickel-cadmium cells, stacked in rows. Guinness World Records certified it as the world’s most powerful battery when it was commissioned in 2003. It’s since lost its global crown as systems including Tesla Inc.’s 100-megawatt battery in Australia have come online.

Now several installations planned in the U.S. are poised to eclipse it, too.

In California, Tesla is building a 182.5-megawatt installation for PG&E Corp. In Florida, NextEra Energy Inc.’s Florida Power & Light utility is planning a 409-megawatt battery pack. Meanwhile, New York’s battery at the Ravenswood power plant in Long Island City will be built in three phases, with the first coming online in 2021.

An ‘Islanded’ Grid

But for now, the BESS remains king.

For the record, the U.S. Energy Department considers BESS to be tied with a battery in California as the country’s largest, listing the capacity of both at 40 megawatts. Golden Valley, however, says its system in Alaska weighs in at 46 megawatts.

Designed by ABB Ltd. with cells from Saft Groupe SA, the $35 million system kicks in whenever there’s an interruption in electricity supply. The Alaskan interior lacks the densely woven web of power lines found in much of the country, and blackouts used to be common, said Tom DeLong, chairman of Golden Valley’s board of directors.

“We were islanded -- we had basically one big extension cord down to Anchorage,” he said. “Everyone in Fairbanks, when I was here in the 70s and 80s, had a generator in their garage.”

As such, the BESS represents an earlier generation of energy-storage projects, BloombergNEF analyst Logan Goldie-Scot said. The large-scale batteries now being installed provide a variety of services: helping maintain grid stability, storing excess electricity from wind and solar and in some cases replacing small power plants. But in BESS’s day, large batteries often served relatively remote communities that needed a backup power source in a pinch, Goldie-Scot said.

Like any aging system, BESS needs work. Half its cells have been replaced, and the control system now needs an upgrade or replacement. Golden Valley, however, has no plans to ditch it.

“Not unlike your other computer-based things, after a certain amount of time, the chips aren’t made anymore,” Bishop said.

--With assistance from Will Wade.

To contact the reporter on this story: David R. Baker in San Francisco at dbaker116@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Lynn Doan at ldoan6@bloomberg.net, Joe Ryan, Will Wade

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.