Thailand’s Junta Party Won the Most Votes. Now What?

Thailand’s Junta Party Won the Most Votes. Now What?

(Bloomberg) -- Coup-prone Thailand held its first election under a rewritten constitution on March 24 after the longest stretch of military rule -- nearly five years -- since the early 1970s. The vote doesn’t exactly presage a restoration of democracy and civilian rule, however. The military junta is seeking to bring its leader, Gen. Prayuth Chan-Ocha, back as prime minister. He represents an urban establishment that has long dueled for power with former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, who draws support from the rural poor, mostly in northern areas. Thaksin or his allies have won every election since 2001, only to be unseated by the army or the courts. As the country waits again for official election results, due by May 9, concerns mount about another bout of political gridlock and maybe even fresh unrest, further dragging on Southeast Asia’s second-largest economy.

1. How did the election go?

It was wild. In February a Thaksin-linked party stunned the country by nominating Princess Ubolratana Rajakanya as its candidate for prime minister. Her brother, King Maha Vajiralongkorn, quickly quashed that as unconstitutional, and the courts disbanded the party soon afterward. On the eve of the vote, the king, traditionally considered above politics, released a rare statement that in effect asked voters to back “good people” to keep out those seeking to ”cause trouble.” After the voting, the Election Commission unexpectedly delayed releasing some provisional results. Thaksin -- who went into self-imposed exile in 2008 to avoid trial on corruption charges that he says were politically motivated -- wrote in the New York Times that the election was “rigged” and that the junta “will find a way to stay in charge.” Days later the king revoked Thaksin’s royal decorations.

2. So who won?

It’s murky. Figures released by the Election Commission show the main pro-military party, Palang Pracharath, won the most votes out of more than 80 parties running. It says it will seek to form a coalition government with Prayuth as prime minister. The Thaksin-linked Pheu Thai party came second in total votes because it didn’t have a candidate for every district, but it appears to have won more seats in the 500-member lower house. So it also claims the right to try to form a government, and says it has built an alliance of anti-junta parties that would have a majority in the lower house.

3. Why did the military take over?

The 2014 coup, one of many since the absolute monarchy ended in 1932, followed a long effort by Thailand’s urban and royalist elite to curb the influence of Thaksin, a telecommunications tycoon first elected in 2001 on a populist platform and ousted by a coup less than six years later. Despite his decade-long absence, Thaksin retains a loyal following, particularly in the heartland where voters credit him with boosting crop prices and providing cheap health care. Detractors accuse him and his allies of vote-buying, fiscal recklessness and failing to do enough to tackle corruption. His sister, former Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra, also fled the country in 2017 rather than face jail in a criminal case related to a costly policy of paying farmers above-market rates for their rice crop. She also says the charges against her were politically motivated.

4. What’s different now?

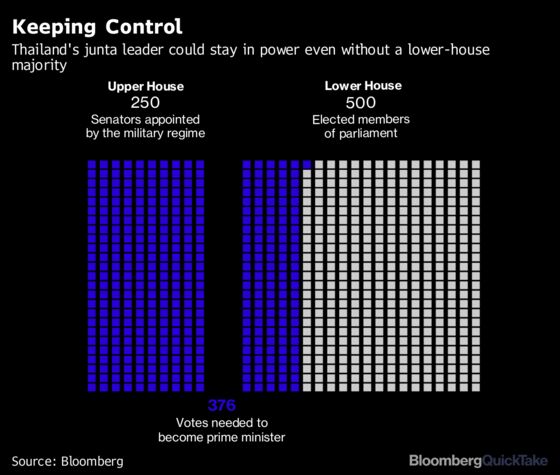

The new constitution, drafted by the junta, means the military will retain a decisive role in government. The 250-member upper house, or Senate, will comprise junta appointees and military brass. It can block legislation passed by the lower house. That’s on top of an unusual procedure for selecting a prime minister. In a typical parliamentary democracy, the leader of the party with the most seats in the lower house is tapped to head the government. In Thailand, any party that crosses the 5 percent threshold can nominate a candidate -- and members of both chambers get to vote, effectively tilting the playing field in the junta’s favor. A junta-backed candidate could sweep the Senate and then need just 126 votes in the lower house to make it to 376 -- the required majority.

5. So what outcome is expected?

A weak government, with a legislature divided into two camps, one against military involvement in government, and the other pro-junta, anti-Thaksin. These alliances represent the regional and class divides that persist in the country of 70 million people. Prayuth could easily return as prime minister with Senate backing: The party nominating him is expected to have about 119 seats. Another pro-junta party, Action Coalition for Thailand, likely won about five, and several others, with about 118 seats, are being courted. But without a majority in the lower house, his government would struggle to pass a budget or any other legislation.

6. What about Thaksin’s allies?

The anti-junta parties face possibly insurmountable hurdles with the Senate and the royal rebuke of Thaksin, which was seen as favorable for the pro-junta camp. In addition, the new constitution obliges future governments to adhere to the regime’s 20-year development plan, which took effect in October and covers national security, equality, development and other areas. Supporters say the plan will prevent graft and promote stability. Critics argue it further entrenches military rule. The bottom line: The new constitution gives appointed bureaucrats, soldiers and judges enough power to block any moves they don’t like.

7. Is that dangerous?

That sort of gridlock between the military and civilians could lead to the kind of street protests that preceded the recent coups. The late King Bhumibol Adulyadej, who died in 2016 after a 70-year reign, used his moral authority at times to resolve political crises. His son, the new king, will have a coronation ceremony May 4-6, days before the official election results are due to be certified.

8. Has the economy been affected?

The uncertainty hasn’t helped. Over the past decade of tangled politics, Thailand’s growth averaged 3 percent annually, well behind neighbors such as Indonesia and Vietnam. That compares with almost 4 percent over the preceding 10 years. The economy slowed sharply in 2014 around the political unrest and coup, and it remains to be seen whether a new government inspires investor confidence or revives memories of instability.

The Reference Shelf

- Profiles of the general-cum-politician and other candidates.

- A QuickTake on Thailand’s fragile democracy.

- A recap of the drama surrounding the nomination of the princess.

- Thaksin Shinawatra still casts a shadow in Thailand from exile.

- A look at what a return to civilian rule means for the economy.

- King Bhumibol’s obituary.

To contact the reporter on this story: Siraphob Thanthong-Knight in Bangkok at rthanthongkn@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Sunil Jagtiani at sjagtiani@bloomberg.net, Paul Geitner

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.