Suicides, Traffic Hell in NYC Spur Second Look at Uber's Growth

In New York, the rise of Uber and other ride-share companies means gridlock on Manhattan streets.

(Bloomberg) -- In New York, the rise of Uber and other ride-share companies means gridlock on Manhattan streets, as more cabs than ever vie to serve commuters, residents and tourists. It also means a decimated taxi industry, punctuated by the suicides of six cabbies in seven months.

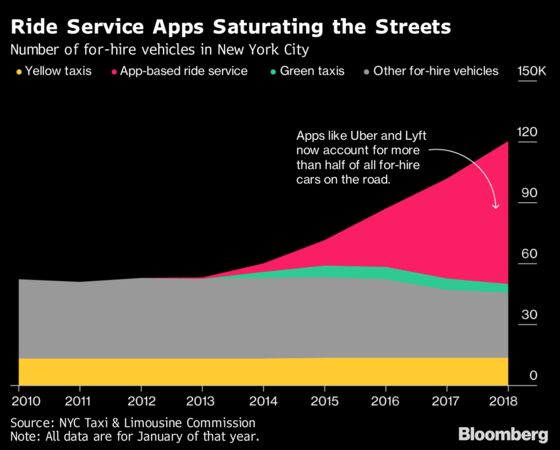

Three years ago, Mayor Bill de Blasio sought a temporary cap on Uber’s growth to study its impact on congestion. The City Council did away with that proposal after the company ran a million-dollar television ad and lobbying campaign. At the time, 12,600 app-based transportation vehicles navigated city streets. Today there’s 80,000, with 2,000 added every month.

De Blasio, a second-term Democrat, says the Council is now responsible for solving two major problems caused by this exponential increase: drivers unable to make a living, and the economic toll that clogged roads take on city businesses. The Council is studying new regulations to address both issues, but there’s no timetable for action.

“While I’m open to some sort of cap, I’m concerned it may be too late with so many Uber drivers already on the streets,” Council Speaker Corey Johnson, who helped quash the attempted Uber limit in 2015, said in an interview. “I have concerns about whether it would accomplish everything we want.”

The debate mirrors an international discussion over how to regulate ride-sharing services like Uber Technologies Inc., which launched in its home base of San Francisco in 2009 and came to New York in 2011. It’s now in more than 300 cities in 56 countries.

In London, Uber continues to operate while awaiting a court hearing this month to renew its license, which regulators revoked amid safety concerns. Denmark has insisted its cars have fare meters. Regulatory disputes have prompted suspensions in Finland, France, Spain, Hungary and the Netherlands. Last December, the European Court of Justice, the EU’s highest tribunal, rejected the company’s contention that it was merely a web app, ruling it could be regulated the same as any other taxi service.

American Dream

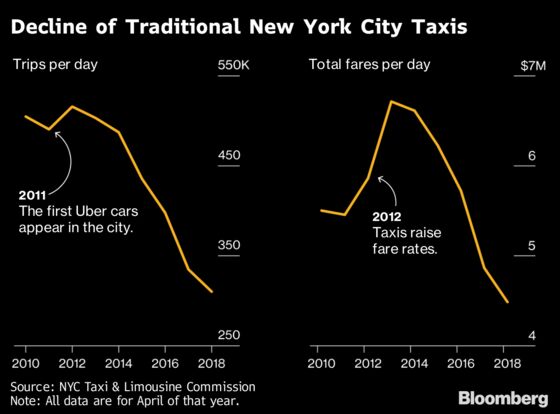

In New York, Uber’s rise is killing the traditional yellow taxi industry. Cab driving used to provide immigrants a possible pathway to a better life, said Bhairavi Desai, a spokeswoman for the Taxi Workers Alliance, an organization representing hundreds of drivers.

“It’s become a real race to the bottom, a financial crisis borne of political failure, and we need political action to fix it,” Desai said. “There are real human consequences to a business model predicated on destroying labor standards and treating workers as expendable.”

