Why Virus Woes Have Put Bond ETFs Under a Microscope

Why Virus Woes Have Put Bond ETFs Under a Microscope

(Bloomberg) -- Two months ago, worries abounded for exchange-traded funds. Invented for small investors and resembling index funds, ETFs provide a low-fee, tax-efficient way for small investors to reduce risk by diversifying portfolios. They’re also generally more liquid -- easier to buy or sell quickly -- than mutual funds or index funds. As the sector boomed to as much as $4.6 trillion in the U.S., some fretted that the ETF’s structure would mean that might not be a crunch. The crunch caused by the pandemic amplified those fears -- until the U.S. Federal Reserve stepped in.

1. What’s an ETF and why do people like them?

Mutual funds allow small investors to pool their money and benefit from the expertise of professional money managers. Index funds and traditional ETFs take a different approach. Instead of hiring managers to actively buy and sell stocks, they seek to replicate the performance of a basket of securities (although a small sliver of the ETF market is actively managed). That allows investors who want some emerging-market or small-cap stocks in their portfolio to avoid the cost, hassle or risk of picking individual companies.

2. How are ETFs and index funds different?

Index funds try to replicate the performance of a benchmark like the S&P 500 by buying all the stocks that comprise the index. In an ETF, investors are buying a share in a bundle of the same securities, and that ETF share can be bought and sold much like a share of stock. The ETFs themselves engage in less trading of assets, because the underlying securities don’t have to be bought or sold when a share changes hands. That smaller turnover means a lower tax bill.

3. How big a part of the market are they?

ETFs currently have $4 trillion in assets, down from their peak of about $4.6 trillion in February, as investors have pared back holdings in the flight to cash over fears of the economic damage caused by the coronavirus pandemic. Equity funds hold about $2.49 trillion, while those focused on bonds contain $770 billion. The most popular ETFs are the simplest, those that track the broad stock market. But these days ETFs come in thousands of flavors and are popular with hedge funds and institutional investors as well as moms and pops. An increasing number track less-traded markets such as junk debt, use derivatives or heavy borrowing to enhance returns, or laser-in on niche segments of the investable universe. That has made regulators consider whether the more exotic versions need to be reined in lest they damage investors and markets alike.

4. What have they been worried about?

Critics and regulators have long voiced concerns that fixed-income ETFs, whose shares are much more liquid than the assets the funds hold, may exacerbate a sell-off as investors scramble to redeem their holdings during periods of market stress.The likes of Mohamed El-Erian of Allianz SE and Scott Minerd at Guggenheim Partners have suggested they could act as a potential destabilizing force in illiquid credit markets where they have an outsized trading share. After finding that fixed-income ETFs fueled volatile trading during August 2015’s stock-market rout, regulators have long planned to closely watch the funds’ activity and performance during the next downturn. That time arrived in March.

5. What happened?

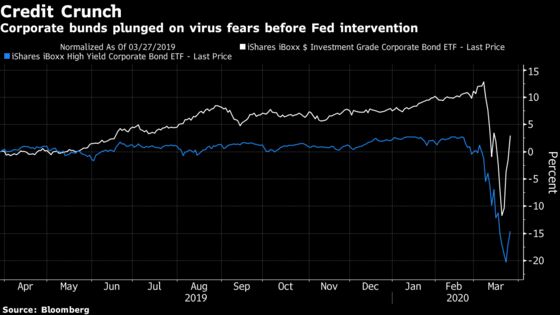

Bond ETFs showed signs of liquidity stress, with share prices trading at persistent and deep discounts to the value of the underlying assets. The historical volatility plaguing American bond markets created unprecedented dislocations in the ETFs that track them and threw off the market makers who normally step in to repair price inconsistencies. In theory, the price of all of an ETF’s shares should be exactly the same as the value of its net assets. In practice, it’s not uncommon for what’s known as the Net Asset Value (or NAV) to drop below the share prices, but such small discrepancies are usually quickly wiped away.

6. What did that do?

As the coronavirus outbreak unleashed historical turbulence in financial markets and liquidity dries up, ETFs spanning the bond spectrum began trading at steep discounts. Some of the hardest hit were iShares iBoxx $ Investment Grade Corporate Bond ETF, or LQD, and iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond, ticker TLT. That prompted worries that investors scrambling to redeem their holdings would overwhelm the managers, or the traders who channel bonds into and out of the funds -- worries that apparently led the Fed to act.

7. What did the Fed do?

The turmoil led the U.S. Federal Reserve to support corporate bonds and eligible credit ETFs in March, sparking a rally and unprecedented bond issuance. Since then, all-in investment-grade yields returned to pre-pandemic levels, and the ETFs that buy those bonds erased earlier losses. In addition, investment-grade companies broke the record for debt sales for two months in a row. The Fed’s Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility began purchases of eligible exchange-traded funds invested in corporate debt in mid-May with the largest corporate bond ETF surging the most in a month that day. Still, much of the enthusiasm from the Fed’s intervention announcement had already been priced in by that point, and the crisis seemed long past.

The Reference Shelf

- The Fed’s statement on the launch of its ETF-buying facility.

- The SEC’s report on Aug. 24, 2015 volatility.

- Do ETFs Increase Volatility? Working paper from the U.S. National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Investment Company Institute paper on how ETFs work.

- A U.S. Federal Reserve study looked at whether leveraged ETFs could contribute to market volatility.

- A Bloomberg News article about an ETF market maker shows how new funds are created.

- A Bloomberg Brief newsletter on the ETF industry.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.