How Deutsche Bank’s Woes Infect All European Lenders

Why the News About Europe’s Banks Is Never, Ever Good

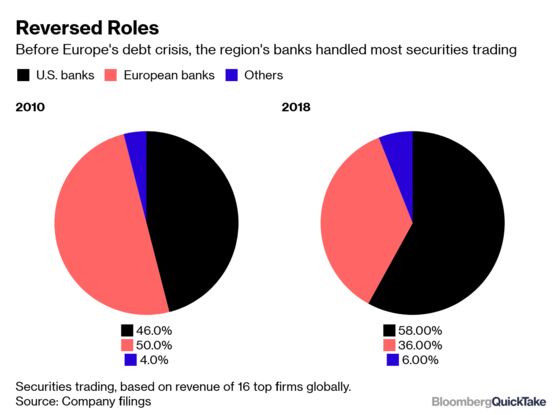

(Bloomberg) -- Europe has too many banks making too little money. The continent’s big lenders appear to lurch from crisis to crisis, burning through chief executives and seemingly endless resets of strategy. The flailing is particularly dramatic when compared with American rivals. A decade ago, Europe’s top five banks earned more than their counterparts across the Atlantic Ocean. By last year – when the top five U.S. banks raked in more than $100 billion in profit – their European equivalents earned just a third as much. With the global financial system increasingly intertwined, weak banks in Europe are a concern for banking systems everywhere.

1. What’s the problem?

Consider Deutsche Bank AG. Germany’s biggest lender, which once projected the nation’s financial might onto the global stage, has descended into a whirlpool of woes. Unable to reverse a spiral of declining revenue, sticky expenses and rising funding costs, the bank has lost money in three of the last four years. Chief Executive Officer Christian Sewing has embarked on a radical overhaul -- the bank’s fifth since 2015 -- to reshape operations by exiting businesses and slashing its workforce by a fifth. In April, government-brokered merger talks with local rival Commerzbank AG collapsed.

2. Is Deutsche Bank the worst off?

Yes, but that’s not saying much. Its large rivals are suffering from the same toxic brew of problems: competition from a crowd of smaller institutions and aggressive U.S. rivals, high costs, anemic revenue growth and a political landscape that’s hostile to cross-border consolidation. By early 2019, Europe’s lenders faced new economic headwinds, as Germany and Italy briefly teetered on the edge of recession. It’s no wonder so many strategic plans have come and gone. A new wave of scandals – most recently, over money laundering – and fines involving banks big and small have erased years of profits.

3. Why so many resets?

A decade after the 2008 global financial crisis, Europe’s big banks are still struggling with basic questions: What businesses do they want to be in? How much risk do they want to take? What kinds of clients do they want to serve and where?

4. How have they changed course?

France’s BNP Paribas SA and Societe Generale SA rolled out expansion plans, only to announce in February that they will shrink their securities units and cut costs. Britain’s Barclays Plc, on its third CEO since 2012, pulled back from riskier investment-banking activities, embraced them again and then came under fire from an activist investor to pull back once more. The biggest Swiss banks, UBS Group AG and Credit Suisse Group AG, have focused on the safer business of managing the fortunes of the wealthy. But those clients, spooked when geopolitical tensions increase volatility, have yanked assets.

5. Are the banks to blame?

Not entirely. In Europe, the economy recovered more slowly from the crisis than in the U.S., which used more aggressive measures to stimulate growth and forced banks to write off bad debts faster. And since 2014, the European Central Bank has held borrowing rates below zero to stoke the economy. That’s a persistent pain point, since banks are forced to lend at lower interest rates but will typically pay savers a rate slightly above zero to retain deposits, squeezing profit margins. In Europe, about 70% of financing is plain-vanilla bank lending. In the U.S., by contrast, a majority of companies raise money by selling stocks and bonds, enabling banks to earn fees even when lending margins are slim.

