Why Polish Banks Face a Reckoning Over Franc Loans

Why Polish Banks Face a Reckoning Over Franc Loans: QuickTake

(Bloomberg) -- It was too good a deal to pass up. Starting more than a decade ago, Poles got the opportunity to take out mortgages denominated in Swiss francs with interest rates less than half the prevailing level for loans in Polish zloty. More than a million people jumped at the chance. Then in 2015, the Swiss unpegged the franc from the euro and it surged in value, just as the zloty was weakening. Some loans doubled in zloty terms, leaving homeowners struggling to pay. Thousands sued, and a European court has issued a ruling that may afford them relief. The long term impact on Polish banks could be severe, wiping out the equivalent of four years of profits.

1. What made mortgages in Swiss francs so popular?

For decades, Switzerland boasted some of the world’s lowest interest rates, so franc loans were a way for Polish and other eastern European consumers to escape high borrowing costs in their home countries. In 2008, mortgages taken out in zloty had average annual interest rates of about 8.7%, roughly twice that of similar Swiss-franc loans issued by Polish banks. As the global financial crisis pushed borrowing costs in Western countries toward zero, rates on new franc loans fell to 2.7% in 2010, central bank data show. The loans were offered by banks throughout eastern Europe, not just Swiss lenders. In Poland, non-zloty loans peaked at 198 billion zloty in 2011 and currently stand at 127 billion zloty ($32 billion) in total.

2. What’s happened to those mortgages?

With the zloty weakening to more than four against the Swiss franc this year (or about $0.25 per zloty) from highs of 2 in 2008, many of these Polish mortgages are now worth more than the underlying property -- meaning the homes are, financially speaking, underwater. (This plight also befell franc borrowers in Austria, Hungary and elsewhere.) So far there hasn’t been a flood of defaults on these loans because they’re mainly taken out for primary residences, not vacation homes, so people are prepared to do whatever it takes to pay them back regularly.

3. How many people are affected?

In Poland, about 450,000 households still have loans in francs or indexed to them, for a total obligation of $25 billion. The number, which has been dropping due to repayments, amounts to 24% of all mortgages and 14% of total loans to households, according to data from the Financial Supervision Authority. The plight of Swiss-franc borrowers, known as “Frankowicze,” has been front-page news in Poland for years. They have organized themselves into groups that attend parliamentary hearings, pressure politicians and stage protests to seek some form of financial relief.

4. What has the government done?

Starting in 2015, Poland’s financial regulator made it more expensive for banks to hold non-zloty mortgages by forcing them to set aside part of their profits to create capital buffers. The intention was to encourage banks to “voluntarily” convert Swiss-franc loans into zloty at terms acceptable to borrowers. This approach hasn’t worked, triggering frustration among mortgage holders and further lawsuits. The ruling Law & Justice party vowed to resolve the issue when it came to power in 2015 but has not managed to. In 2016, lawmakers debated legislation to aid the Frankowicze, but effectively abandoned the idea of forcing banks to convert the loans, which would have cost them billions of zloty.

5. What about the European court case?

One of the 8,000 lawsuits filed by Frankowicze alleging unfair loan practices came before the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg and was decided on Oct. 3. The ruling by the European Union’s top tribunal held that if Polish courts determine the mortgage contracts contain unfair terms, EU law would not block annulment of the loan agreements. The decision was seen as a partial victory for mortgage holders, but its application remains up to national courts in Poland that must now work their way through thousands of cases. If Polish courts follow the guidance of the ECJ, it could have sweeping repercussions for banks.

6. What exactly would it mean?

A July warning from the Polish Banking Association on the potential impact of an adverse decision sent shock waves through banks and drove down their share prices by as much as one-third. In the worst-case scenario for banks, the European ruling will trigger a further wave of Polish lawsuits and court decisions in favor of borrowers. That would force banks to book provisions that could spiral to as much as 60 billion zloty -- the equivalent of four years of profit for the entire Polish banking sector, or about 3% of its total assets, according to the Polish Bank Association. One central banker has called on financial regulators to consider reducing regulatory requirements to help lenders deal with growing legal risks.

7. Are all foreign currency loans similar?

No. About half of them are denominated in francs (or other foreign currencies) and the rest are only indexed to the Swiss currency. Depending on how loosely or strictly the EU verdict is interpreted by Polish judges, it could also affect loans denominated in francs. In August, Poland’s Supreme Court issued a non-binding opinion that also sided with borrowers, sending bank valuations to their lowest level in more than two years.

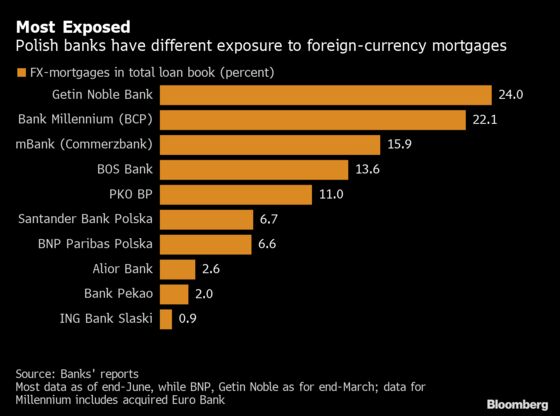

8. What are Polish lenders saying?

Most bank executives, especially those from lenders with hefty foreign-loan portfolios, have played down the risk of unfavorable court actions. A number have asserted that rulings forcing them to convert to zloty loans without being able to raise interest rates would be clearly unfair. So far, there hasn’t been a noticeable uptick in loan provisions taken by Polish banks. The government has said it doesn’t intend to bail out banks caught up in the situation, but it has tried to reassure markets by saying it has the tools to shore up lenders and maintain stability.

9. How have other countries responded?

In 2014, Hungary ordered banks to convert the equivalent of $14 billion in foreign-currency (mostly Swiss-franc) household loans to its national currency, the forint, at a set exchange rate and to offer some refunds to borrowers. A year later, Croatia’s parliament voted to force banks to absorb 6 billion kuna ($912 million) in currency losses by fixing the exchange rate at which banks switched their loans. In 2016, Romanian lawmakers approved a bill to convert Swiss-franc loans into leu at below-market rates, but the law was struck down as unconstitutional by a court and no longer applies.

The Reference Shelf

- Polish borrowers hail FX-loan victory as banks avoid the worst case.

- Slow bleed or incalculable risk? A guide to the Polish FX-loan ruling.

- Poland kicks off debate on easing safety buffers for banks.

- Investors start to wake up to zloty risks posed by FX-loans.

- Summary of the European Court of Justice ruling on Oct. 3, 2019.

- Advisory opinion to the European Court of Justice from May 14, 2019.

--With assistance from Konrad Krasuski.

To contact the reporter on this story: Maciej Martewicz in Warsaw at mmartewicz@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Wojciech Moskwa at wmoskwa@bloomberg.net, Piotr Bujnicki, Andy Reinhardt

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.