I Took DNA Tests in the U.S. and China. The Results Concern Me

Privacy is big concern, as governments seek access to DNA data.

(Bloomberg) -- Spitting into the plastic test tube, I felt nervous. I was offering up a piece of myself for decoding, and while this time there was no silver-haired sage, it reminded me of a visit to a fortune teller when I was 21.

Then, I offered the palm of my hand in a bid to divine what fate had planned for me. Now, it was DNA, with my saliva destined for a laboratory in southwest China, to the headquarters of Chengdu 23Mofang Biotechnology Co., a startup that’s seeking to tap a boom in consumer genetics in the world’s most populous nation.

Rising awareness of genetically-linked diseases like Alzheimer’s and a natural human curiosity for insight into the future is fueling a global market for direct-to-consumer DNA testing that’s predicted to triple over the next six years. In China, where the government has embraced genetics as part of its push to become a scientific superpower, the industry is expected to see $405 million in sales by 2022, according to Beijing research firm EO Intelligence, an eight-fold increase from 2018. Some 4 million people will send away test tubes of spit in China this year, and I had just become one of them.

Not only was I entering a world where lack of regulation has spawned an entire industry devoted to identifying the future talents of newborn babies through their genes, I was handing over my genetic code to a country where the government has been accused of using DNA testing to profile minority groups — a concern that hit home when the results showed I was a member of one.

I wanted to see whether the burgeoning industry delivered on its claims in China, where scientists have gained international attention — and criticism — for pushing the boundaries of genetics. And as a child of Vietnamese immigrants to the U.S., I’ve long been curious about my ancestry and genetic makeup.

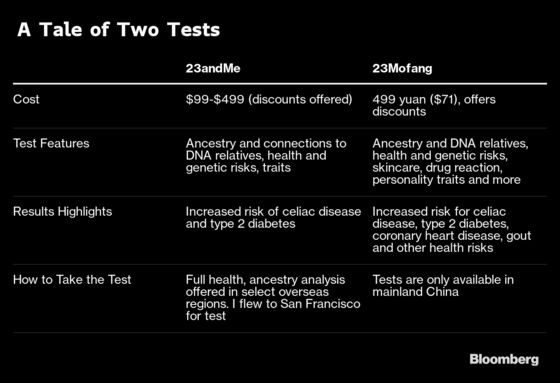

To get an idea of how this phenomenon is playing out in the world’s two biggest consumer markets, I compared the DNA testing experience of 23Mofang with the firm CEO Zhou Kun says it was “inspired” by: 23andMe Inc., one of the best known consumer genetics outfits in the U.S.

The differences between the two companies are stark.

23andMe was co-founded by Anne Wojcicki, a Wall Street biotech analyst once married to Google co-founder Sergey Brin. The Mountain View, California-based firm has more than 10 million customers and has collected 1 billion genetic data points, according to its website. Brin and Google were early investors.

By contrast, 23Mofang is run out of the Chinese city of Chengdu, and Zhou, 36, is a computer science graduate who created the company after becoming convinced China’s next boom would be in the life sciences sector. 23Mofang expects to have 700,000 customers by the end of this year, a number he projects will at least double in 2020.

The divergence between the two countries and their regulation of the industry is just as palpable. China’s race to dominate genetics has seen it push ethical envelopes, with scientist He Jiankui sparking a global outcry last year by claiming to have edited the genes of twin baby girls. The experiment, which He said made them immune to HIV, put a spotlight on China’s laissez-faire approach to regulating genetic science and the businesses that have sprung up around it.

When my reports came back, 23Mofang’s analysis was much more ambitious than its American peer. Its results gauged how long I will live, diagnosed a high propensity for saggy skin (recommending I use products including Olay and Estee Lauder creams) and gave me — an optimist not prone to mood swings — a higher-than-average risk of developing bipolar disorder. 23andMe doesn’t assess mental illness, which Gil McVean, a geneticist at Oxford University, says is highly influenced by both environmental and genetic factors.

The fortune teller who pored over my palm told me I would live to be a very old woman. 23Mofang initially said I had a better-than-average chance of living to 95, before revising the results to say 58% of clients had the same results as I did, making me not that special, and perhaps not that long-living.

When I ran the finding past Eric Topol, a geneticist who founded the Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla, California, he laughed. “Ninety-five years old? There’s no way to put a number on longevity,” he said. “It’s a gimmick. It’s so ridiculous.”

Zhou said the accuracy of the longevity analysis, based on a 2014 genetics paper, is “not too bad,” though the company plans to update the analysis with research that’s being undertaken on Chinese elderly.

But when it comes to disease, the results of both companies showed how the science of genetics, particularly at the consumer level, is still a moving target.

After claiming I had a 48% greater risk than the general population of developing type 2 diabetes, both 23Mofang and 23andMe then revised the results.

