Why FPOs Are Taking the Wind Out of Tech IPOs

Why FPOs Are Taking the Wind Out of Tech IPOs

(Bloomberg) -- It used to be that technology company initial public offerings (IPOs), were as exciting and potentially enriching an event as the markets had to offer, as investors fought to get in on the ground floor of a hot startup. Now there’s a different ground floor: the final private offering, or what some in technology circles are calling an FPO. These late-stage venture capital funding rounds are attracting increased interest from a wide range of other big investors. The demand comes as startups stay private longer, making an FPO a way to buy a stake in a more mature company before those companies enter public markets.

1. What happens during an FPO?

Like IPOs, FPOs also raise money by issuing new stock, but they do so on the private market. In addition to gaining the money companies need to fuel their growth, these private deals can also let insiders and other early investors sell some of their existing shares. (Confusingly, FPO is also an acronym for follow-on public offerings, a new issue of stock from a company that’s already held an IPO.)

2. How is this different from normal fundraising?

There’s no strict definition of an FPO versus a typical venture-capital financing round, and the finality of the fundraising is a promise or expectation, not a guarantee. But a key feature is they often go beyond the VC circle to bring in a broader group of investors. In the past, the job of an IPO was to make this transition from private to public market shareholders. Now FPOs start the process earlier, though with some of the same beat-the-rush allure.

3. What’s in it for investors?

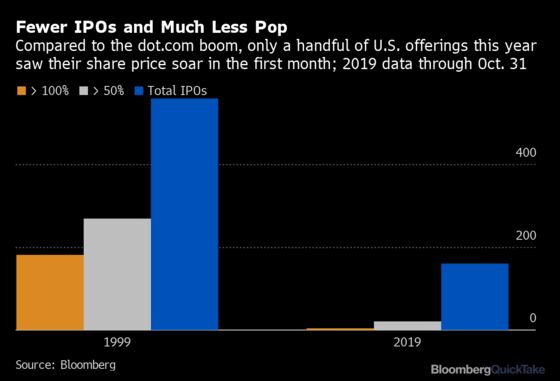

Getting in on an FPO can make it easier for them to amass a large stake in a company than if they wait for the IPO. During the IPO process, a company sells a limited pool of stock, with investment banks deciding how it’s apportioned. Some FPO rounds can become so big that the investors that normally would have tried to get in on an IPO allocation stay on the sidelines because they already own stakes -- a factor that’s been cited in the lackluster responses when Uber Technologies Inc. and Lyft Inc. launched their IPOs. Peloton Interactive Inc. and SmileDirectClub Inc. also won big backers in private transactions, only to see their shares drop after public offerings. Overall, IPOs have lost a lot of their luster as instant cash machines: In the first 10 months of this year, only 13% of new offerings in the U.S. saw their share price rise by 50% or more in the first 30 days. In 1999, during the dot-com boom, almost half of U.S. IPOs met or exceeded that performance.

4. Who buys in?

Hedge funds, sovereign wealth funds and family offices are all among FPO investors. Engineers and executives in the tech industry have also been pooling their money into special purpose vehicles that buy stock from startup insiders. These opportunities even attract mutual fund companies that traditionally have focused on public markets, like Fidelity Investments Co. and T. Rowe Price Group Inc. So far this year, 27% of VC rounds that raised more than $100 million had at least one such “crossover” investor that normally deals in public markets. That’s up from 13% in 2017, according to Silicon Valley Bank.

5. Are there any downsides?

Private investments don’t always live up to their original promise. When an IPO planned by WeWork collapsed, the steep fall in the company’s fortunes showed the perils of private markets, where valuations can soar only to fall into a downward spiral when faced with the scrutiny of public markets. Airbnb Inc. has also raised billions of dollars, including from crossover investors, as a private company. But its private valuation of about $31 billion has barely budged since 2016, even as the company worked on plans to publicly trade its shares next year.

The Reference Shelf

- An overview of Final Public Offerings.

- The man who brought mutual funds into private markets.

- How special purpose vehicles can siphon money from IPOs.

- A look back to 2015 and the private-market rise of tech “unicorns.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Annie Massa in New York at amassa12@bloomberg.net;Alistair Barr in San Francisco at abarr18@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Alan Mirabella at amirabella@bloomberg.net, John O'Neil, Michael Hytha

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.