A Blood Test Can Predict Dementia. Trouble Is, There's No Cure

In the absence of medical breakthroughs, the worldwide cost of dementia is projected double to $2 trillion by 2030.

(Bloomberg) -- Nobel prizewinner Koichi Tanaka says the predictive blood test for Alzheimer’s disease he and colleagues spent almost a decade developing is a double-edged sword.

Without medications to stave off the memory-robbing condition, identifying those at risk will do nothing to ease the dementia burden and may fuel anxiety. But used to identify the best patients to enroll in drug studies, the minimally invasive exam could speed the development of therapies for the 152 million people predicted to develop the illness by 2050.

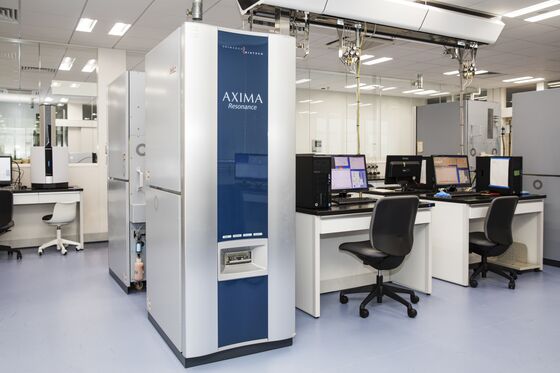

“We must be cautious on how the test is used because there’s no curative treatment,” Tanaka said in an interview at Kyoto, Japan-based Shimadzu Corp., where he’s worked for 36 years. The 59-year-old engineer, who shared the Nobel for chemistry in 2002, said he hopes the test he helped pioneer will one day be administered routinely, but right now it belongs in the hands of drug developers and research laboratories.

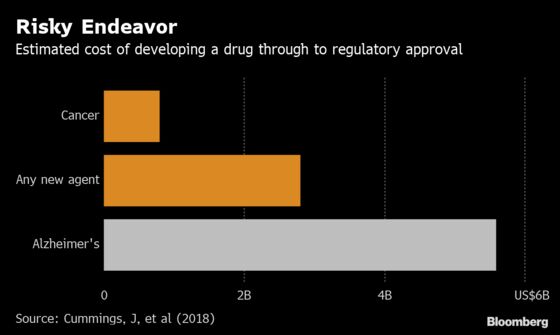

More than a century after the telltale signs of Alzheimer’s were first seen under a microscope, and billions of dollars in research spending by Roche Holding AG, Eli Lilly & Co., Eisai Co. and other companies, there’s still no drug slow down the disease.

In the absence of medical breakthroughs, the worldwide cost of dementia is projected double to $2 trillion by 2030.

While scientists debate the cause of Alzheimer’s, most agree that no treatment is likely to work on patients with significant cognitive impairment. That’s because their brains have been irreversibly damaged by clumps of misfolded and abnormal proteins that jam nerve cells.

Nature Study

“There are many reasons why drugmakers have failed to develop a cure for Alzheimer’s disease, but it’s too late to start treatment when patients already show symptoms,” Tanaka said.

In a study published in Nature in January last year, Tanaka and colleagues showed it was possible to use a novel biomarker discovered by his lab to accurately quantify minute traces of amyloid-beta from a teaspoonful of blood, and gauge the progression of Alzheimer’s -- allowing identification of people likely to develop dementia over the coming decades.

Previously, the brain changes that occur long before Alzheimer’s symptoms appear could only be reliably assessed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron-emission tomography (PET) scans, and from measuring amyloid and another errant protein called tau in spinal cord fluid -- methods that are expensive and, in the case of a spinal tap, invasive.

“Our finding overturned the common belief that it wouldn’t be possible to estimate amyloid accumulation in the brain from blood,” Tanaka said. “We’re now being chased by others, and the competition is intensifying.”

Roche, Quanterix

About a dozen companies and research groups from around the world, including Roche, Spain’s Araclon Biotech SL, and Lexington, Massachusetts-based Quanterix Corp., are pursuing blood-based diagnostic tools for Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases.

“These blood tests are very important to that aim of trying to get these groups identified and ready to go into trials, and make them faster and less expensive,” said Christopher Rowe, a neurologist who heads molecular imaging research at the Austin Hospital in Melbourne. “That, in turn, is the greatest hope for having a significant impact on the epidemic.”

The global Alzheimer’s disease diagnostics and therapeutics market is predicted to reach $11.1 billion in 2024 from $7.5 billion last year, ResearchAndMarkets.com said in March.

The greatest benefit from screening blood tests for Alzheimer’s will come once treatments are available to prevent dementia symptoms, said Randall Bateman, the Charles F. and Joanne Knight distinguished professor of neurology at Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis. Bateman and colleagues presented in 2017 a new method for measuring plasma amyloid levels using a similar approach to Tanaka’s group.

‘Exceptional Accuracy’

“You really get exceptional accuracy,” said Bateman, whose lab studies the causes, diagnosis and treatments of Alzheimer’s disease. “I could see that easily becoming a clinical standard.”

Both the Shimadzu and Washington University groups use an analytical technique called mass spectrometry that can search for a particular compound based on its specific molecular weight and charge. The method was found to be 90% accurate when it was checked against brain scans, Tanaka and colleagues said in their Nature paper.

Tanaka likens the approach to fishing with bait that only a specific fish will take. It enabled him to more precisely quantify amyloid in blood than an older, antibody-based method, he said.

New digital technology has bolstered the antibody-based test, with Quanterix using it to detect the errant proteins associated with the start of Alzheimer’s disease, as well as neurofilament light chain -- a marker of neurological injury that can be elevated by conditions including concussion, Parkinson’s and multiple sclerosis.

“There’s an incredible opportunity to transform brain health by understanding your neuro baseline,” said Kevin Hrusovsky, Quanterix’s chief executive officer.

‘Game-Changing’

Several drugmakers are trying to get tests for neurofilament light chain validated clinically as a complementary diagnostic tool because they will enable patients’ responses to medications to be monitored in real time, providing an early signal of efficacy, Hrusovsky said. “There’s a lot of evidence that this is going to be game-changing,” he said.

Roche is evaluating the use of Elecsys, which tests cerebrospinal fluid for signs of Alzheimer’s, in blood plasma, the Swiss company said in an emailed response to questions.

The global demand for tests that can provide an early and accurate Alzheimer’s diagnosis, as well as predict the disease trajectory is “enormous, with 50 million people already affected today and many more people going undiagnosed,” according to Roche. “It’s a market that has room for many different technologies and players, from digital biomarkers to imaging and protein biomarkers.”

Shimadzu finished analyzing amyloid levels in blood-serum samples from 2,000 patients in March, Tanaka said. The company is preparing to offer the service in the U.S. this year before extending it to Europe and China.

“One thing we are looking into is running prospective cohort studies targeting people who have started to build up amyloid in the brain and see whether anything -- food, exercise -- can intervene to slow the progression of the disease,” the Nobel laureate said. “There are many things to be done.”

--With assistance from Jason Gale and Tim Loh.

To contact the reporter on this story: Kanoko Matsuyama in Tokyo at kmatsuyama2@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Rachel Chang at wchang98@bloomberg.net, ;Adam Majendie at adammajendie@bloomberg.net, Jason Gale, John Lauerman

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.