First, 23andMe cut the risk figure from its analysis, posted in an online portal I accessed with a password. The overview analysis that I have an increased likelihood of developing the disease never changed. But a few months later, the figure was back, with a slightly different explanation: “Based on data from 23andMe research participants, people of European descent with genetics like yours have an estimated 48% chance of developing type 2 diabetes at some point between your current age and 80.”

Shirley Wu, 23andMe’s director of health product, said the company occasionally updates its analysis of various reports. The company hasn't updated its type 2 diabetes report since it was launched in March. If I had updated my ethnicity, age or sex on my profile, that may have led to changes in risk percentages, the company said. I had not.

“Your risk estimates will likely change over time as science gets better and as we have more data,” said Wu, referring to test reports in general. “We are layering in different non-genetic risk factors, and that potentially updates our estimates.”

Algorithms and data underpin the analysis of both companies, as they do for other genetic testing firms, so it apparently isn’t unusual for DNA analysis to shift as more research and data into diseases become available. Still, I was confused.

I reached out to Topol, who said that 23andMe’s diabetes finding likely didn’t apply to me since the vast majority of people studied for the disease are of European descent. Wu said the American company does have a “predominantly European database” but has increased efforts to gather data for other ethnicities as well.

23Mofang, meanwhile, also revised my diabetes risk — to 26%. My genes hadn’t changed, so why had the results? CEO Zhou said the company is constantly updating its research and datasets, and that may change the analysis. As time goes by, there will be fewer corrections and greater accuracy, he said.

For now, “there’s a possibility you can later get a result that’s opposite of the initial analysis,” said Zhou.

Additionally, the accuracy of genetic analysis “varies hugely” depending on the traits and conditions tested because some are less genetically linked than others.

Zhou isn’t deterred by criticism. He said 23Mofang employs big data and artificial intelligence to find the correlations to diseases “without relying on scientists to figure it out.”

While it’s impossible to get things “100% right,” the company’s accuracy will get better with more data, he said.

You might assume that the two companies would offer similar analysis of my ancestry, which I’ve long thought to be three-fourths Vietnamese and one-fourth Chinese (my paternal grandfather migrated from China as a young man). Born in Vietnam and raised in the U.S., I now live in Hong Kong, a special administrative region of China.

23andMe’s analysis mirrored what I knew, but my ancestry according to 23Mofang? 63% Han Chinese, 22% Dai — an ethnic group in southwestern China — and 3% Uighur. (It didn’t pick up my Vietnam ancestry because the analysis only compares my genetics to those of other Chinese, according to the company.)

That led me to the big question in this grand experiment: How safe is my data after these tests?

Human Rights Watch said in 2017 that Chinese authorities collected DNA samples from millions of people in Xinjiang, the predominately Muslim region that’s home to the Uighur ethnic group. China’s use of mass detention and surveillance in the region has drawn international condemnation. What if Beijing compelled companies to relinquish data on all clients with Uighur ancestry? Could the details of my Uighur heritage fall into government hands and put me at risk of discrimination or extra scrutiny on visits to China?

23Mofang’s response to these questions didn’t give me much solace. Regulations enacted in July gave the government access to data held by genetics companies for national security, public health and social interest reasons. The company “respects the law,” said Zhou. “If the law permits the government‘s access to the data, we will give it,” he said.

The authorities haven’t made any requests for customer data yet, Zhou pointed out. China’s State Council, which issued the regulations, and the Ministry of Science & Technology didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Over in the U.S., 23andMe said it never shares customer data with law enforcement unless there’s a legally valid request such as a search warrant or written court order. The company said it’s had seven government requests for data on 10 individual accounts since 2015 and has not turned over any individual customer data. It uses all legal measures to challenge such requests to protect customers’ privacy, said spokeswoman Christine Pai.

New York University bioethics professor Art Caplan says privacy protections on genetic information are poor in most countries, including in the U.S. and China.

“I don’t think anyone can say they’re going to protect you,” he said. “In China, it’s even easier for the government. The government retains the right to look.”

23andMe appeals to potential customers with the lure of being able to “make more informed decisions about your health,” but after taking tests on both sides of the Pacific and realizing how malleable the data can be, as well as the myriad factors that determine diseases and conditions, I am left more skeptical than enlightened.

I gave away something more valuable than a vial of spit — the keys to my identity. It could become a powerful tool in understanding disease and developing new medicines, but in the end it’s entrepreneurs like Zhou who will ultimately decide what to do with my genetic data. He plans to eventually look for commercial uses, like working with pharmaceutical companies to develop medicines for specific diseases.

“We want to leverage the big database we are putting together on Chinese people,” Zhou said. “But first, we need to figure out how to do it ethically.”

--With assistance from Jinshan Hong, April Ma and Lulu Chen.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Anjali Cordeiro at acordeiro2@bloomberg.net, Emma O'BrienJohn Lauerman

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.