Why Leveraged Loans, CLOs Feed Worries in Virus Slump

Why Leveraged Loans, CLOs Feed Worries in Virus Slump: QuickTake

(Bloomberg) -- Higher-risk corners of the financial market are under stress from the economic collapse caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. One area that’s a focus of intense nail-biting is so-called leveraged loans -- or borrowing by companies with shakier credit ratings. As prices of these loans plunged in March, concerns grew about a wave of credit-rating downgrades or defaults. What’s more, the securities are packed into investment vehicles called collateralized loan obligations, or CLOs, creating the potential for a worrying ripple effect.

1. Why worry about leveraged loans?

When the pandemic triggered an extended economic shutdown, attention turned to companies that could face a squeeze and supercharged debt bets that could quickly sour. Leveraged loans are inherently risky and the market has boomed in the past 10 or so years. The securities have been a magnet for investors in an era of low interest rates. But the market has also been prone to bouts of volatility, even as its total size topped $2 trillion. The loans offer financing to companies that have shaky credit ratings because they have a lot of debt relative to income and cash flow.

2. Why are CLOs a worry?

CLOs have been likened to collateralized debt obligations, or CDOs, which became famous for melting down in the 2008 financial crisis. While it’s a comparison the market dislikes, both are structured products created by pooling assets to create new securities. While CDOs cover a wide array of debt, CLOs are built from leveraged loans. They’ve become a big part of financing corporate America -- about 60% of loans to sub-investment-grade firms are folded into CLOs. While the downgrade of an individual loan likely won’t damage a CLO’s ability to pay investors, a deluge of them around the same time certainly could. Still, there’s a debate. CLOs fared well in the 2008 crisis, with none of the highest-rating tranches defaulting.

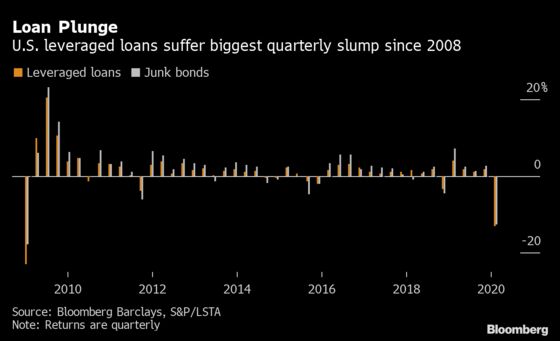

3. What’s the market telling us about leveraged loans?

Prices for U.S. leveraged loans trading in secondary markets plunged 13% in the first quarter as the virus took hold, reaching levels not seen since 2008. On April 2, the benchmark index stood at 83 cents on the dollar, after recovering somewhat from a quarter-low of 76 on March 23, when stock and bond markets were all in freefall. (It hit an all-time low of 61.7 at the end of 2008, according to data from Standard & Poor’s and the Loan Syndications and Trading Association.) Market-watchers are predicting a wave of defaults, saying that investors could recover some 55 cents to 60 cents for each dollar they invested.

4. Could leveraged loans be rescued?

Probably not directly. Wall Street regulators have discussed ways they could help the leveraged-loan market by, say, relaxing lending guidelines to make it easier for banks to extend additional financing to troubled companies. The U.S. Federal Reserve has taken steps to keep liquidity flowing to the corporate debt market and relaxed regulatory requirements on bank capital. Short term, banks are providing support by ensuring access to so-called revolving credit lines. Longer term, though, more companies will likely face trouble. The Fed, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. have limited reach into the leveraged-loan market, because much of the riskiest financing has been provided by credit funds and so-called shadow banks that they don’t directly regulate.

5. Why are leveraged loans so attractive?

Investors are attracted by their higher returns -- leveraged loans returned about 8% in 2019. In the credit market, non-investment-grade, or so-called junk bonds have traditionally gotten the bulk of attention. But if a borrower defaults, leveraged loans are likely to recover more money because they typically rank ahead of bonds in bankruptcy proceedings. The money raised by leveraged loans was used to do things like fund buyouts by private-equity firms, pay shareholder dividends and refinance borrowings. They are typically secured by assets and have a Moody’s credit rating of Ba1 or lower or S&P rating of BB+ or lower.

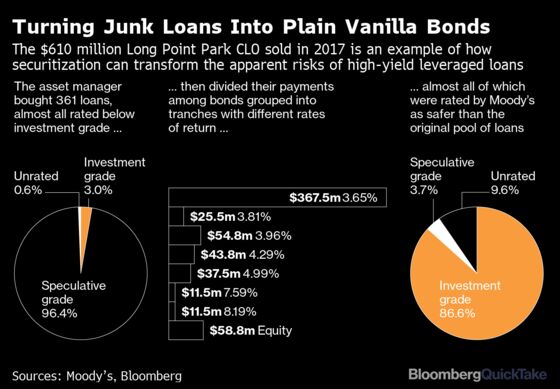

6. How does a CLO work?

Typically, an asset manager or an asset management arm of a bank buys 100 to 350 loans, sometimes more. The loans are packaged into bonds in groups, or tranches, representing different risk and return. The highest-ranking tranches have first dibs on the cash flow generated by the underlying loans, but also have lower returns. The riskiest but potentially most lucrative layer of a CLO is known as the equity tranche, which is last in line to receive cash flows but the first to realize losses.

7. Who buys them?

While CLOs are sold globally, 75 percent of the market is U.S.-based. The U.S. CLO market has more than doubled since 2008, growing to about $670 billion in outstanding debt. The biggest issuers include the likes of Blackstone’s GSO, CIFC Asset Management, PGIM Inc. and Credit Suisse Asset Management. Insurance companies, pension funds and banks are big buyers; Wells Fargo & Co., JPMorgan Chase & Co., and Citigroup Inc. are the largest holders of U.S. CLOs, according to Citi research. (There’s also a significant Asian market, with Japan’s Norinchukin Bank and Japan Post among the big buyers.)

8. What’s the appeal of CLOs?

Wells Fargo said in a March 25 note that AAA CLO notes paid spreads above benchmarks in the mid-to-high 300 basis point area, meaning an extra 3 percentage points in return. A similarly rated corporate bond paid about 142 basis points more than its benchmark on the same date. Another part of the appeal of CLOs is that both the underlying leveraged loans and the CLO bonds have floating interest rates, meaning they generate higher yields as rates go up, unlike most corporate bonds. In some ways, CLOs have gotten safer since the last financial crisis: they have more of a buffer between the value of the loan pool and the value of the debt, known as over-collateralization, among other tests designed to shield investors from losses. The industry also points to the diversity of loans CLOs hold, making them less susceptible to collateral damage -- literally. So if one industry gets hammered, the way the energy sector was in 2015 and 2016, stronger areas of the economy could make up for it.

The Reference Shelf

- How trades with extreme leverage are suddenly getting tested by the Covid-19 pandemic.

- A look at Wall Street’s “CLO machine” and the fortunes it made.

- The Financial Stability Board’s report published in 2019 on non-bank financial intermediation.

- How CLO managers prepared at the start of 2019 for a possible economic downturn.

- A top Federal Reserve official’s 2018 warning that CLO investors may be taking on too much risk.

- Related QuickTakes on the history of leveraged loans and CLOs, plus how they’re different than junk bonds and why they’re loved by Japanese investors.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.