Why Protesters Are Back on the Streets in Thailand

Why Protesters Are Back on the Streets in Thailand

(Bloomberg) -- Thailand’s 2019 election was billed as an end to five years of military rule. Yet not much changed after the disputed vote: Former army chief and coup leader Prayuth Chan-Ocha returned as prime minister with the help of a military-backed party and the military-appointed Senate. After a court last year ordered an opposition party to disband, student-led rallies for more democracy gained momentum. Their demands have extended to the monarchy -- breaking taboos in a country where criticizing the king can land you in jail. Protesters have been trying to keep the pressure on despite a legal crackdown, adding to the woes of a government already struggling with a pandemic-induced economic crisis.

1. What are the protests about?

Much of the ire surrounds the constitution drafted by the junta ahead of the election, which all but guaranteed that the military-backed regime would retain control. Some groups want the charter rewritten, along with the election laws, to make them more democratic and reduce the military’s role. They also want the government to resign afterward and hold a new vote. And they have demanded an end to harassment of government critics such as the now-banned Future Forward Party, whose candidate for prime minister lost to Prayuth.

2. What about the monarchy?

In August 2020 one of the movement’s leading voices, Arnon Nampa, made a rare public call for rolling back measures enacted after King Maha Vajiralongkorn took the throne in 2016 that increased his power. Arnon has said that he wasn’t calling for toppling the monarchy, but that questions about its role needed to be raised. Students then issued a list of 10 demands including a clear separation between the monarch’s assets and those under the Crown Property Bureau, an agency that manages them for the palace no matter who is on the throne. There was also a call to “reduce the amount of the national budget allocated to the king to be in line with the economic conditions of the country,” which is suffering a deep downturn due to the coronavirus. Other proposed changes would ban the monarch from expressing political opinions, prohibit the king from endorsing coups and revoke so-called lèse-majesté laws that criminalize insults against the king and close family members.

3. What was the reaction?

Authorities are dramatically ramping up the use of the law against royal insults, which can result in a sentence of as many as 15 years in prison. Dozens of activists who participated in the demonstrations were facing royal defamation prosecutions, drawing criticism from United Nations rights experts. Arnon and Parit Chiwarak, the author of the 10 demands, have been arrested and released several times since mid-2020 on various charges. They and about a dozen other leaders charged with royal defamation were detained for weeks before being granted bail. Prayuth has questioned the movement’s funding and legitimacy, but said police wouldn’t use force against peaceful protesters. After several delays, the military-backed parliament in June approved a bill that would pave the way for a referendum on changing the constitution, as required before any overhaul. But for now, the lawmakers ignored the sweeping changes demanded by protesters in favor of a minor change to the election rules that would benefit big parties, including the one that backs Prayuth.

4. Who’s protesting?

Dozens of pro-democracy groups consisting mostly of young people and college students are leading the movement. They’ve been joined by labor groups as well as high school students chafing under military-style dress codes and gay, lesbian and transgender youths. There are no official leaders. Demonstrations have been held around the country and by October had grown to tens of thousands of people -- the biggest since the 2014 coup. (There was a lull during the coronavirus lockdowns but they returned in smaller numbers in June.) A poll taken in February found 20% of respondents said the movement was part of the democratic process, while 16% said it disrespected the laws. The survey of 1,315 people by the National Institute of Development Administration had a confidence level of 97%.

