Why Liquidity Is a Simple Idea But Hard to Nail Down

Why Liquidity Is a Simple Idea But Hard to Nail Down

(Bloomberg) -- In the financial world, liquidity is cited constantly but rarely explained. It’s a term used in different ways depending whether the subject is economics, markets or banks. Regardless of which context, an old market adage often rings true: Liquidity is a coward that disappears at the first sign of trouble.

1. What is liquidity?

Think of it as the opposite of friction. An asset’s liquidity is a measure of how easily its value can be converted or transferred into another form. Cash is the ultimate liquid asset. Freeing up the value of less-liquid assets takes time or money or both – paying for something by selling a car isn’t as easy, quick or cheap as using a $5 bill to buy coffee. But liquidity is about more than individual assets.

2. What else then?

The markets in which such transactions take place vary in their liquidity –- that is, in how cheap or easy it is to find someone to participate in the transaction. Big stock markets are almost always highly liquid: It’s easy to quickly find a buyer or seller. The high volume of stock trades with publicly posted prices means that the gap between what the two parties think an asset is worth – known as the bid/offer spread – is generally small. At the other extreme lies, say, real estate where a small number of interested parties makes determining the fair value of a property harder. At times of financial stress, markets that are usually liquid can resemble those of real estate, or worse. That happened during the global financial crisis, when holders of mortgage-backed securities struggled to accurately price and sell them as defaults rippled through. Another measure of liquidity, which is often talked about in financial systems, is the availability of cash for transactions. The less cash, or cash-equivalent assets, there is, the harder it is for deals to be done.

3. Why is that?

Liquidity depends on having the money you need now, as well as what you think you’ll want in the future, whether by borrowing or selling. If companies can’t get hold of funds to pay their debts, they may have to dump assets at what are known as fire-sale prices -– a step that hurts other market participants by driving down the value of their assets. Liquidity also depends on trust. If a bank doesn’t trust money it lends through interbank markets will be repaid, it will cut back on its lending or demand higher rates -– which makes other banks’ liquidity situation worse as they have less access to credit.

4. How can you tell if liquidity is a problem?

There are a few indicators that track the various ways that companies and banks fund themselves. These metrics often come down to looking at the difference in the cost of borrowing for two entities, what’s known in traders’ lingo as funding spreads. For instance, on the economic data front, M2 money supply offers a measure of money in the system while bank lending survey data provides insight on household demand for credit. There’s also so-called excess liquidity, which shows all the extra funds sloshing around the banking system on top of what’s needed for regulatory reasons.

5. What about in credit markets?

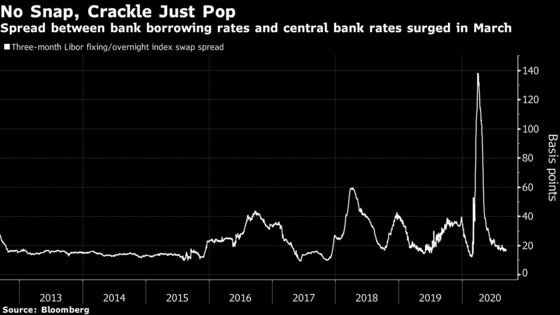

Some common credit market gauges reflect the difference between rates set by a central bank and the rates banks must pay to borrow. In the U.S., that means comparing the federal funds rate -- the tool by which the Fed manages short-term interest rates, which is regarded as a proxy for safe borrowing -- and Libor rates, which reflect what banks report charging one another for loans. This measure is known as Libor/OIS, or FRA/OIS in futures markets, and an elevated reading means there’s less willingness to lend, meaning that the market can be considered less liquid. Another popular measure of liquidity is the difference earned in locking up funds for short and longer periods. This can be seen in the spread between one- and three-month Libor, with investors demanding much higher returns for lending funds for longer. In the stock market, a widening of bid/ask spreads can be an indication that trading is less liquid.

6. What does this mean for traders?

Portfolio managers want to hedge against any sudden tightening of liquidity. They often do that by buying contracts tied to FRA/OIS spreads, which lets them position themselves against the cost of interbank lending rising relative to central bank rates. Or alternatively, they might buy government-issued bonds against interest rate swaps, which carry counterparty risk. Such trades have what’s sometimes referred to as a convex payoff ratio, they can pay off handsomely if spreads move wider, with limited losses if there’s no change in the backdrop.

7. How do companies deal with market liquidity?

Large corporations fund many of their day-to-day operations through what amount to short-term IOUs in what’s known as the commercial paper market. Comparing rates on commercial paper to overnight index swaps, another proxy for central bank rates, is another key metric. This part of the market came to the forefront in March as companies across the globe rushed to build up cash buffers to weather the economic fallout of the coronavirus outbreak. Firms worried about their liquidity in the tough times ahead engaged in what was called a “dash for cash.” They drew down their credit lines at banks and turned to commercial paper markets, sending these rates sharply higher before the volumes plummeted as buyers of the paper stepped back and this market began to operate in crisis mode.

8. What happened then?

As borrowing spreads widened, the rush to raise cash intensified, leading fund managers and foreign central banks to sell Treasuries, widely regarded as the most liquid asset after cash. But this rush created a domino effect in liquidity: the dealers who act as market-makers soon became overwhelmed, as their Treasury holdings shot to record heights. This jammed up dealers, leaving many with limited ability to make markets in Treasuries or other key funding markets. Short-term borrowing rates spiraled.

9. How did that get resolved?

Given the severity of the consequences of a major liquidity crunch, central banks are quick to step in at times of stress, such as in March. The U.S. Federal Reserve announced a series of measures to keep funding markets functioning, including increasing the amount of cash offered to borrowers in the so-called repo markets, where banks and other big investors swap Treasuries and other securities for cash, often only overnight. This allowed dealers to turn Treasuries into reserves, easing the crisis. The Fed also reactivated a series of tools from the 2008 financial crisis to support short-term credit, and beefed up dollar swap lines that helped other foreign banks avoid a squeeze on their dollar borrowings.

The Reference Shelf

- QuickTakes on the FRA-OIS spread and the turmoil in 2019 in the repo market.

- An article in the Bank for International Settlements’ bulletin on the pandemic’s disruption of credit markets.

- The New York Fed’s Liberty Street Economics Blog on interventions in the repo market.

- A Bloomberg News article on the little-known trade that crushed liquidity in the Treasury market in March.

- Bloomberg News runs a daily Markets Liquidity Watch column; terminal subscribers can find it at {NI LIQWATCH

}.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.