5. What’s the solution?

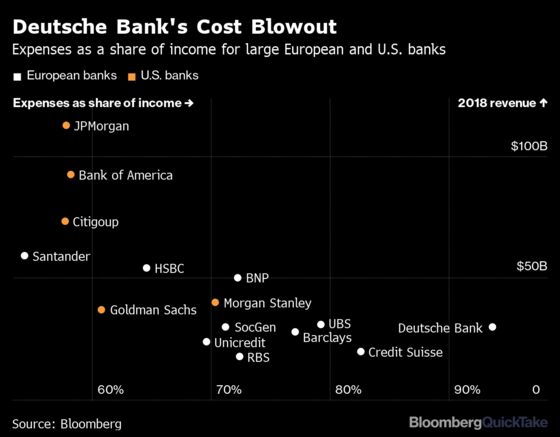

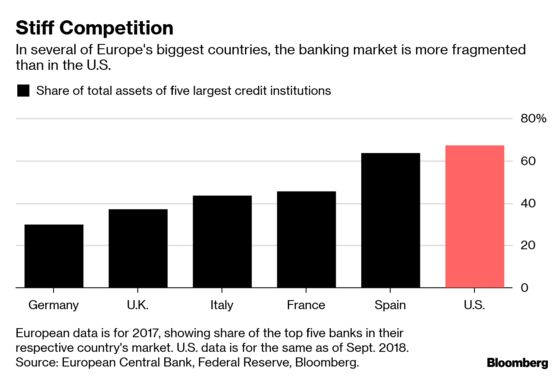

The most common refrain from bankers in Europe is that they’d be better off if they could get bigger. The industry is fragmented in France and Italy as well as in Germany, where banks share the market with a large number of government-backed and cooperative lenders. Those serve social and political goals, and they also make it hard for banks to turn much of a profit. Mergers might help reduce bloated expenses: The 10 biggest banks have costs that equal about 75 percent of income on average, compared with about 60 percent in the U.S., though their mix of business is somewhat different. They’re also investing in digital payment systems to compete with online rivals.

6. So mergers are the answer?

Maybe. The key question is what kind of mergers, and whether the best kind are even possible. Smaller lenders in Germany, Spain and Italy have been joining forces for a while now, but the barriers are much higher for the larger competitors, especially for cross-border deals that would bring more banks a continent-wide reach. The European Union is not a single financial market the way the U.S. is — the banks may do lots of international business but they’re all based in a single country. And while governments in Germany, France and the U.K. bailed out their banks during the 2008 crisis and protected them during the subsequent sovereign debt crisis, in return they’ve forced lenders to focus more attention on their home market. Plus no country wants to see a bank that’s regarded as a “national champion” be swallowed up by some other country’s champion. That’s particularly true in Germany, where banks provide critical trade finance to the country’s export-driven economy.

7. What else could get Europe’s banks out of this rut?

A lot of things, most of which seem hard or unlikely. Bankers had been hoping that the ECB would finally begin raising interest rates, but the economic clouds have pushed that prospect back and borrowing costs could be headed even deeper into negative territory. The ECB is considering a new round of low-cost loans to banks, known as TLTROs, to help lift the profits of lenders. The central bank has also been quietly lobbying in favor of cross-border mergers. And while EU officials have started work on building the institutions needed to underpin a broad and robust European market, like a common deposit insurance mechanism, progress has been slow and resisted by some members.

8. Will that be enough?

Maybe, but it’s hard to find a lot of optimists. This gloom is in sharp contrast to the way the future looked in the middle of the last decade, when it was European banks that were expanding onto the turf of their U.S. rivals and looked best positioned to become truly global institutions.

The Reference Shelf

- A QuickTake on Deutsche Bank’s whirlpool of woes.

- UBS Chairman Axel Weber on the need for mergers.

- Germany’s efforts to solve the Deutsche Bank problem aim to keep it within borders.

- How Europe’s political funk sets back its economy.

- The ECB’s policy of negative rates has created the "smell of panic," according to a report from Deutsche Bank’s head of research.

--With assistance from Grant Clark.

To contact the reporters on this story: Yalman Onaran in New York at yonaran@bloomberg.net;Donal Griffin in London at dgriffin10@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Sree Vidya Bhaktavatsalam at sbhaktavatsa@bloomberg.net, John O'Neil, James Hertling

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.