Why Havens Might Not Be Safe When Everybody Rushes In

The rush to haven assets like gold could be creating new sets of risks.

(Bloomberg) -- The coronavirus outbreak has set in motion a massive re-allocation of capital, as investors move money into so-called haven assets -- those thought to be safe in a global economic downturn. That’s brought turmoil in stock markets, record low borrowing costs for the U.S. government and higher prices for gold bracelets. It could also be creating new sets of risks. If enough worried investors pile into an asset class to drive its price high enough, and worst-case scenarios don’t come to pass, they may be locking in losses instead of avoiding them. The soaring demand for the safest asset of all, U.S. Treasuries, has even strained other markets as well.

1. I know what a haven is. What’s a haven asset?

Merriam-Webster defines a haven as a “refuge” or “a place of safety.” In the financial markets, “haven asset” is applied to a range of assets, primarily those whose values are expected to rise when global market sentiment sours into a so-called “risk off” environment. They usually behave counter-cyclically, or tend to appreciate when the business cycle is in a downdraft. For debt securities, it’s those also deemed to have no -- or little -- credit risk, meaning you’re assured of repayment when the bond matures. Haven assets are also expected to be very liquid, meaning they can be bought or sold in big sizes with ease nearly anytime.

2. What are some examples?

Here are some of the haven assets getting the most attention:

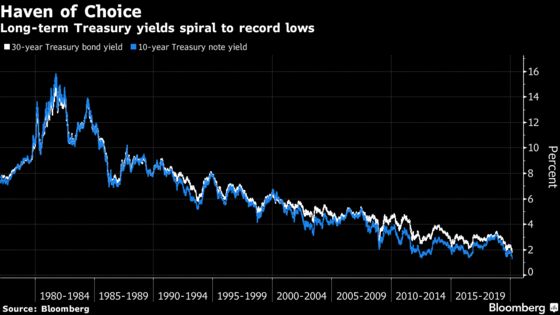

- U.S. Treasuries are the global safe-haven asset of choice, as nobody expects the U.S. to default on its debt obligations. America’s ballooning deficit over recent years has created an ample supply of about $16.7 trillion. The suddenly insatiable demand by worried investors for the securities has sent long-term Treasury yields to all-time lows. Germany’s government debt also falls into this camp, with investor demand driving yields on its bonds of all maturities below 0%.

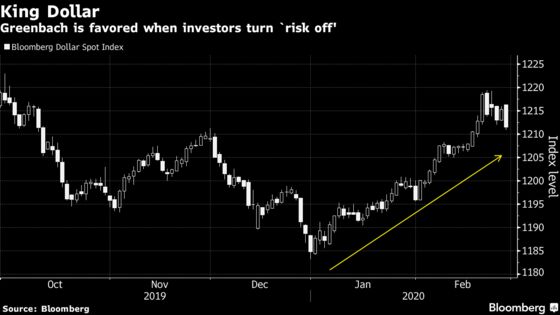

- Certain currencies. Among the more than $5 trillion in currencies traded each day, the U.S. dollar, Japanese yen and Swiss franc have tended to be favored havens (although not always, with the yen going a bit offsides lately). The International Monetary Fund has described currency havens as those from countries with relatively low interest rates and deep and liquid financial markets.

- Gold has long been a haven asset. When the prospect of strong returns elsewhere diminishes -- again think “risk off” -- gold becomes more attractive as a way for investors to get returns as the world sours. That’s why investor Warren Buffett says gold buyers are motivated by their “belief that the ranks of the fearful will grow.” Some people even have hidden gold underground, viewing it as the safest way to store their wealth.

- Within the world of stocks, avoided by many in a “risk off” period, some investors snap up lower-volatility shares and those of companies that produce goods that should remain in demand even if Armageddon arrives.

3. Are there risks when everybody does this at the same time?

Simple answer: yes! For starters, behind the rally in Treasuries lurks a potential disaster waiting to happen if any downturn gives way to a rapid rebound -- what’s known as a V-shaped recovery. That could send yields sharply higher and make prices tumble. That’s especially true because of the way so many investors have piled into long-term debt. The market’s growing duration -- a measure of how much prices will fall if yields rise -- is seen by some as a coiled spring ready to break. And dwindling liquidity in the Treasuries market has created volatility that’s made it harder for traders to establish the true value of the more than $50 trillion in assets that use them as a benchmark. The widening gap from models of fair value in years suggests that the odds are greater that prices snap lower than that they keep rising. And quantitative strategists warn that low-volatility stocks have become very richly valued.

4. What does this mean for people who aren’t traders?

There’s good news and bad news for them. Those in the market to buy a house now may be able to set their sights higher as tumbling debt yields have sent mortgage rates lower, and millions of Americans are expected to lock in lower monthly house payments by refinancing. On the flip side, this might be a good month for ignoring brokerage statements, given that $3 trillion has been wiped off the value of U.S. stocks.

The Reference Shelf

- A European Central Bank working paper on safe assets.

- International Monetary Fund paper on currency havens.

- A Bloomberg story on investors paying up for safety.

- A Bloomberg QuickTake explaining “Risk On” and “Risk Off.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Liz Capo McCormick in New York at emccormick7@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jenny Paris at jparis20@bloomberg.net, John O'Neil

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.