Why India's Government and Central Bank Are Feuding

Why India's Government and Central Bank Are Feuding

(Bloomberg) -- The U.S. Federal Reserve is hardly the only central bank in the world feeling the heat from political leaders. The Reserve Bank of India has often been at odds with the nationalist government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, which since taking office in 2014 has periodically accused the bank of not doing enough to boost economic growth. With a general election approaching, the discord began to worsen markedly. However, signs of a truce -- perhaps just a temporary one -- have emerged.

1. How did the relationship deteriorate?

The long-simmering rift erupted anew in October when a top RBI official warned of “economic fire” if the bank’s independence were compromised. Finance Minister Arun Jaitley didn’t directly respond to the comments but a few days later criticized the central bank, saying it (and the previous government) “looked the other way” while banks lent indiscriminately in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. The government has also indicated it is looking at a never-used legal provision that could possibly lead to the state overriding the central bank’s decision-making if invoked, according to people familiar with the matter.

2. What’s at the heart of the dispute?

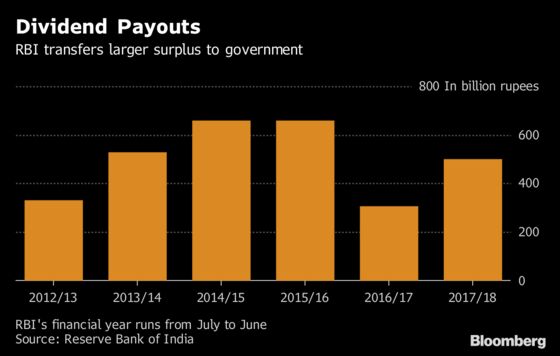

There are two key sticking points: restrictions on banks and the central bank’s reserves. RBI Governor Urjit Patel has continued the bank’s push for more powers to clean up a banking system that’s saddled with bad debts. Already, the central bank has fenced off 11 weak, state-run banks, placing curbs on lending, new branches and dividend distributions “to prevent further hemorrhaging of their balance sheet” while they are nursed back to health. The government -- the biggest shareholder in 70 percent of the country’s banking system --wants some of these strictures eased in a bid to kick-start lending that it hopes will support growth. The government has also been asking the RBI to relax tougher capital requirements for banks to free up more resources to lend. On the central bank’s reserves, Modi’s administration wants a bigger slice of the pie to be transferred to the government to help fund its budget goals.

3. What’s the backdrop?

Modi is seeking re-election in early 2019 as the country grapples with higher oil prices, slowing exports and cooling domestic demand, among other issues. Patel, who has a doctorate in economics from Yale University, will see his term expire in September 2019, and local media have begun speculating about whether he will stay on for a second. Patel rose from deputy in 2016 after his predecessor, Raghuram Rajan, decided to head back to the University of Chicago after only one term. Rajan had faced criticism from a prominent Modi ally who accused the former IMF chief economist of keeping interest rates too high. Many bankers also complained about Rajan’s aggressive efforts to clean up bad debt at state-owned lenders.

4. What’s the truce?

The central bank signaled a compromise after a marathon board meeting on Nov. 19. Although the board retained the capital buffer ratio at 9 percent, it gave banks more time to meet the requirement. According to economists at Nomura Holdings Inc., the meeting pushed the contentious issues onto the back-burner and helped preserve the RBI’s autonomy.

5. What are the other bones of contention?

- MONEY: As mentioned earlier, the government wants the RBI to part with more of its reserves. The central bank says it needs to strengthen its balance sheet. At the end of the board meeting on Monday, the RBI said a committee will be set up to look into the central bank’s capital framework. Last year, the RBI was pressed to cough up another 100 billion rupees ($1.4 billion) after paying a dividend of 306 billion rupees, the lowest in five years.

- BAD LOANS: The RBI has long tried to get state lenders to recognize soured loans, particularly to the power sector. According to Bloomberg Opinion’s Andy Mukherjee, the Modi government hasn’t exactly cooperated. It even recently appointed an RBI critic to the bank’s board who in a speech last week criticized globalization and chided the monetary authority for being too tough in its efforts to get rid of bad debts. Two years ago, he suggested Western-educated elites wanted to weaken Indian lenders by forcing them to come clean so that they could be sold to foreigners.

- DEADBEATS: The central bank has been leaning on bank managers to cut off “willful defaulters” -- borrowers who have stopped servicing their debt even though they have the ability to pay. This year it introduced rules forcing lenders to declare a borrower delinquent as soon as payments were a day late. Government and power company officials have lobbied against the rules, and in September the top court temporarily halted legal proceedings against some power producers declared delinquent.

- TURF: A government panel has recommended an independent regulator be created for a payments system, primarily because it views digital payments as separate and independent from the more traditional sector. The RBI, citing the international model, argues the payments regulatory board must remain with the bank and be headed by its governor.

- EXPECTATIONS: In 2017, then-Chief Economic Adviser Arvind Subramanian criticized forecasting errors by the central bank as “large and systematically one-sided in overstating inflation.” Inflation has recently undershot the RBI’s projections but the central bank has shifted its policy stance toward tightening.

The Reference Shelf

- QuickTakes on India’s debt recovery, India’s coming election and central bank independence.

- India’s central bank stares down rupee’s slide.

- Modi’s shock takeover of a risky lender.

To contact the reporter on this story: Anirban Nag in Mumbai at anag8@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Nasreen Seria at nseria@bloomberg.net, Grant Clark

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.