Your Guide to the World Cup’s Corruption Scandals

The politics of hosting the FIFA World Cup.

(Bloomberg) -- No sporting event is more popular than the World Cup. Almost half of humanity — more than 3.2 billion people – tuned in to the month-long competition in Brazil in 2014. But long before nations compete on the field, they vie for the prestige of hosting the tournament that generates billions of dollars in television and sponsorship rights for FIFA, soccer’s ruling body. That competition can spell trouble. Graft scandals have dogged previous tournaments as well as this year's event in Russia and especially the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, raising the question: Is corruption indelibly staining the beautiful game?

The Situation

On the eve of the World Cup in Russia, the U.S., Canada and Mexico were chosen to host the 2026 World Cup, beating Morocco in a vote by member nations of the Fédération Internationale de Football Association. The spate of bribery scandals had prompted FIFA to use a new selection process that wrested the decision from the two-dozen executives who had voted in secret for previous tournaments. That's part of the fallout from a challenging few years for the soccer ruling body: Its long-time president, Sepp Blatter, was banned from the sport for six years, six of its top officials pleaded guilty or were convicted of corruption-related charges in the U.S., and its vice president was arrested by Spanish police investigating graft claims. Although Russia and Qatar's bids were exonerated by a FIFA probe, federal investigations continue in the U.S., Switzerland and France. Blatter's successor, Gianni Infantino, has pledged to restore FIFA's reputation, but the ruling body may be feeling the pinch: Its legal bills are mounting and in the two years after the scandal broke, it failed to attract new major sponsors from Europe or the U.S. FIFA stands to boost revenue by expanding the World Cup to 48 teams from 32 in 2026.

The Background

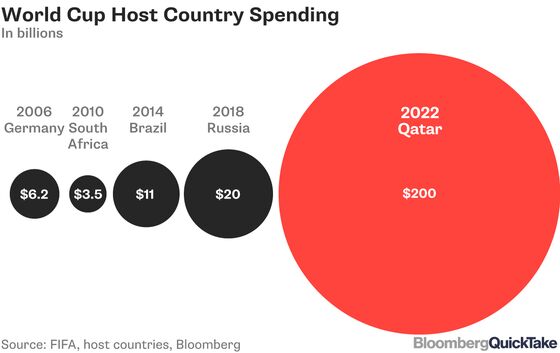

The corruption scandal erupted in 2015 when dozens of soccer executives were arrested in Swiss police raids on a luxury Zurich hotel and the U.S. Justice Department filed multiple charges relating to bribery allegations involving hundreds of millions of dollars. The U.S. probe has led to more than two dozen convictions, including that of the deceased American, Chuck Blazer, the FIFA executive committee member whose whistle-blowing revelations spurred the inquiry. Blazer alleged that he and other committee members accepted bribes in connection with the selection of South Africa as World Cup host in 2010. Disputes over where to hold the event have afflicted the World Cup since it began in 1930. Then, the selection of Uruguay resulted in only four European teams taking part. Uruguay and Argentina boycotted the 1938 competition because Europe was hosting it for the second straight time. FIFA experimented with a rotation system; now, it will take bids only from those continents that haven’t staged either of the last two tournaments. Recent history shows there is little — if any — financial benefit to holding the World Cup. South Africa recouped just a 10th of its outlay on stadiums and infrastructure. Six of the 12 stadiums built for the 2014 Brazil World Cup are now the subject of graft investigations.

The Argument

Blatter said FIFA deliberately pushed the tournament into “new lands” to spread soccer’s popularity and give countries a chance to showcase their culture. Critics highlight the money-losing proposition for developing nations that spend billions of dollars on facilities which might be better invested in other ways. Others say the selection process was made a farce by a voting system that bred foul play, from horse-trading votes to straight up paying for them. While FIFA says it wants to root out its problems and has made changes to its corporate governance, as well as the World Cup selection process, critics say the moves haven’t gone far enough and the ruling body remains resistant to scrutiny and transparency. They question whether appropriate reforms can be carried out by officials long part of the system and argue that FIFA’s one country-one vote system may open the door to skullduggery by giving disproportionate sway to smaller nations. Detractors note that it took pressure from the big corporate sponsors, which each pay about $1.6 billion per World Cup, rather than from FIFA itself to push for Blatter’s removal and press for World Cup bids to be investigated. Even so, FIFA's image may be improving: A 2017 global poll of 25,000 soccer fans found more than half had no confidence in the organization, but a 2018 poll showed that 60 percent of the 12,000 fans surveyed were positive about the ruling body.

The Reference Shelf

- An Amnesty International report about workers’ rights in Qatar and a Human Rights Watch report on the exploitation of foreign workers building's Russia's stadiums.

- Washington Post: How a curmudgeonly old reporter exposed the FIFA scandal that toppled Sepp Blatter.

- Guardian article on the American FIFA executive who took bribes before turning whistle-blower.

- FIFA's new process for selecting a World Cup host.

- Bloomberg Businessweek chronicled Sepp Blatter’s dominance of international soccer in April 2015.

- The BBC detailed FIFA’s corruption woes.

- Full text of the U.S. government’s indictment against nine FIFA officials and five corporate executives. Full text of a second U.S. indictment against 16 other FIFA officials and guilty pleas from two former FIFA executives.

- “Brazil’s Dance With the Devil,” a 2014 book by Dave Zirin.

- A report on the impact of the 2006 World Cup in Germany, and South Africa’s report about the 2010 tournament. A study by the accounting firm KPMG that includes an analysis of the 2010 event in South Africa and a Bloomberg News article about its legacy for Johannesburg commuters.

- John Oliver, host of “Last Week Tonight” on HBO, ranted about FIFA in a June 2014 broadcast.

- A 2016 report by law firm Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, in German, on the award of the 2006 World Cup to Germany. FIFA began an investigation into six individuals following the report.

Tariq Panja and Eben Novy-Williams contributed to the original version of this article.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Grant Clark at gclark@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.