Why Qatar Is a Controversial Venue for 2022 World Cup

Why Qatar Is a Controversial Venue for 2022 World Cup

(Bloomberg) -- From its successful bid to hold the 2022 World Cup to its preparations for the monthlong tournament, Qatar has been a controversial choice. The scorching climate in the Persian Gulf country forced a switch from the usual summer slot to milder November and December. Investigations continue into how a tiny nation (population 2.7 million) with no soccer pedigree managed to win a secret vote to become host. While human-rights groups have decried the treatment of foreign workers, Qatar says the event is a catalyst for improving labor laws.

1. How did Qatar end up with the World Cup?

Ever since soccer ruling body FIFA in 2010 awarded Russia and Qatar the rights to each host a World Cup, allegations of vote-buying have swirled. (Two members of the 24-man FIFA executive committee that cast votes for World Cup hosts were suspended before the 2010 ballot after being filmed offering votes for cash.) While a FIFA probe into their bids cleared Russia and Qatar of wrongdoing, investigations continue in Switzerland and France, and a 2020 U.S. indictment accused three FIFA executive committee members of receiving payments to back Qatar’s bid. Qatar denies allegations of vote-buying. FIFA said awarding the event to the emirate was based on the organization’s strategy of expanding soccer into new regions.

2. What’s in it for Qatar?

Qatar is spending a record amount to stage the world’s most-watched sports event, with Bloomberg Intelligence estimating it’s on course to complete $300 billion of infrastructure projects before the Nov. 21 opening game. (Russia spent $11 billion on the 2018 tournament, which attracted 3.6 billion television and online viewers.) It’s a sum that Qatar — which is smaller in size than the U.S. state of Connecticut — is betting will showcase its push to become a tourism and business destination capable of taking on regional rival Dubai. The outlay (equivalent to more than $900,000 per citizen) is no huge stretch for Qatar, which with its vast reserves of natural gas is one of the world’s wealthiest countries. Qatar expects the World Cup to add $20 billion to the economy, equivalent to about 11% of the country’s gross domestic product in 2019.

3. Why the outcry over human rights?

Because of its treatment of more than a million poor, migrant workers, particularly from South Asia and Africa. A 2013 exposé in the British newspaper The Guardian revealed widespread exploitation of laborers helping to build World Cup infrastructure and reported that extreme heat and workplace accidents had led to high numbers of deaths. In 2019, the United Nations assailed Qatar for racial discrimination, saying a worker’s nationality plays an “overwhelming role” in how he or she is treated. The soccer preparations shined a light on the Gulf region’s “kafala” (sponsorship) system, under which workers need permission from their employer to switch jobs, return home or even open a bank account.

4. Anything else?

Labor rights aren’t the only issues that could draw international criticism. A Human Rights Watch report in March 2021 called for Qatar to pass rules that would defang the male guardianship system, a loose group of practices and rules that make many women’s personal decisions contingent on approval from a male family member. Homosexuality is officially illegal, but penalties are infrequently enforced and local World Cup organizers said they will allow displays promoting LGBTQ rights in stadiums.

5. How has Qatar reacted?

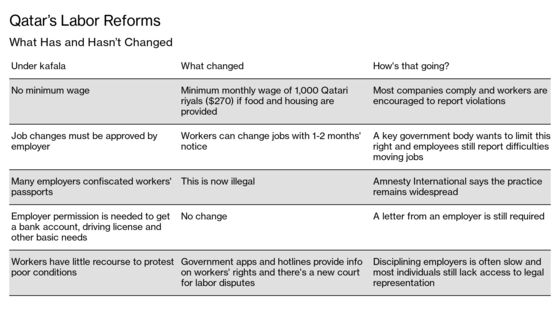

While Qatar refuted some specific allegations related to the treatment of laborers, authorities set about building new living quarters for workers and promised to improve safety. Qatar, whose workforce is 95% foreign, introduced new labor laws in 2020 meant to guarantee a minimum wage and make it easier to move jobs in what it says is an effort to dismantle the kafala system. At least on paper, the reforms make Qatar’s labor laws among the most worker-friendly in the Gulf.

6. Might there be boycotts?

Unlikely. There have calls for boycotts, including from leading players and teams in Norway and fans in Denmark. Norwegian soccer authorities rejected the idea in June. Before a World Cup qualifying game, the German national team lined up with a letter painted on each player’s top spelling out “human rights.” Groups such as Amnesty International have said enforcement of Qatar’s labor reforms has fallen short, but note the changes have been positive and pushed back on the idea of a boycott. Instead, they’re encouraging FIFA to demand implementation of labor reforms and for players to use their “star power” to promote rights.

7. How hot will it be?

Actually, the weather should be quite pleasant. The average mid-November high is 85 degrees Fahrenheit (29 degrees Celsius), and the heat tends to dissipate in December. Nonetheless, some of the tournament’s eight outdoor stadiums (seven of which are new) can be cooled with air conditioning systems, adding an extra challenge to FIFA’s pledge to make this World Cup carbon neutral.

8. What will it be like for fans?

No matter the weather, Qatar is a traditional Muslim society with modest clothing the norm. While there’s flexibility in five-star hotels, other public spaces including malls specify that women and men must cover their bodies from shoulders to knees. Public displays of affection are unwelcome; even hand-holding is rare. Alcohol is currently limited to restaurants attached to the swankiest hotels, though World Cup organizers have said tourists will be able to drink in designated “fan zones” and as part of high-end hospitality packages at stadiums. As for Covid-19, only fully vaccinated supporters will be allowed into stadiums, local media reported. Qatar is planning to purchase 1 million shots for visiting fans.

The Reference Shelf

- A QuickTake on the kafala system.

- A deep dive into Qatar’s building spree.

- A report from the UN Special Rapporteur on her visit to Qatar.

- Qatar’s World Cup website and FIFA’s page on how to get tickets.

- An Amnesty International report about workers’ rights in Qatar.

- A Guardian article on the American FIFA executive who took bribes to vote for World Cup bids before turning whistle-blower.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.