5. What’s the complaint about the constitution?

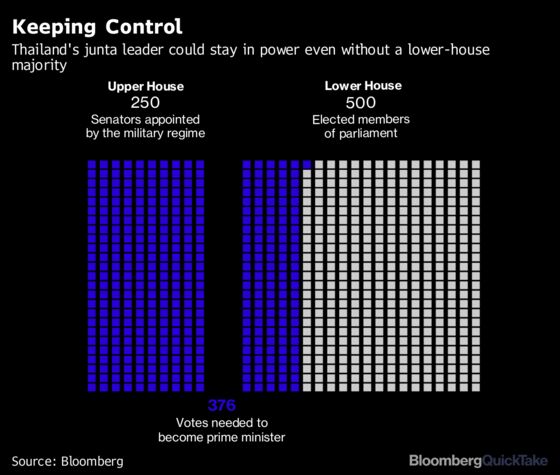

It set up a 250-member upper house, or Senate, comprised entirely of junta appointees and military brass, which can block legislation passed by the lower house. It also gets to vote along with the 500-seat lower house on prime minister, effectively tilting the playing field in the junta’s favor. (A junta-backed candidate can sweep the Senate and then win with just 126 votes in the lower house.) In addition, the new constitution obliges future governments to adhere to the old regime’s 20-year development plan, which took effect in 2018 and also covers national security. Supporters say the plan will prevent graft and promote stability. Critics argue it further entrenches military rule.

6. Why did the military take over in 2014?

That coup, one of many since the absolute monarchy ended in 1932, followed a long effort by Thailand’s urban and royalist elite to curb the influence of Thaksin Shinawatra, a telecommunications tycoon first elected in 2001 on a populist platform and ousted by a coup less than six years later. (He went into self-imposed exile in 2008 to avoid trial on corruption charges that he says were politically motivated.) Despite his long absence, Thaksin retains a loyal following, particularly in the heartland where voters credit him with boosting crop prices and providing cheap health care. Detractors accuse him and his allies of vote-buying, fiscal recklessness and failing to do enough to tackle corruption. His sister, former Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra, also fled the country in 2017 rather than face jail in a criminal case related to a costly policy of paying farmers above-market rates for their rice crop. She also says the charges against her were politically motivated.

7. What’s different now?

The grassroots nature of the protests are unusual for Thailand, where demonstrations over the past two decades have largely been backed by powerful political actors such as Thaksin or his rivals in the royal establishment. That presents a potentially greater challenge for Prayuth, who is struggling to rescue an economy that is heavily dependent on tourism and trade and can ill-afford political instability. Gross domestic product shrank 6.1% in 2020, according to the National Economic and Social Development Council, which forecast 1.5% to 2.5% growth this year. The king himself is relatively new, compared with the seven-decade reign of his revered father, King Bhumibol Adulyadej.

8. How did the election go?

It was wild. In February 2019 a small party stunned the country by nominating Princess Ubolratana Rajakanya as its candidate for prime minister. Her brother, the king, quickly quashed that as unconstitutional, and the courts disbanded the party soon afterward. On the eve of the vote, the king, traditionally considered above politics, released a rare statement that in effect asked voters to back “good people” to keep out those seeking to “cause trouble.” After the voting, the Election Commission unexpectedly delayed releasing some provisional results. Thaksin wrote in the New York Times that the election was “rigged” and that the junta “will find a way to stay in charge.” Days later the king revoked the royal decorations Thaksin still held. The winning governing coalition was led by Prayuth and the main pro-military party, Palang Pracharath, with a dozen or so smaller partners.

9. What’s the outlook?

The governing coalition has gained more seats in parliament by winning by-elections and persuading some lawmakers to cross the aisle. Prayuth survived a no-confidence vote in parliament on Feb. 20, the second since 2019. His government now has a strong majority in a legislature divided into two camps, one against military involvement in government, and the other pro-junta, anti-Thaksin. These alliances represent the regional and class divides that persist in the Southeast Asian country of 70 million people. The prospect of gridlock between the military and civilians leaves Thailand prone to political crises and coups.

The Reference Shelf

- A look at how Thailand’s new king has flexed his muscle.

- Bloomberg News looked at the wealth of the royal family.

- These charts explain why the country’s economic outlook is so dire.

- Bloomberg Opinion’s Clara Ferreira Marques sees the student-led protests straying into taboo territory, and looks at how social media undercuts autocrats.

- A profile of Prayuth, the general-cum-politician.

- QuickTakes on Thailand’s fragile democracy and its empty beaches.

- King Bhumibol’s obituary.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.