Jason Post, an Uber spokesman, said the company provides jobs for tens of thousands of New Yorkers and transportation choices for residents. “New vehicles keep up with the growing demand for rides outside of Manhattan,” he said.

A cap “would only hurt millions of outer-borough riders long ignored by yellow taxis and who don’t have access to reliable public transit,” Post said.

The desperation is particularly felt among drivers who must pay off loans used to purchase one of the city’s 13,500 medallions required to operate a cab. There’s no such cap on how many Uber and Lyft cars may cruise city streets.

The medallion system arose in 1937 to limit the number of taxis that were clogging midtown traffic. Ten years ago, they cost as much as $1 million. Now, some owners say they can’t find a buyer.

For the past six months, Desai has been appearing at rallies and memorial services for drivers who have taken their lives.

Alfredo Perez hanged himself in November from a fence post in the Bronx; Nicanor Ochisor in March from a wood beam in a Queens garage. Danilo Castillo jumped off a roof in northern Manhattan in December, hours after a hearing about a possible license revocation.

In February, Douglas Schifter shot himself in his car in front of City Hall, blaming politicians for not stopping Uber’s growth. Last month, Kenny Chow jumped into the East River and drowned two blocks from the mayor’s residence. And just Friday, Abdul Saleh hung himself in his Brooklyn apartment after struggling financially for months, according to Desai and local news reports.

“We are being destroyed by our Government individually as well as an industry,” Schifter wrote in a Facebook post hours before he took his life. “When will they realize what they are doing to us? What does it take to bring us the attention we need?”

City Gridlock

The Uber issues must be addressed as part of the broader transportation crisis in the most populous U.S. city, said Matthew Daus, a New York-based national transportation consultant who led the city Taxi & Limousine Commission for more than eight years. New York’s century-old subway system is beset by delays and breakdowns. The rail tunnel that connects New Jersey workers to New York City jobs is over-capacity and falling apart.

Daus suggests a “holistic approach” taking into account the city’s entire surface transportation system, such as those underway in Los Angeles, Seattle, Miami, Denver, Vienna, Singapore and Barcelona. Several of the cities have employed technology developed by MaaS (Mobility as a Service) Global of Helsinki, Finland, whose Whim mobile app assesses all of a city’s transit choices -- whether it’s bus, subway, taxi, Uber, bike or car share -- to help travelers find the best option.

“It’s a quagmire but something needs to be done,” Daus said. “In a perfect world there would be just one system of taxi cabs, but that’s not how history played out.”

Empty Cars

The problem isn’t just too many total cabs; it’s so many circling Manhattan’s central business district looking for fares, de Blasio said. About a third remain empty on average weekdays in Manhattan’s midtown, where traffic creeps at less than 7 miles per hour, 23 percent slower than in 2010, according to an analysis of Taxi & Limousine Commission data by Bruce Schaller, a former deputy commissioner of the city Transportation Department.

That congestion costs the economy about $34 billion a year, according to a report by Inrix Inc., a Kirkland, Washington, transportation consulting group.

“Companies like Uber, they’re constantly trying to increase the number of drivers even when there isn’t an increase in business to go with it,” de Blasio said at a June 5 news conference. “We have more and more drivers going around without a customer, and a lot of the drivers are not doing so well economically on top of that.”

While a temporary cap may be necessary, the long-term solution lies in creating incentives and penalties that encourage for-hire cars to serve neighborhoods outside Manhattan, said Schaller, who has advised the Council staff preparing the new industry regulations.

The city could limit drivers’ time in midtown and impose surcharges or fines when they overstay. Enforcement would be enabled through GPS and other car-monitoring data, he said.

Industry opposition to such rules -- and competing interests among various cab companies -- makes it harder for the Council to address the problem, Schaller said.

“There are policy solutions,” he said. “Whether they get adopted, the proof will be in the pudding.”

--With assistance from Chloe Whiteaker.

To contact the reporter on this story: Henry Goldman in New York at hgoldman@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Flynn McRoberts at fmcroberts1@bloomberg.net, Stacie Sherman

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.