Why Investors Are Spooked by GE's Giant Debt Load

Why Investors Are Spooked by GE's Giant Debt Load

(Bloomberg) -- General Electric Co., one of the most storied companies in U.S. history, has had a bumpy ride with its turnaround. The latest challenge for the new chief executive is to calm fears in the credit market after ratings were cut on struggles at the company’s power unit, whose weakness has been putting significant pressure on cash flows. It’s a crisis that’s being watched closely by the broader corporate bond market, where concerns about the build up of debt over the last few years are mounting.

1. Why has GE’s debt reached a crisis point?

Nervousness around GE’s debt has been growing since October, when S&P Global Ratings downgraded its credit rating two notches to BBB+, just three steps above junk. By the start of November, Moody’s Investors Service and Fitch Ratings had followed suit, sparking a tumble in the price of the company’s bonds that pushed several through all-time lows. New chief executive Larry Culp helped trigger the latest sell-off. In a rare interview, he sought to calm investors by expressing a “sense of urgency” in cutting debt and selling assets. This backfired, leading to a 10 percent price drop in the value of its shares on Nov. 12, similar moves in the company’s bonds, and a sharp rise in the price of derivatives that protect against losses in the case of a default. However, a sped up $4 billion plan to reduce its stake in subsidiary Baker Hughes on Nov. 13 helped reverse some of the latest falls of the company’s debt and equity.

2. How much debt does GE have?

Less than before, but still a lot. Debt totaled about $115 billion at the end of September, down from $135 billion at the end of 2017. Borrowings have been falling as the company has switched to selling assets and improving the state of its balance sheet, and tackling the legacy of General Electric Capital Corp., GE’s financial-services arm. GE has decreased its short- and long-term debt by around $300 billion since the end of 2010 as GE Capital has shrunk and assets have been sold off. Compare that to the company’s free cash flow, however, and the numbers are less comforting. According to company-reported data, GE’s free cash flow was negative $718 million in the nine months ended Sept. 30, 2018, as compared to positive $11 billion in the 2014 fiscal year.

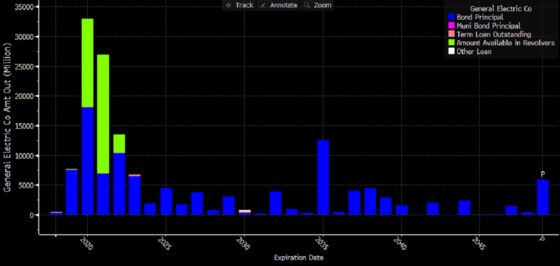

3. When does GE need to pay down its debt?

Companies with large debt loads typically need near-constant access to funding markets so as to be able to manage frequent refinancing needs, and GE is no exception. It has close to $8 billion of bonds due in 2019 and a whopping $25 billion in 2020 and 2021. The company has said it has a “sound” liquidity position, including cash and operating credit lines, and is committed to strengthening its balance sheet by reducing its debt. Its debt distribution looks like this:

4. Could GE face further ratings cuts?

That’s not clear, but the market is starting to price it in. While rating firms have indicated no downgrades are imminent, prices of the company’s credit derivatives and debt are closer to lower-rated securities. Yields on some of its bonds have reached levels in line with junk-rated bonds, Bloomberg Barclays index data show. And the company’s only actively traded preferred stock -- which sits just above common stock in the capital structure and currently holds an investment-grade credit rating -- yields more than some distressed credits. Moody’s analysts said Oct. 31 that the company’s free cash flow would be “very weak” in 2018 because of the performance of the GE Power unit, though this would be offset by a reduction in dividends to shareholders. The ratings agency warned that further downgrades might be possible if the company got weaker-than-expected support from investors for future debt issuance.

5. Why is this worrying the broader bond market?

As rates have risen, the credit market has been getting nervous about the many large firms that have loaded up their balance sheets with debt. There’s now around $3 trillion of borrowings rated BBB, the lowest rating bracket above junk, as low interest rates over the past several years encouraged firms to borrow cash to buy competitors. There are concerns that a lot of these companies might be rated junk already if not for leniency from credit raters. Scott Minerd, Guggenheim Partners’ chairman, crystallized these fears on Nov. 13 in a tweet saying GE “is not an isolated event” and that “the slide and collapse in investment-grade debt has begun.”

6. How did GE get to this point?

Some of GE’s struggles, and large debt burden, can be traced back to more than a decade ago, when its GE Capital unit required a bailout from the U.S. government and Warren Buffett. Since then its conglomerate model, where robust businesses are meant to balance out any problem units, has continued to misfire. Worse-than-expected results from its GE Power division have undermined positive results of better-performing businesses. That’s complicated efforts to push the company toward a smaller and simpler structure. Earlier this year it was kicked out of the Dow Jones Industrial Average index. Its market cap of about $72 billion is a far cry from the $400 billion figure when legendary CEO Jack Welch retired in 2001.

7. Is debt GE’s biggest problem?

The state of GE’s balance sheet is only one of a number of problems the new CEO has to deal with. The power business needs a fix, and there’s a significant pension shortfall, as well as a federal accounting probe. And as its stock has slid, so has the company’s reputation for managerial stability, rocked by the sudden departure of John Flannery after just a year in the role.

The Reference Shelf

- A stockholder apparently sold more than $333 million in GE shares in one fell swoop.

- Bloomberg Businessweek on how GE went from American icon to astonishing mess.

- GE investors keep hoping the stock has hit a bottom, writes Bloomberg Opinion columnist Brooke Sutherland.

- GE credit investors are snapping up derivatives that protect against losses on the company’s debt.

To contact the reporter on this story: Natalya Doris in New York at ndoris2@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Tom Freke at tfreke@bloomberg.net, ;Christopher DeReza at cdereza1@bloomberg.net, Randall Jensen

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.