Why Delhi Is Becoming the Smog Capital of The World

Millions of Indians are breathing in the world’s most toxic air.

(Bloomberg) -- Millions of Indians are breathing in the world’s most toxic air. Each winter, thick smog envelops the capital of New Delhi and numerous cities across the dusty and densely populated North Indian plains. Air pollution in the New Delhi metropolis -- home to 20 million people -- has proved especially stubborn in 2019, and especially potent: One measure of pollution exceeded World Health Organization daily recommended limits by a factor of more than 20. An estimated 1.24 million people died in 2017 from India’s dirty air -- an annual catastrophe that the country’s authorities are struggling to contain.

1. What causes the pollution?

Vehicle and industrial emissions contribute year-round, as do road and construction dust and domestic fires lit by the poor. But a grim extra wallop comes late in the year from the burning of crop stubble, which continues despite being banned in the surrounding states of Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Haryana and Rajasthan. Farmers traditionally clear fields by burning in preparation for the winter season. Compounding the problem: The trough-like topography of north India means polluted air lingers in colder months.

2. What is the point of stubble burning?

After rice, wheat or other grain is harvested, the straw that remains is called stubble, and it must be removed before the next planting. It once was used as cattle feed, or to make cardboard, but harvesting by combine (rather than by hand) leaves 80% of the residue in the field as loose straw that ends up being burnt. Disposal by means other than burning -- such as plowing it into a fine layer of field cover -- costs time and money, two things that farmers say they can’t afford.

3. How serious is the health risk?

The Lancet estimated that 13% of India’s deaths are attributed to bad air. Researchers found 77% of India’s 1.4 billion people were exposed to air that way exceeded recommended limits, with the poor the worst hit. The most dire threat to humans is from PM 2.5, the fine, inhalable particles that lodge deep in the lungs, where they can enter the bloodstream. World Health Organization guidelines say exposure to PM 2.5 above 300 micrograms per cubic meter is hazardous; New Delhi’s average reading for Nov. 3 topped 500.

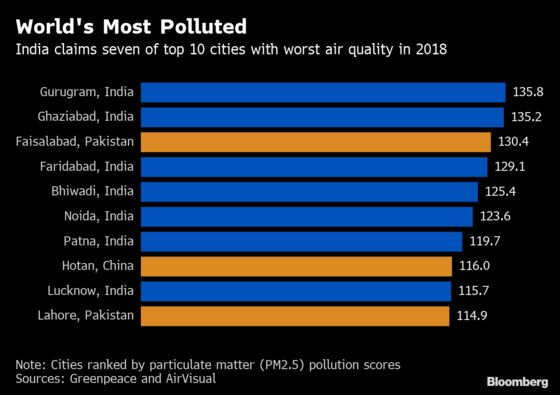

4. Where else in India is pollution a serious problem?

India was home to seven of the top 10 most-polluted cities in the world in 2018, as measured by PM 2.5, in a study by IQAir AirVisual and Greenpeace. Five of the top six -- Gurugram, Ghaziabad, Faridabad, Bhiwadi and Noida -- are close to Delhi state’s border. New Delhi, which is ranked 11th in the list, has been forced to shut down schools, cancel flights and encourage residents to stay indoors as pollution nears record levels.

5. Why not strictly enforce the ban on burning?

Farmers are a strong electoral constituency, and many argue that it is cheaper to burn the crops than rent equipment. India’s environment ministry said in 2018 that the ban was proving more effective and that the number of fires had fallen ahead of peak burning season in late October and early November that year. Yet in 2019, crop stubble burning continues. The Supreme Court has ordered immediate steps to curb the field fires while expressing shock at the inability to tackle the problem.

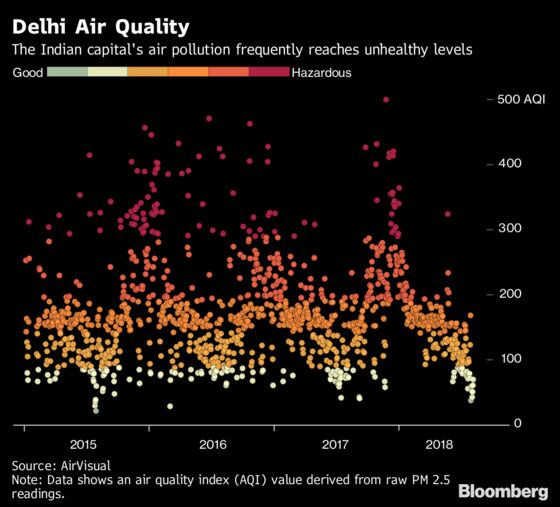

6. Does the problem end when the burning stops?

The worst of the pollution typically dissipates as spring begins, but New Delhi’s air remains dirty all year. This year, New Delhi residents breathed less than a week of air deemed “good” under U.S. Environmental Protection Agency guidelines, according to U.S. embassy data through Nov. 5.

7. What action is India taking?

Unlike in China, where the one-party state has directed a concerted nationwide anti-pollution drive, India’s various levels of government have struggled to make similar progress. The Supreme Court in 2016 mandated government action such as banning construction as pollution levels reached thresholds. The federal government says it’s now following a national clean air strategy, but activists criticize it for lacking hard targets and clear compliance mechanisms. On the positive side, New Delhi closed down its Badarpur coal-fired power plant and has taken small steps such as cracking down on polluting vehicles, banning use of dirtier fuels and curbing construction activities. The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party has pledged to reduce levels across 102 most polluted Indian cities by at least 35% over the next five years. Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal campaigned this year with a manifesto to make all buses electric and even to vacuum roads.

8. What’s the impact on the economy?

By the World Bank’s calculations, health-care fees and productivity losses from pollution cost India as much as 8.5% of GDP. At its current size of $2.6 trillion that works out to about $221 billion every year.

9. What more can India do?

Critics say it should more quickly coordinate antipollution efforts across all levels of government and boost resources to enforce rules such as the crop burning ban and limits on dust at construction sites. Continuing to adopt cleaner fuels such as compressed natural gas and introducing policies to rapidly boost electric car usage would also help, as would strengthening the public transport system to reduce the number of vehicles on the road.

10. How are citizens reacting?

There’s been no major outcry yet beyond social media griping. People continue to set off fireworks, ignoring a Supreme Court ban and warnings from doctors about the health risks. Meantime, sales of air purifiers and face masks are rising and indoor plants have become a popular feature of New Delhi homes.

The Reference Shelf

- The world’s fastest-growing economy has the world’s most toxic air.

- India’s anti-pollution efforts may be stymied by poor monitoring.

- A QuickTake explainer on China’s smog and the global menace of air pollution.

- This is Pakistan’s problem, too.

- Bad air means good business for some.

- The WHO’s air pollution database.

- Towards a Clean-Air Action Plan. A report by India’s Centre for Science and Environment.

--With assistance from Pratik Parija.

To contact the reporters on this story: Debjit Chakraborty in New Delhi at dchakrabor10@bloomberg.net;Rajesh Kumar Singh in New Delhi at rsingh133@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Unni Krishnan at ukrishnan2@bloomberg.net, Grant Clark

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.