Why the Equal Rights Amendment, a 1972 Ideal, Is Back

Why the Equal Rights Amendment, a 1972 Ideal, Is Back

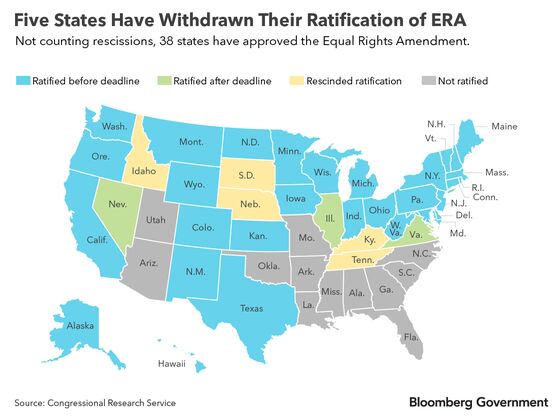

(Bloomberg) -- The push to amend the U.S. constitution to enshrine protections against sexual discrimination is back, almost half a century after the question was first put to the states. Advocates of the Equal Rights Amendment are mobilizing again now that 38 state legislatures, the number needed, have voted to approve it. The obstacles are considerable, including the inconvenient fact that the ratification deadline set by Congress came and went in 1982.

1. What is the Equal Rights Amendment?

It’s a proposed addition to the U.S. Constitution that the U.S. Congress approved in 1972. The key section is 24 words long: “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” If enacted, it would add sex to race and religion as attributes protected at the highest level of judicial scrutiny. As with all constitutional amendments, the ERA was sent to the states for ratification after winning the required two-thirds votes in the House and Senate. To take effect, it needed to be ratified by three-quarters of the union, meaning 38 states. Congress also chose, in the joint resolution proposing the amendment, to put a seven-year deadline on ratification.

2. What happened to the amendment?

Ratification initially moved quickly, with 35 state legislatures approving the ERA by the end of 1977. Then momentum stalled, and five of the ratifying states passed laws rescinding their approval of the amendment. With the original 1979 deadline looming, Congress passed a resolution to extend the deadline to 1982, but no additional states ratified it during that span.

3. Why is it being discussed now?

State lawmakers in Nevada brought the ERA back into the headlines by voting, in 2017, to make their state the 36th to ratify the amendment. In 2018, Illinois followed Nevada’s lead. And in January, following a Democratic takeover, Virginia’s legislature gave the ERA its long-awaited 38th ratification. That raised two legal questions: Is it too late, given the deadline set by Congress? (The attorneys general of Nevada, Illinois and Virginia have asked a federal court to declare the ratification deadline unenforceable.) And what about the five states that rescinded their ratification?

4. Didn’t the deadline for ratification pass?

Yes, and in the view of the U.S. Justice Department, nothing can change that now. Some say Congress can address the issue retroactively. The Democratic-controlled House of Representatives voted on Feb. 13 to extend the deadline, but the Republican-controlled Senate is highly unlikely to go along. Even if the resolution were to move through this or some future Congress, and got signed into law by Donald Trump or a future president, it would undoubtedly face court challenges. Whether Congress may retroactively extend or remove the deadline is one disputed issue. Another is whether a simple majority vote by Congress, like the one in 1978 that extended the original deadline, is sufficient to modify the conditions of a constitutional amendment.

5. How to account for states that have rescinded their ratification?

Neither the Supreme Court nor any federal appeals court has ruled on the validity of a state rescinding its ratification of a constitutional amendment. Complicating matters, the five state legislatures that withdrew support of the ERA used different approaches to do so. South Dakota, for instance, included language in its ratification resolution automatically rescinding it once the original 1979 deadline wasn’t met by enough states. Kentucky’s 1978 resolution to rescind its ratification was vetoed by the state’s lieutenant governor while the governor was on vacation out of state, leading both ERA proponents and opponents to claim victory. In Idaho, the legislature narrowly rescinded its approval over protests from some lawmakers that, like the initial ratification, rescission should require two-thirds majorities.

6. What’s the case for the Equal Rights Amendment?

Throughout the 20th century, advocates of such an amendment said it was a needed followup to the 19th amendment, which was ratified in 1920 and gave women equal voting rights to men. “Legal sex discrimination is not yet a thing of the past, and the progress of the past 60 years is not irreversible,” says a pro-ERA website maintained by the Alice Paul Institute, named for the suffragist considered the initial author of the ERA. “Remaining gender inequities result more from individual behavior and social practices than from legal discrimination, but all can be positively influenced by a strong message when the U.S. Constitution declares zero tolerance for any form of sex discrimination.”

7. What’s the case against it?

In the 1970s and 1980s, ERA opponents led by conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly and her Eagle Forum argued that the amendment would abolish privileges women already enjoyed, such as exemption from the military draft and advantages in child-custody cases. The Eagle Forum said last year that the ERA “would create a sex-neutral society that would erase women.” Conservative opponents also worry that the ERA, if enacted, would undermine restrictions on abortion and perhaps be used to give greater rights to transgender persons. “Since ERA does not define what ‘sex’ means, ERA would grant new constitutional protections of ‘strict scrutiny’ to all sexual orientation and gender identity laws and cases,” Anne Schlafly Cori, the current chairman of Eagle Forum, told Bloomberg Government in an email.

The Reference Shelf

- The 27 existing amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

- Reports from the Congressional Research Service on whether the ERA is close to adoption and the hurdles that could stand in the way.

- From Bloomberg Government, an analysis of the House resolution that seeks to remove the deadline for ratification.

- The text of the 1972 resolution that started the ERA debate.

- The pro-ERA website of the Alice Paul Institute.

- The Eagle Forum’s take on the harm the ERA would cause.

To contact the reporter on this story: Adam M. Taylor in Washington at ataylor239@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Heather Rothman at hrothman8@bloomberg.net, Laurence Arnold

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.